The Stairs of Weehawken, Part 1

WHERE: Weehawken, New Jersey

START: Port Imperial station (Hudson-Bergen Light Rail), fully accessible

FINISH: Boulevard East and Hudson Place, Weehawken, then NJ Transit Bus #128 to Port Authority Bus Terminal, Manhattan

DISTANCE: 0.5 mile (0.8 kilometer)

Photographs by Michael Cairl except as noted. Map courtesy Google Maps.

Map of this walk, reading from top to bottom.

Directly across the Hudson River from midtown Manhattan, Weehawken, New Jersey is best known for two things: the duel in 1804 between Alexander Hamilton, the first U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, and Vice-President Aaron Burr, and the western approach to the Lincoln Tunnel. Somehow I found out that Weehawken has a lot of stairs, so I went to see for myself and do some stair climbing. There are more stairs than I imagined, so after going up two stair towers with a total of 368 steps I stopped, choosing to do the rest another day.

The main part of Weehawken is up a very steep cliff from the flat lands on the riverfront. It was on these flat lands that the Burr-Hamilton duel took place. Hamilton, mortally wounded, was rowed back to New York to die. For over a century from the mid-1800s the lower part of town was taken up largely by passenger and freight railroad terminals, chief among them the West Shore Division of the New York Central. The image below shows what this looked like viewed from the top of the hill, at the intersection of Pershing Road and Boulevard East, around 1940.

Image courtesy pinterest.com.

The gabled building in the center of the image still exists; it is now a Mexican restaurant. And there is still a filling station where the Esso sign is.

Freight trains once transferred their cars to barges to be moved across the river and around the harbor. Passengers did the same, taking ferries to the foot of West 42 Street in Manhattan. The railroad terminals are gone, replaced by the Lincoln Harbor and Port Imperial mixed-use developments, parks, and the NY Waterway ferries to Manhattan. New Jersey Transit’s Hudson-Bergen Light Rail serves this area from Hoboken and points south. North of Port Imperial station, where this walk began, the light rail uses a portion of the West Shore right-of-way, including a tunnel under Bergen Hill that includes the only underground station on the system.

At the Port Imperial station there are stairs and a clean, working elevator to an overpass leading to Port Imperial on the east and a stair tower to Pershing Road on the west. The stairs are in excellent condition but the climb is arduous: a first flight of 11 steps followed by 11 flights of 12 steps each, for a total of 143 steps.

Port Imperial stairs, looking up.

Port Imperial stairs, looking down from Pershing Road.

From the top of the stairs I went downhill on Pershing Road’s narrow sidewalk to another stair tower, the Liberty Stairs. I was not prepared for what a climb this would be, and took a short break at each landing. But I made it up 225 steps to beautiful Boulevard East. These stairs are also in excellent condition, although a section of handrail is missing on one of the upper flights. Nice job, Township of Weehawken!

The Liberty Stairs, looking up from Pershing Road.

I biked along Boulevard East twice in the 1990s as part of a route from the George Washington Bridge to Hoboken and Bayonne. Then as now, the view of Manhattan was amazing and the houses with that view are enviable. Facing the river is lovely Hamilton Park, the centerpiece of which is Weehawken’s World War I memorial, flanked by smaller memorials to the Weehawken residents who died in World War II, the “police action” in Korea, and the Vietnam war.

Homes on Boulevard East across from Hamilton Park.

World War I monument.

The Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge is visible in the distance.

Historical marker on Boulevard East describing a long-gone amusement park. Interestingly, a short distance north of here was Palisades Amusement Park, also at the top of the cliff, that ran from 1894 to 1971.

I picked a beautiful day for this walk. There is much more to see around here and more stairs to climb. Today, these two stair towers were enough. I’ll be back to Weehawken for more.

Allow me a sidebar on those new super-tall towers visible in Manhattan. I’ll leave aside my distaste for them (alright, they’re disgusting). When I’m not full of bile about them, they call to mind a town in Tuscany, San Gimignano, where in the Middle Ages the leading people in town competed with each other to build tall towers in a long-running game of one-upsmanship. Most of the towers are long gone but on a visit there in 1991 I got to climb to the top of one. The view of the town and the green countryside was worth the climb. I doubt the towers on “Billionaires’ Row” will last nearly that long.

By the Sea, By the Beautiful Sea

WHERE: The Rockaway Peninsula, Queens

START: Beach 67 Street subway station (A train), fully accessible

FINISH: Rockaway Park - Beach 116 Street subway station (S train), fully accessible

DISTANCE: 2.75 miles (4.4 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl. Map courtesy footpathmap.com.

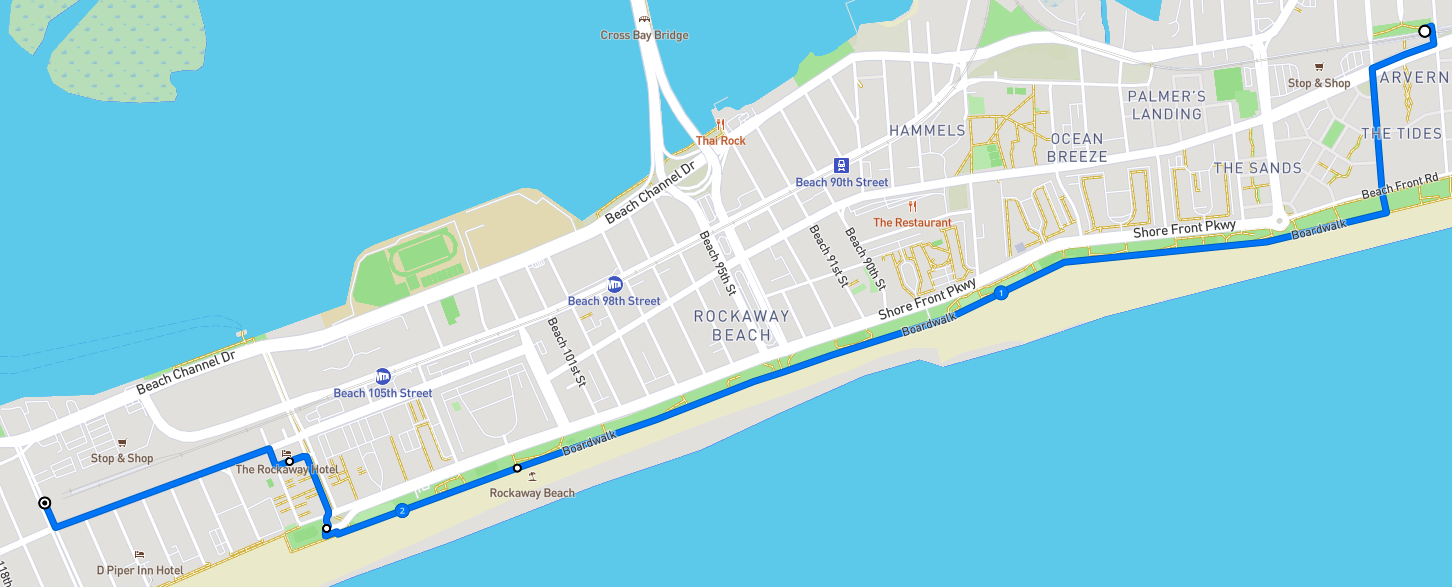

Map of this walk, reading from right to left.

The Rockaway Peninsula is a narrow spit of land, a barrier between the Atlantic Ocean and Jamaica Bay. If you’ve looked out the window of an aircraft arriving at or departing from JFK Airport, you’ve seen it. The different communities on the peninsula are known collectively as the Rockaways.

A part of New York City, the Rockaways have tidy, suburban-style houses, beach bungalows, apartment blocks facing the beach, public housing projects, and apartments built since Superstorm Sandy in 2012. Generations have lived in the Rockaways and called it home.

The Long Island Rail Road built a branch across Jamaica Bay to the Rockaways in the late 19th century. New York City took over this line after the LIRR abandoned it in 1950, rebuilt it, and converted it to subway service. It is not uncommon to see someone with a surf board on a train out to the Rockaways. It’s a long subway ride from the Rockaways to Manhattan, but people make that trip every day.

This walk began at the elevated Beach 67 Street - Arverne subway station, recently refurbished and made fully accessible. The accessibility project was unexpectedly difficult but overall it’s a good job. At street level, there is a surf shop.

From the late 19th century until World War II, Arverne was a community of beach bungalows. It was largely abandoned in the 1950s and 1960s. Various redevelopment schemes came to nothing, but starting in the early 2000s new housing took root. The Rockaways were hard hit by Superstorm Sandy but the area has been rebuilt, including the boardwalk that was most of this walk. It would be more appropriate to call it a promenade, as Sandy destroyed the old wooden boardwalk, long segments of which were so deteriorated as to be unusable.

Starting at the subway station, we made the short walk to the boardwalk, past someone renting surf boards from a van. The new boardwalk is a delight for riding a bike, as I discovered after it opened in 2016, but I did this walk with a runner who said the concrete surface isn’t good for running.

At Beach 91 Street there is a memorial to a local lifeguard, teacher, surfer, and fire fighter, Richie Allen (1970 - 2001).

The plaque on the wooden post to the left of the lamppost reads:

Firefighter Richie Allen

SON, BROTHER, UNCLE, FRIEND, HERO, ANGEL

The beach was Richie’s heaven on earth. He was a lifeguard and a talented surfer who loved the rush of catching a wave. In an amateur surfing film written by Richie, he states “Beach 91st Street is the best surfing spot in NYC. By some local surfers, it’s known as the arena where reputations are built and destroyed. Swells that have crashed on this beach have made this place legendary.”

On September 11, 2001, Richie heroically gave his life as a NYC firefighter.

In his memory, enjoy this beach, surf its water and live life to the fullest as that was and always will be … Richie Allen’s Way.

A Hui Huo Ohana

On these walks I’ve met many people. Richie seems one of those people I wish I had met. For more about him go to https://voicescenter.org/living-memorial/victim/richard-dennis-allen-richie.

From there we went to lunch at Happy Jack’s Burger Bar across from The Rockaway Hotel. This is a delightful place for locals. I’ll be back.

The rest of the walk was unremarkable except for this place whose name was so odd we had to cross the street to have a look. Sure enough, it’s a pour-your-own-beer joint. One could do that at home.

Cherry Blossoms in the Brick City

WHERE: Branch Brook Park, Newark, New Jersey

START: Branch Brook Park station (Newark Light Rail), fully accessible

FINISH: Bloomfield Avenue station (Newark Light Rail), fully accessible

DISTANCE: 1.4 miles

Photographs by Michael Cairl. Map courtesy Google Maps.

Until a couple of days ago I had no idea there were thousands of cherry trees in Newark, New Jersey, mostly in Branch Brook Park. I had biked along Bloomfield Avenue past this park but had never been in the park.

When I lived in Washington, D.C., cherry blossom time was a very big deal. Helen Taft, wife of the 27th President, William Howard Taft, spearheaded the planting of cherry trees along the Tidal Basin. Many thousands of people go down to the Tidal Basin to see the cherry blossoms every year, These are delicate flowers and will not survive wind and rain. In the seven years I lived in Washington, only once did the blossoms last long enough for me to photograph them. Knowing full well how fragile these blossoms are, and knowing I could get to Branch Brook Park on the Newark Light Rail, I had no time to lose and had to see them for myself.

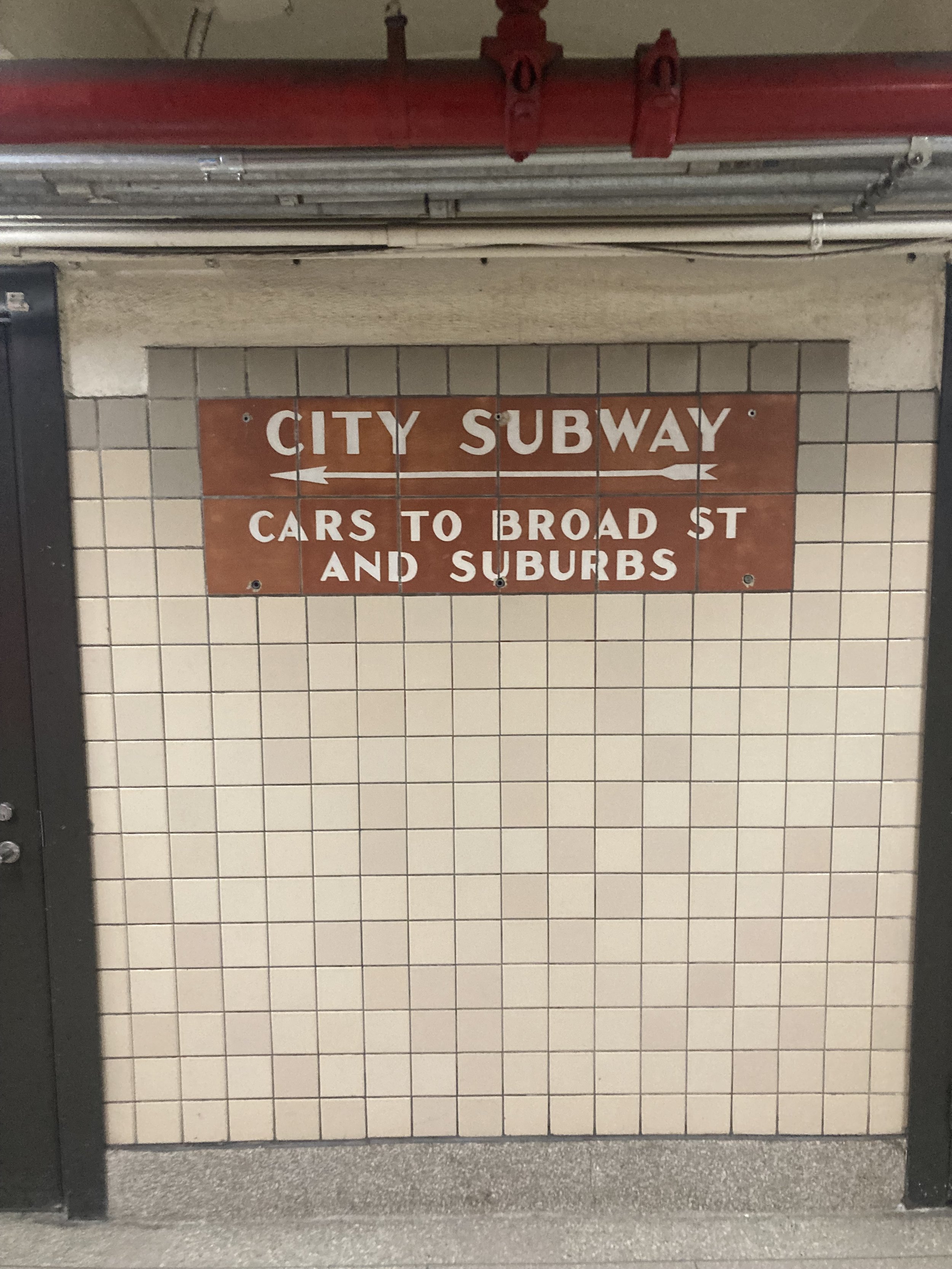

Newark Light Rail used to be called the Newark City Subway. Before it was converted to a light rail line in the early 2000s it was served by streetcars that converged from various points into a tunnel underneath Raymond Boulevard in downtown Newark, terminating at Penn Station. The one remaining line, from Penn Station to Branch Brook Park, had been built in the 1930s partly in the bed of the Morris Canal, which had been abandoned. New Jersey Transit has not obliterated the 1930s signs or artwork. A nice presentation on the artwork can be found at https://sites.google.com/site/historictileinstallationsn/nj_newark--wpa-morris-canal-murals. A detailed history of the City Subway/Light Rail, with a lot of images, can be found at https://www.nycsubway.org/wiki/Newark,_New_Jersey_Light_Rail/City_Subway. Here’s one of the mosaics at Penn Station, evoking the Morris Canal and Newark’s industry, and a directional sign in Penn Station. “Cars” refers to streetcars.

I worked on the extension of the Light Rail from Penn Station to Broad Street Station in 2005 - 2006.

From the Branch Brook Park station, I walked up the ramp to Heller Parkway and the park. Just past the intersection of Branch Brook Park Drive is a monument to tennis great Althea Gibson (1927 -2003), who lived for years in nearby East Orange. In 1956, she became the first African American to win a Grand Slam event (the French Championships). The following year she won both Wimbledon and the US Nationals (precursor of the US Open), then won both again in 1958 and was voted Female Athlete of the Year by the Associated Press in both years. In all, she won 11 Grand Slam tournaments: five singles titles, five doubles titles, and one mixed doubles title.

Althea Gibson monument.

In 1898 the Essex County Park Commission hired the Olmsted Brothers firm; John Charles Olmsted and Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. were Frederick Law Olmsted Sr.'s nephew/stepson and son. While their work continued that naturalistic style of landscape design championed by their father, in Branch Brook Park they were required to incorporate the elements of Bogart and Barrett's plan that had already been constructed. This led to the Olmsted firm's design concept consisting of three divisions: the Southern, from Sussex Avenue to Park Avenue, incorporating elaborate "gardenesque" elements; the Middle, from Park Avenue to Bloomfield Avenue, which would be a transitional zone, mixing the exotic with the indigenous; and, as the culmination, the Northern Division, the largest and most naturalistic area of the park.

In 1928 Caroline Bamberger Fuld, of the family that owned Bamberger’s department store in Newark, donated 2,000 Japanese flowering cherry trees to a display in Newark that would rival that in Washington, D.C. Eventually the collection would grow to more than 3,000 trees. Had I decided to walk to the light rail at Park Avenue, not Bloomfield Avenue, I’d have walked past many more cherry trees than I did. Oh well. I saw plenty from the train between Bloomfield Avenue and Park Avenue.

Branch Brook Park is just beautiful. The footpath paralleling the park drive is paved with a bituminous material that has a bit of “give” to it and was a pleasure to walk on. Except for a few spots that need to be repaired, the footpath is in very good condition. The path up to Bloomfield Avenue does need to be rebuilt, though. The park drive was closed to cars and there was a bicycle race going on.

Along the footpath is a memorial to a Newark police officer killed in the line of duty in 1997, Dewey J. Sherbo III.

This park certainly merits a return visit and a longer walk, ending with a good meal at Hobby’s Delicatessen downtown or one of the many good Spanish and Portuguese restaurants in the Ironbound neighborhood, east of Penn Station. Newark has “good bones” and is blessed with excellent transportation and cultural institutions.

Route of this walk, reading from top to bottom.

Dumplings and Such (Manhattan)

WHERE: The Lower East Side of Manhattan, mostly

START: The corner of Fulton and William Streets (Fulton Street subway stations: 2, 3, 4, 5, A, C, J trains, fully accessible)

FINISH: Delancey and Essex Streets (F, J, M trains and M14A SBS and B39 buses)

DISTANCE: 1.6 miles (2.5 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl except as noted. Map courtesy footpathmap.com.

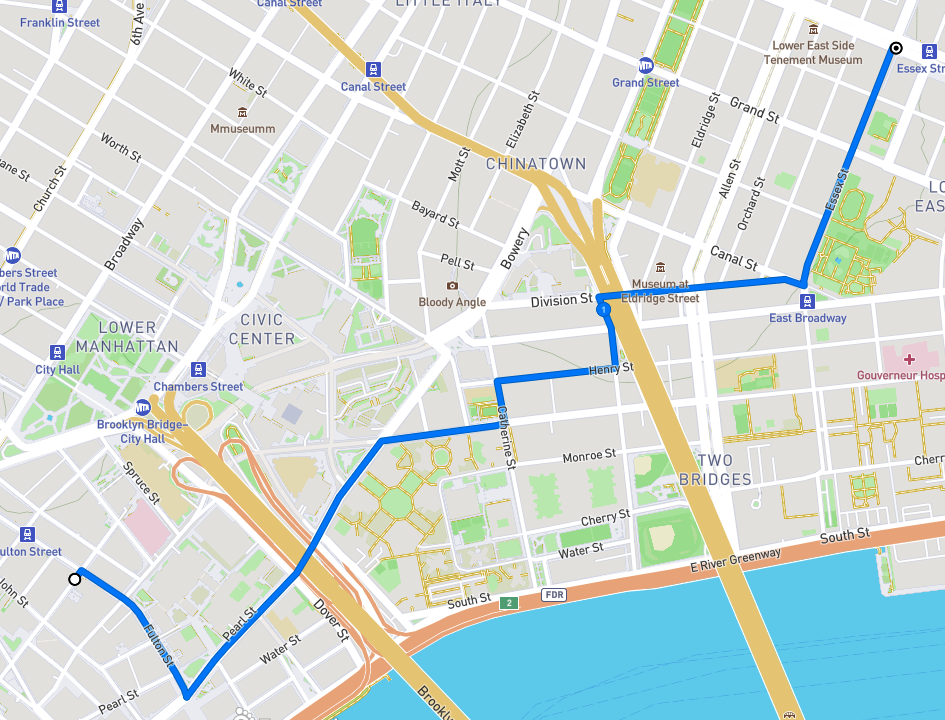

Route of this walk, reading from left to right.

I had advertised this walk on the blog as “Chinatown Dumpling Crawl.” Nobody else showed up and I have rescheduled it; see the Coming Events page. Still, it was a nice Saturday before Easter, so I decided to do part of the planned walk. A proper food crawl or pub crawl has to be done with others.

Coming out from the subway at Fulton and William Streets, I could not help but notice how the vista looking west was dominated by 1 World Trade Center.

I walked east on Fulton Street through an area that has seen a lot of change since World War II, admittedly a long time ago. The South Ferry branch of the Second and Third Avenue elevated lines used to run above Pearl Street, which crosses Fulton. Here is a “then and now” look south on Pearl from Fulton, the first image from 1936 by Berenice Abbott, courtesy The Museum of the City of New York via urbanarchive.org, and the second taken on this walk.

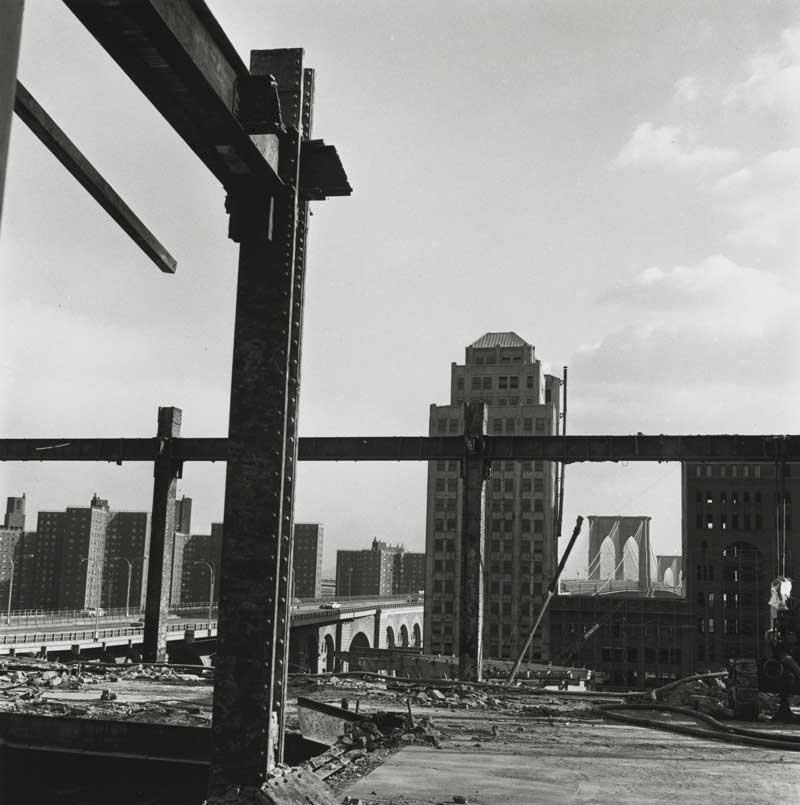

The construction of the World Trade Center started in the mid-1960s and changed Manhattan south of Canal Street profoundly. Many blocks of old commercial buildings were razed to make way for the World Trade Center and, along this walk, the Southbridge Towers apartment complex. Photographer Danny Lyon documented this in his great book The Destruction of Lower Manhattan (New York, powerHouse Books, 2005). This was the subject of an exhibit at the Museum of the City of New York in 2005. One of his images from the area on this walk is below.

A bit farther on is Water Street and the entrance to the South Street Seaport, to which I might return on a future walk. I walked this way mainly to see the memorial to the people who went down with the Titanic in 1912. The plaque shown in the second image tells the story of the Titanic Memorial Lighthouse.

Before European settlement the shoreline of the East River was where Water Street is now. Starting in the 1600s the shoreline was extended with landfill; now Water Street is two blocks from the river.

Just north of Fulton Street, Water Street and Pearl Street merge and continue underneath the Brooklyn Bridge. From Pearl Street I turned right onto Madison Street, past the Alfred E. Smith Houses, a large public housing complex built after World War II. Madison Street was named for the fourth President of the United States, James Madison. The history of street names that follows is taken from that invaluable resource, The Street Book, by Henry Moscow (New York, Hagstrom Company, 1978). Until 1826, nine years before Madison died, Madison Street was called Bancker Street, but the area had deteriorated and the Bancker family requested their name be removed. I turned left onto Catherine Street which was named for Catherine Rutgers, part of the Dutch gentry in New York. One block on, I turned right onto Henry Street, which was named for Henry Rutgers, who donated two lots to the City for construction of a school, with the stipulation that it had to open by 1811. It opened in 1810.

At 25B Henry Street was my first dumpling stop of the day, Jin Mei Dumpling. It is truly a “hole in the wall” with all transactions handled at the front door. There is a table with two chairs outside. I had sesame pancake and fried pork buns that were excellent and inexpensive. An elderly couple in line ahead of me had come down from the northern Bronx to get a lot of dumplings and such.

Feeling happy and sated, I continued on to Market Street, in the shadow of the Manhattan Bridge, and turned left at the First Chinese Presbyterian Church. This is not traditional Chinatown but it is certainly the heart of modern Chinatown.

The church house at the First Chinese Presbyterian Church.

East Broadway, looking west from Market Street.

Market Street was named for the Catherine Market, a wholesale food market established in 1786 between Catherine Street and Market Street, then known as George Street. Market Street is full of people and markets selling food and stuff.

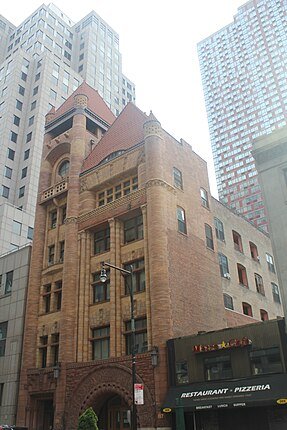

From Market Street I turned right onto Division Street and beneath the Manhattan Bridge. At the corner of Allen Street is a large, oddly shaped brick building with various businesses on the extended street level and a lot of graffiti. This was built in 1900 as an electrical substation for the Manhattan Railway Company, which operated the elevated transit lines in Manhattan. The Second Avenue Elevated ran above Division Street and turned onto Allen Street, right past the substation. Division Street’s name came from it being the boundary between the 18th century farms of James de Lancey and Henry Rutgers. According to The Street Book, “the space occupied by the street was a kind of no-man’s land used for a rope walk, i.e. a place where hemp was twisted into rope.”

Manhattan Railway Company Substation No. 1.

Continuing on Division Street, I walked through an area that from the late 19th century was mostly Jewish and is now a jumble of ages and ethnicities, restaurants with outside seating and more than one tattoo parlor. Here are some random images.

I turned left onto Essex Street and stopped in front of North Dumpling. I’ll eat there on the dumpling crawl but I was still full from my feeding on Henry Street.

North Dumpling on Essex Street.

This short walk packed in a lot of interesting things to see and good food to eat. I saw a tour guide on Essex Street telling his charges about the area, I chatted a bit with a charter bus driver from Trois-Rivières, Québec who was fretting about how to navigate his bus through the narrow streets, and I saw a lot of people out and about, happy perhaps for yet another Spring.

Upper Grand Concourse to Kingsbridge (Bronx)

WHERE: The northern part of the Grand Concourse and Mosholu Parkway, the southern fringe of Van Cortlandt Park, and Kingsbridge, Bronx

START: Kingsbridge Road subway station (D train), fully accessible

FINISH: 238 Street subway station (1 train)

DISTANCE: 3.1 miles (5 kilometers)

Photograph credits as noted. Map courtesy footpathapp.com.

Route of this walk, reading counterclockwise.

This walk was inspired by historic preservationist Thomas Rinaldi and his photographs of buildings on and near the upper Grand Concourse. This was built up mostly after World War I, after the elevated subway opened on nearby Jerome Avenue (today’s 4 train). The pace of construction accelerated after the Concourse subway (today’s D train) opened in 1933. The upper Grand Concourse offers a pleasing vista of mostly mid-rise apartment buildings of more or less uniform height. The building facades differ in their details, giving the observant passerby a lot to enjoy and think about.

The walk started at the Kingsbridge Road subway station. Unusually, one has to go down from the platforms to the fare control area. Kingsbridge Road passes underneath the Grand Concourse. The subway entrance abuts what was a streetcar stop when the station opened. From the fare control area, stairs and an elevator go up to the street.

At the intersection is a park and Poe Cottage, the onetime country home of Edgar Allan Poe. For some history of the house see the post entitled “A Raven, A Ram, A Two-Headed Eagle, and Prosciutto Bread” on “The Stair Streets of New York City” page.

In front of Poe Cottage: Mark, Yours Truly, Dan, Michael, Paul, Nathaniel. Photograph by a kind passerby.

Walking north on the Concourse we saw a lot of attractive apartment buildings.

Photograph by Michael Cairl.

Who was Luke Nee? Someone I wish I had met. The New York Times printed short biographies of people who died in the attacks on September 11, 2001.

LUKE NEE Bronx in His Blood

As a boy, Luke Nee played all the games that a Bronx sidewalk offered to kids on Minerva Place, just off the Grand Concourse: stickball, of course, and off-the-point and street hockey.

Right out of Cardinal Hayes High School, he answered a help-wanted advertisement for people with math skills and landed a job at Drexel Burnham Lambert. Before long, a half-dozen guys from the block followed. It was a small world, he would say, but he would not want to paint it.

At Drexel, he met Irene Lavelle, and they were married Sept. 11, 1982. After he had shifted to Cantor Fitzgerald, he would chew through a couple of novels a week on the train ride from Stony Point, N.Y., said his brother, John Nee. His Bronx roots showed: he shared a ticket plan for Friday night Yankee games with boyhood friends from St. Philip Neri School.

Mr. Nee, 44, made the simple pleasures glow. ''He treasured Irene and loved bringing their son, Patrick, to ballgames,'' said his brother. On summer weekends, he, Irene and Patrick would jump in the car, pick up a few relatives and head for the beach. And on Sept. 11, he made a final call of farewell and love to his family.

''Luke was just a friendly, kind, peaceful, and unaffected guy,'' said Mr. Nee. ''Meatball heroes, watch a movie with Patrick -- that was a Saturday night.''

Photograph by Mark Foggin.

Photograph by Michael Cairl.

At the corner of Bedford Park Boulevard we stopped to admire the architectural details of 2939 Grand Concourse, one of which is pictured below. Nathaniel in our group asked what I saw in this detail. I responded that I saw that here was fine embellishment of an apartment building in the Bronx, not on Park Avenue, so my appreciation was sociological as well as aesthetic.

Photograph by Michael Cairl.

On Bedford Park Boulevard, just west of the Concourse, is an odd mishmash of old and new buildings.

Photograph by Daniel Murphy.

Here and there one could see houses and other buildings that had not been replaced by apartment houses. The cornerstone of St. Philip Neri Roman Catholic Church is dated 1899 and was something more than a humble country church in what was then a thinly populated area. This is how the church looked in 1928; it is little changed now.

Photograph courtesy The New York Public Library via urbanarchive.org.

From the Grand Concourse we turned east on East 205 Street. At the corner of Mosholu Parkway and Lisbon Place we saw a handsome modern apartment building from 2012 that one in our group said would not have been out of place in Southern California or Miami.

170 East Mosholu Parkway. Photograph by Michael Cairl.

From Mosholu Parkway we turned west on East 206 Street to St. George’s Crescent and saw some beautiful apartment buildings, one in particular, 185 St. George’s Crescent, built in 1938. This is just stunning and was built for the middle class.

185 St. George’s Crescent (the light-colored building). Photograph by Michael Cairl.

Photograph by Michael Cairl.

Photograph by Michael Cairl.

Photograph by Michael Cairl.

St. George’s Crescent turns into Van Cortlandt Avenue, on the north side of which are the Pickwick Arms apartments (1925), a grand courtyard apartment building in a sort-of-Tudor style.

Pickwick Arms, 1927, seen from the intersection of Mosholu Parkway (left) and Grand Concourse. Photograph courtesy The New York Public Library via urbanarchive.org.

Interior courtyard, Pickwick Arms, 1928. Photograph courtesy The New York Public Library via urbanarchive.org.

From St. George’s Crescent we turned east on Van Cortlandt Avenue, then north on Mosholu Parkway, on a footpath that is in only fair condition. We passed underneath Jerome Avenue and the grand Mosholu Parkway subway station, passed DeWitt Clinton High School, and turned left onto Sedgwick Avenue, then right onto Dickinson Avenue and left onto Van Cortlandt Park South.

Across from Van Cortlandt Park South, on the south side of Van Cortlandt Park South, are the Amalgamated Houses. This is the oldest limited equity housing cooperative in the United States, sponsored by the Amalgamated Clothing Workers Union starting in the 1920s. The older buildings have some beautiful details.

Photograph by Mark Foggin.

Photograph by Mark Foggin.

Photograph by Mark Foggin.

Photograph by Michael Cairl.

Just past Gale Place we descended the Van Cortlandt Park South stairs (81 steps), which I described in my post “3 South of Van Cortlandt Park” on “The Stair Streets of New York City” page. From there we went south on Bailey Avenue and west on West 238 Street to lunch at the Kingsbridge Social Club, which contrary to its name is not a private club but a place for pizza, pasta, and salad. The mirror in the washroom is a playful take on one of Kingsbridge Social’s specialties.

Photograph by Mark Foggin.

Lastly, some neat old signage seen along the way, described by photographer Mark Foggin as “Elegance in hyper-local advertising.”

This was a fine walk with a good group of friends, good exercise with plenty of interesting things to look at. Walks like this are my oxygen and the definition of fun and physical therapy.

At lunch at Kingsbridge Social Club, left to right Paul, Michael, Yours Truly, Joe, Mark, Dan. Photograph by one of the staff at Kingsbridge Social.

Williamsburg Bridge (Manhattan to Brooklyn)

WHERE: The Williamsburg Bridge

START: Delancey Street - Essex Street subway station (F, J, M trains) and M14A SBS bus

FINISH: Marcy Avenue subway station (J, M trains), fully accessible, and B24, B44, B44 SBS, B46, B46 SBS, B62, Q58, Q59 buses

DISTANCE: 1.8 miles (2.9 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl. Videos courtesy the Library of Congress. Map courtesy footpathmap.com.

Route of this walk, reading from left to right.

The Williamsburg Bridge is the last of the East River bridges that I’ve walked. I’ve biked over the bridge a few times and crossed by car and by subway, but this was the first time I had crossed it on foot. It is arguably the ugly duckling of the East River bridges, but it has a fascinating history and is oddly appealing.

This walk started at the intersection of Delancey Street and Essex Street on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. The subway station here is not accessible but there are escalators from the lower level platforms (F train) directly up to the street. Going down to any part of the station, it’s all stairs. Underground, just south of the upper level platforms (J and M trains), is the former streetcar terminal for the bridge, unused since 1948. In recent years there was a proposal to turn that area into an underground park, a sort of subterranean High Line, but nothing has come of that.

This area is seeing a lot of change. The City-owned, 1930s-era Essex Street Retail Market is shuttered and derelict. Across Delancey Street is the gleaming new Essex Market high-rise, to which the vendors from the old market and others have moved. The Essex Street Market and others like it were built by the City to get food vendors off the street and into modern, sanitary facilities. Six remain; read about them at https://publicmarkets.nyc/our-markets. In much the same spirit, but over a much longer time, the City’s wholesale food markets were moved to Hunts Point in the Bronx. My friends at Turnstile Tours lead occasional visits to these markets; check them out at https://turnstiletours.com/.

The block of Delancey Street east of Essex Street used to be home to Ratner’s, a kosher dairy restaurant (yes to fish, no to other meat) renowned for their blintzes. On the other side of Delancey, in a row of small shops, was a hat shop where I once bought a fedora. All gone in favor of a new mixed-use development called Essex Crossing.

Menu from Ratner’s, 1953.

The Williamsburg Bridge was the second bridge to be built spanning the East River and replaced a ferry that ran just to the north, from Grand Street in Manhattan to Grand Street in Brooklyn. It was begun in 1896 and took seven years to build. The chief engineer was a son of Brooklyn with a very old Brooklyn Dutch name: Leffert Lefferts Buck.

Plaque at the Manhattan end of the bridge.

The bridge was designed to carry heavy foot traffic, streetcars, and Brooklyn elevated trains. It opened to great fanfare in 1903. Part of the opening day procession was captured on film.

Once the bridge opened, people started moving out of the slums of the Lower East Side to new housing in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. In Yiddish it was called the Naiye Brick, or New Bridge. It was also known as “the Jews’ Highway.” People who moved to Williamsburg walked over the bridge to work. Brooklyn elevated trains started operating over the bridge to a temporary terminal at Essex Street in 1908, and by 1918 this was upgraded to subway service.

The bridge was plagued by years of not being properly maintained and was closed in 1988 for emergency repairs after one of the suspension cables snapped. That wasn’t all: according to The New York Times on 17 April 1988,

The main cause of corrosion on the Williamsburg Bridge is salt, which is placed on the roadway to melt snow or is sprayed up from the East River. A continuing flow of salt water turns structural steel members into batteries that begin to corrode. This so-called corrosion cell activity has been particularly damaging to the steel floor beams in the roadway of the bridge. City engineers said at least 30 of the bridge's floor beams were severely corroded.

The same article noted

Perhaps the most severe problem with the bridge is the corroding of the four large cables. The cables, which consist of more than 7,000 different wires, are in disrepair because they were not galvanized when the bridge was built. The problems began to appear as early as 1910, engineers said. Several early efforts to remedy the corrosion failed.

The bridge was built with two foot paths but by the first time I biked across it, around 1990, only one was open and it was in poor condition. There was some thought given to demolishing and replacing the bridge. Extensive rehabilitation began in 1992 and proceeded in stages for the next ten years. Separate bicycle and pedestrian paths were installed, except for a combined path at the Manhattan end, and the new paths comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act. Part of the elevated subway structure at the Brooklyn end was replaced by a precast concrete structure.

The entrance to the bike and pedestrian path at the Manhattan end has a suitably grand portal that recalls some of the bridge’s original aesthetic elements.

At the vanishing point of the footpath in the above image, it divides into two, with foot traffic on the right (south) side and bicycles on the north side.

North (Manhattan-bound) roadway, bicycle path, subway tracks, south (Brooklyn-bound) roadway, pedestrian path.

The first time I biked over the bridge, I was in awe of how much steel there was in the structure. It is as though every steel mill in America had been pressed into service for the construction of this bridge.

All this steel! And graffiti - some of it clever, some boring, some snarkily vacuous - covers the pedestrian path from beginning to end.

From the Brooklyn anchorage to the end of the pedestrian path the descent is slightly steep and I walked with some care. From the end of the path turn right (Bedford Avenue), then cross and turn left on Broadway, continuing to the subway at Marcy Avenue or to one of the many bus lines serving the area.

The Williamsburg Bridge is very well used by walkers, runners, and cyclists. At either end of the bridge is an area undergoing great change: demographic on both sides, de-industrialization and residential redevelopment of the waterfront in Brooklyn. This was an easy and very interesting walk.

East Midtown Greenway (Manhattan)

WHERE: The East Midtown Greenway on the east side of Manhattan

START: Lexington Avenue - 63 Street subway station ,(F and Q trains), fully accessible

FINISH: Lexington Avenue - 53 Street subway station (E and M trains), linked to the 51 Street subway station (6 train); both stations are fully accessible

DISTANCE: 1.7 miles (2.7 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl. Map courtesy Google Maps.

Route of this walk, reading from top to bottom.

Happy New Year! The pedestrian/bike path on the east side of Manhattan, a discontinuous mess twenty years ago, is being made continuous and accessible, slowly. New York City recently completed a segment on pilings in the East River, outboard of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Drive, from East 54 Street to East 60 Street. I took advantage of a quiet New Year’s Day for a fully accessible walk to and along this new segment, called the East Midtown Greenway.

The walk started at the Lexington Avenue - 63 Street subway station, using the elevators at the 3 Avenue end of the station to reach the street. From there I walked east on East 63 Street to the pedestrian suspension bridge spanning the FDR Drive to the ramp down to the waterfront promenade. At the bottom of the ramp turn to the left to walk uptown (see the post on this page entitled “John Finley Walk, Carl Schurz Park, Bobby Wagner Walk”) or straight ahead toward the East Midtown Greenway.

The East Midtown Greenway is not long but it is magnificent. It has completely separate pedestrian and bike paths. Both are wide and the pedestrian path has plenty of places to sit.

North end of the East Midtown Grenway.

The views are worth the effort to get there.

To the right of the United Nations Secretariat building, one can see One World Trade Center in the distance.

Leading to East 54 Street, an arch bridge over the FDR Drive is part of a fully accessible exit.

From the ramp off the arch bridge, cross Sutton Place South and walk west on East 54 Street. Between 1 Avenue and 2 Avenue I found this grand structure from a time when municipal architecture was good and solid, the Constance Baker Motley Recreation Center.

From the NYC Parks website: “Located in the heart of midtown, the 54th Street Recreation Center has been a community staple for years. It is named in honor of Constance Baker Motley. Motley, born in 1921, was the first African American woman to become a federal judge. She was a leading jurist and legal advocate during the Civil Rights movement, and the first Black woman to serve as Manhattan Borough President.”

I continued to the Lexington Avenue - 53 Street subway station. The elevator from the street is at Lexington Avenue and East 52 Street and serves the mezzanine connecting this station and the 51 Street station.

This was an easy, enjoyable, fully accessible walk. If you’re ambitious you could do it in reverse, starting at the Lexington Avenue - 53 Street station, and at the 63 Street pedestrian bridge keep walking north on the promenade, following the path described in my post “John Finley Walk, Carl Schurz Park, Bobby Wagner Walk.”

Addisleigh Park (Queens)

WHERE: The Addisleigh Park Historic District in the St. Albans neighborhood of Queens

START/FINISH: St. Albans station (Long Island Rail Road), also Q4 bus

DISTANCE: 1.8 miles (2.9 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl. Map courtesy Google Maps.

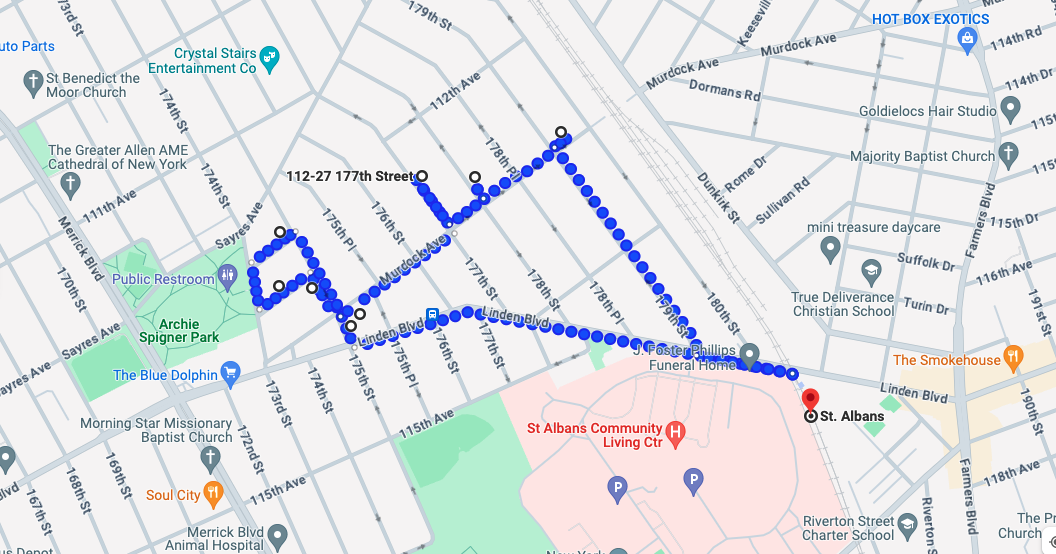

Route of this walk, reading clockwise from the right.

Until recently I did not know about Addisleigh Park in Queens, but after a piece on the radio about the area I did some research and decided this would be worth the trip and the walk. I was not disappointed. Addisleigh Park is the African-American “Gold Coast” of New York City, perhaps more so than Sugar Hill in Manhattan. Many African-Americans who were prominent in athletics, entertainment, and letters moved here, as well as one outlier.

St. Albans is in southeast Queens. Before World War I this area was semi-rural, but since the 1910s it has been semi-suburban and easily accessible to Manhattan by the Long Island Rail Road. It is a quiet, low-traffic, low-rise neighborhood of detached houses. The main street in the area, Linden Boulevard, has a small commercial zone near the train station. Before World War II the U.S. Navy moved the Naval Hospital from the Brooklyn Navy Yard to a campus in St. Albans. That campus now houses a primary health care facility of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

At the Untapped Cities website there is an excellent look at Addisleigh Park. Take the time to read it at https://untappedcities.com/2020/06/23/explore-queens-addisleigh-park-the-african-american-gold-coast-of-ny/. But I shall quote the following by way of introduction.

The area was mainly developed in the 1920s and 1930s, developed by the Burfey Realty Company, and originally the area attracted famous golfers since Addisleigh Park was built close to the St. Albans Golf Course. Drawn by the golf course, Babe Ruth also had a home in the area at 114-07 175th Street, which was primarily settled by white families at the time. The area was initially created as a segregated area for white people, yet by the 1940s, this policy was reversed and many African-American families began to move into the area. Addisleigh Park contains around 650 homes in English Tudor and neo-Colonial Revival style, many built between 1910 and 1930.

According to Laurie Gwen Shapiro, author of The Stowaway, who recently went to the neighborhood on research for her next book and offered us the pictures, “I met many residents who asked me why I was walking around and after a few words of explanation everyone I spoke to was thrilled I was interested in local history and told me other buildings that are not listed – like where Mercer Ellington and Willie Mays and Wild Bill Davis lived. Everyone I met had lived there for over 30 years and said no one ever moves. It is home.”

The walk started at the St. Albans station on the Long Island Rail Road. Underneath the railroad overpass is a mural of some of the people who graced this Gold Coast as residents or visitors.

All West Hempstead Branch trains and some Babylon Branch trains stop here. The station is not wheelchair-accessible, and if you arrive in one of the two westernmost cars you will have to negotiate a large gap between the car and the platform. I’m grateful that a stranger helped me across that gap. If accessibility is a consideration, take the Q4 bus from the fully accessible Jamaica Center subway station (E and J trains); this stops at the St. Albans train station.

Leaving the train station, turn west (left) on Linden Boulevard and continue to 175 Street. Along the way I saw a large house with a corner turret that I had to photograph.

At 175 Street, turn right and cross Linden Boulevard. Just past Linden Boulevard, on the right, is the first house on this walk, 114-07 175 Street. This was once owned by Babe Ruth.

Cross Murdock Avenue. On the left was the next house on the walk, 113-02 175 Street, once home to jazz musician Mercer Ellington, son of Duke Ellington.

Turn left on 113 Avenue. In this block, on the right, is 173-19 113 Avenue, former home of the activist and educator W.E.B. Du Bois and author Shirley Graham.

Turn right on 173 Street and right on Adelaide Road. At the corner of 175 Street is 174-27 Adelaide Road, once home to jazz musician/band leader Count Basie.

Turn right on 175 Street, then cross Murdock Avenue and turn left. The large house on the right, 175-12 Murdock Avenue, once belonged to heavyweight boxer Joe Louis.

Continue on Murdock Avenue and turn left on 177 Street. On this block are 112-40, once home to baseball great Jackie Robinson from 1949 - 1955, and 112-27, where Herbert Mills of the Mills Brothers vocal group lived.

Jackie Robinson house.

Herbert Mills house.

Also on this block is a house I found oddly appealing.

Walk back to Murdock Avenue, turn left, then left on 178 Street. At 112-45 is the former home of the great singer Lena Horne.

Walk back to Murdock Avenue, turn left, walk two clocks to and just past 179 Street. Along the way I saw this street co-named for two pillars of this community, David and Renee Bluford. From the website of the J. Foster Phillips Funeral Home:

Renee has been honored as the recipient of numerous awards from Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity; Jamaica Service Program for Older Adults; Greater Queens Chapter of the Links; NAACP; New York State Association of Black and Puerto Rican Legislators, Inc.; The Guy R. Brewer Democratic Club; New York City Council Member I. Daneek Miller as well as several prestigious awards from local, state, and community organizations.

There is no sidewalk on the left (north) side of Murdock Avenue between 178 Place and 179 Street; either walk in the street or on the sidewalk on the opposite side. The house at 179-07 Murdock Avenue used to be home to Ella Fitzgerald and Ray Brown.

Around the corner, at 114-10 179 Street, is where the great Brooklyn Dodgers catcher Roy Campanella lived.

Turning around (heading south) on 179 Street, walk toward Linden Boulevard. I always enjoy an outdoor Christmas display and think I found the best one in the neighborhood.

Continue to Linden Boulevard and turn left to the train station.

This was an easy walk. There are no hills and most of the sidewalks are in good condition. There is not much car traffic. It’s interesting to think of the house parties that took place here with these prominent people in attendance. Those parties must have been quite the times, especially in an era when Jim Crow was alive and well even in New York. All this, well off the tourist trail.

Onward! Happy New Year!

A Bit of Old Dutch Brooklyn

Route of this walk, reading from top to bottom.

WHERE: The Flatlands and Marine Park neighborhoods of Brooklyn

START: Flatbush Avenue and Avenue K (B41 local bus)

FINISH: Nostrand Avenue and Avenue U (B3, B44, B44 SBS buses)

DISTANCE: 2.79 miles (4.5 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl except as noted. Map courtesy footpathmap.com

It didn’t take long after the Dutch West India Company founded New Amsterdam, in 1624, for new arrivals from Holland to go across what is now called the East River to set up farms and villages in what is now called Brooklyn. Never mind that there were already people living there. There are plenty of reminders of Dutch settlement in Brooklyn, from street names to some old farmhouses to old church congregations. On this walk I visited two: the Flatlands Reformed Church and the Hendrick I. Lott House, and rode the bus past two others: the Lefferts Homestead in Prospect Park and the Flatbush Reformed Church.

This walk was in a part of Brooklyn south of the terminal moraine, a ridge line dating from the last Ice Age that runs the length of Long Island. I have called this Big Sky Brooklyn and, affectionately, Uncool Brooklyn. It is very flat, with only the occasional short hill. The sandy and marshy ground probably reminded early Dutch settlers of home. This part of Brooklyn is comprised of mostly attached houses and two-story commercial buildings, with higher-rise buildings here and there. Nearly all the buildings I walked past were built since World War I.

A few minutes’ walk from the starting point, at Kings Highway and East 40 Street, is the Flatlands Reformed Church. It is one of three Dutch Reformed congregations founded by order of Governor Peter Stuyvesant in 1654. All three congregations still exist, the others being Flatbush Dutch Reformed Church in Flatbush and Old First Reformed Church in Park Slope. The founding pastor of all three, Reverend Theodorus Polhemus, was a ninth great-grandfather of mine. The present Flatlands church is a Greek Revival structure that opened in 1848, replacing a building that opened in 1794.

Flatlands was one of the townships in Kings County, later absorbed into the City of Brooklyn. From the Flatlands church’s website: “Flatlands was recognized as a town in 1788, and the minister was designated as the first Supervisor, perhaps because he was one of the few who had not given his allegiance to the King during the war. By the time the Constitution was ratified in 1789, economic and social necessity had forced amnesty and reconciliation.” This part of Brooklyn remained semi-rural and was not extensively built up until after World War I. Again from the Flatlands church’s website:

In 1838, the Reformed Church was incorporated, and the first parsonage in Flatlands was built, on near the present intersection of Avenue K and Kings Highway, for its first full time pastor. The church reported 100 adults in communion. By 1840, the population of Flatlands had grown to 800. Although slavery had been abolished in New York State in 1827, some former slaves continued to live and work as free laborers.

Kings Highway, which in 1920 was mostly a narrow, unpaved road, was expanded to its present width and paved later in that decade. In August 1776, a large British army landed at Gravesend Bay in southern Brooklyn. One column marched northeast along Kings Highway to Jamaica Pass (near modern Broadway Junction) then west along the Ferry Road (modern Fulton Street) to attack the Continental Army, as commemorated on the historical marker below. The other column marched north to fight in what is now called Prospect Park.

Historical marker just inside the fence of Flatlands Reformed Church, facing Kings Highway.

From the church I walked south along East 40 Street, west on Flatlands Avenue, and south on East 36 Street into the Marine Park neighborhood. There are intervening named streets as well as busy Flatbush Avenue, so the distance from East 40 Street to East 36 Street is not four blocks. (Brooklyn street nomenclature is often confusing.). This is an area I have biked through many times going to or from the Rockaways, but had never walked through. There is little that is remarkable about the streetscape, but I was struck by a pair of huge old trees flanking East 36 Street near Avenue R. One of them is pictured below.

A block or so past the trees is the Hendrick I. Lott House, built in 1720 and enlarged in 1800. From untappedcities.com:

Still standing in its original orientation on its original site, the Hendrick I. Lott House is a rare surviving Dutch-American house in New York City. At its peak, the Lott family owned over 200 acres worth of land, according to the Historic House Trust. Much of their property would be sold off in the 1920s, with the neighborhood later becoming known as Marine Park, but the house remained in the family.

One of the extraordinary finds in this house is a closet believed to have been used to hide runaway slaves, with the house serving as an important stop in South Brooklyn on the Underground Railroad.

From the Friends of the Lott House website:

The exterior of the Lott House represents a traditional Dutch-American vernacular farmhouse. Built c. 1800 by Hendrick I. Lott, it incorporates the 1720 house built by Hendrick’s grandfather, Colonel Johannes H. Lott.

The vernacular style of the house is limited to the exterior; the interior exhibits a much grander style. High ceilings and decorative fireplace mantles and moldings highlight Hendrick’s skill as a professional house carpenter in Manhattan during the last decade of the 18th century. Decorative and architectural features in the house date from the 18th through early 20th centuries. At present, the interior of the house remains unrestored.

The eastern wing of the Lott House is the original 1720 house. It has been theorized that this house was along Kimball’s Road (not to be confused with present-day Kimball Street). Kimball’s Road ran approximately along East 38th Street. It was the 19th-century address of the Lott House, and a driveway turned off of East 38th Street onto the Lott property. It is more likely the 1720 house originally stood where East 36th Street is now.

The Lott House is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is a New York City landmark. New York City purchased the house in 2002 from the estate of Ella Suydam (1896 - 1989), a direct descendant of Hendrick I. Lott and his grandfather Colonel Johannes H. Lott.

This house is rarely open to the public but I will be on the lookout for when it is.

There’s an interesting history of the Lott family and house at https://www.bklynr.com/keeping-house/. I wish I had met Ella Suydam.

From there I walked along Avenue S into Marine Park. Along the way I heard music to my ears: the sound of people who probably have lived in Brooklyn their whole lives. Marine Park has several parts: athletic fields, a public golf course, tidal wetlands with nature trails, and more. I walked along the reconstructed Marine Park Oval to Avenue U. The oval is notable for a line of stately trees.

Leaving the park, I walked west on Avenue U to the end of the walk at Nostrand Avenue, and lunch at a Brooklyn landmark, Brennan and Carr.

Photo courtesy flickr.com.

Outside and inside, Brennan and Carr looks like an old roadhouse, probably little changed since it opened in 1938. They are renowned for their roast beef sandwiches but I opted for a roast pork sandwich instead, the meat sliced very thin and the whole thing was very tasty. That and a plate of sweet potato fries made for a nice lunch indeed. The staff were very hospitable and helpful to this guy with a cane. I’ll be back.

There’s one more old Dutch farmhouse in Brooklyn to visit: the Wyckoff House in East Flatbush. And I should visit the Flatbush Dutch Reformed Church, built between 1793 and 1798. This walk wasn’t physically taxing and there isn’t much of note in the streetscape, but I walked through a diverse area with a lot of history. I’m glad I did it, on a very pleasant December day.

Helpful sign outside a liquor store on Avenue S.

Holiday display on East 40 Street.

High Kingsbridge and Low Kingsbridge

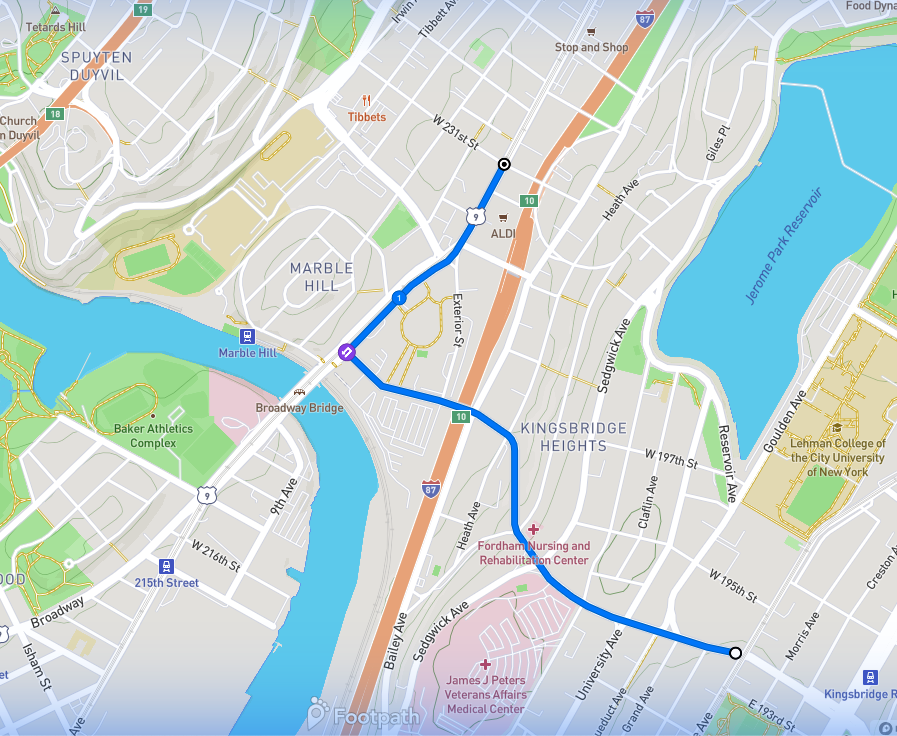

Map of this walk, reading from bottom to top.

WHERE: The Kingsbridge section of the Bronx

START: Kingsbridge Road subway station (4 train)

FINISH: 231 Street subway station (1 train), fully accessible

DISTANCE: 1.28 miles (2.06 kilometers)

Photographic credits as noted. Map courtesy footpathmap.com.

This day’s walk was supposed to have been longer, taking in a lot of pre-World War II architecture on the upper Grand Concourse before ending up in Kingsbridge. My friend Joe was the only person who joined me, so we did a different walk. What this walk lacked in distance was offset by physical challenge. Walking downhill is harder by far than walking down stairs. This walk featured a long, steep downhill on West Kingsbridge Road.

We started at the massive Kingsbridge Armory, possibly the largest armory ever built. It was constructed between 1912 and 1917 and covers all of a 5-acre (2 hectare) site. It was designated a city landmark in 1974. At that time the city's Landmarks Preservation Commission called it "an outstanding example of military architecture." The building fell into disrepair and title to it was transferred to New York City in 1996. Before that time and since, there have been several plans for re-use of the armory, none of which have come to fruition as the City and the community have been unable to develop a common vision for the armory. Meanwhile, it stands mute and unused. Outside the armory along West Kingsbridge Road were people selling all manner of stuff. Laid out on a blanket was an assortment of women’s wigs. I wish I had photographed all this. I might have to go back soon.

Kingsbridge Armory, looking west along West Kingsbridge Road from the elevated subway station. Photograph courtesy curbed.com.

We continued west on a gentle uphill past University Avenue and the Old Croton Aqueduct crossing, before beginning a tough downhill to the Major Deegan Expressway (Interstate 87) starting at Webb Avenue (for which the Webb Institute of Naval Architecture was named) and the Bronx Veterans Affairs Medical Center. This descent was 138 feet (42 meters) in 0.39 mile (0.63 kilometer), or 6.7 percent. Some sense of this can be gained from the following screenshots from Google Earth, proceeding west.

The rest of the walk was unremarkable, going past a large shopping center across from which is a large public housing complex. These were built on the bed of the old Spuyten Duyvil Creek. For more about this area go to my post “Over Hill and Through Riverdale” on the page “The Stair Streets of New York City.”

For me to walk down a steep hill requires care and mindfulness. Looking down the hill from Sedgwick Avenue, I said to Joe, “I’m not liking this hill.” I was concerned by the steepness of the hill and uncertain about the condition of the sidewalk. But I wasn’t going to go back to the Kingsbridge Armory, so we pressed on, carefully and successfully. I felt a lot of satisfaction after this walk.

A Basketball Court and a Ghost Railway

WHERE: New Rochelle and Pelham, New York

START: New Rochelle station (Metro North Railroad, New Haven Line, and Amtrak), fully accessible

FINISH: Pelham station (Metro North Railroad, New Haven Line), accessible at the eastbound (outbound) platform

DISTANCE: 2.0 miles (3.2 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl except as noted. Map courtesy footpathmap.com

Route of this walk, reading from right to left.

I’ve recently met an abstract artist, Scott Albrecht, whose work I like a lot. Scott is also a very kind and intelligent soul. He designed the surface of a basketball court in a city park in New Rochelle, just north of New York City. I was determined to have a look for myself and combined that with a visit to one of the few remaining vestiges of the New York, Westchester and Boston Railway north of the Bronx. The route was fairly hilly, making for a decent workout on a crisp late November day.

The walk started at the New Rochelle station of Metro North and Amtrak. From the station house at the westbound (inbound) platform I walked up the ramp to North Avenue and turned left. There was a fully accessible detour around where North Avenue crosses the New England Thruway (Interstate 95) owing to the rebuilding of the North Avenue crossing. I continued a few blocks up North Avenue, through a tired-looking commercial strip, then crossed and turned left on Lincoln Avenue. A few blocks on, I crossed Malcolm X Way then crossed to the opposite (south) side of Lincoln Avenue and turned right. At this point Lincoln Avenue is on a steep-but-not-too-steep hill, and on the left was my first stop, Lincoln Park.

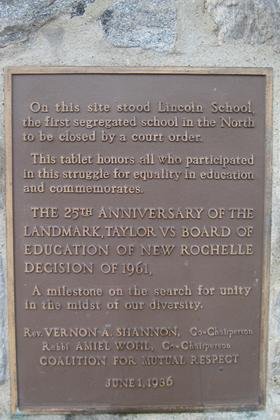

Lincoln Park is on the site of Lincoln School, a segregated public school that was closed by court order in 1961 and subsequently razed. This history is memorialized on a plaque on Lincoln Avenue near the corner of Prince Street.

Just inside the park was the basketball court I was looking for. This was completed in 2018 in partnership with Project Backboard and the National Basketball Players Association. Seeing an aerial view, I had to see it at ground level. I was not disappointed.

Image courtesy Google Earth. Lincoln Avenue is at the bottom.

For all the life and activity there is on a basketball court, it can be a pretty humdrum place, just a rectangle of asphalt. The Lincoln Park court is something special, a gift to a diverse community that might have been overlooked. Perhaps this can be viewed as a mural put not on a wall but on an athletic surface. Scott Albrecht’s horizontal mural fills its space differently than the usual vertical mural would, leading to a different interaction. The patterns on the court could be seen as mimicking how a player maneuvers in a basketball game. It is not representational art. It’s not what’s there; it is what we see. This place allows one to see and imagine many things while shooting hoops or, as I did, just looking on. I’m glad I came here, for it is a special place.

Leaving the park, I continued uphill (west) on Lincoln Avenue through a tidy neighborhood. The sidewalks were in good condition and most of the curb cuts were. At the boundary between the City of New Rochelle and the Village of Pelham (pronounced pell-um) I saw this.

A short distance on I turned left onto Highbrook Avenue, stumbling but not falling as I did so. Suffice it to say that the sidewalks in leafy Pelham could benefit from some attention. Ahead of me was the Highbrook viaduct, built by the New York, Westchester and Boston Railway.

I’ve written about the “Westchester” after several previous walks in the Bronx. This state-of-the-art (for 1912) commuter railroad was a spectacular failure, built by the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad and essentially competing with the New Haven. After service on the “Westchester” ended on the last day of 1937, little effort was spared to eradicate it from the landscape, especially in Westchester County. It seems strange, then, that this substantial structure was left standing. Just west of here was the railroad’s Mount Vernon Junction, from which two tracks went north to White Plains and two went east to New Rochelle (later to Port Chester). The Highbrook viaduct is on what was the Port Chester branch. Part of the right-of-way east and west of the viaduct is now preserved as a park. Just past the viaduct is this historical marker.

Just past this marker I turned onto Harmon Avenue in the direction of the Pelham station. Harmon Avenue has many fine old houses, one of which, number 65, really caught my eye.

Lunch was at a nice neighborhood restaurant across from the Pelham station called The Rail House.

This was a good, enjoyable walk with the benefit of public art along the way. Thanks to Scott Albrecht for creating the work that got me up there. There is so much to see if we just open our eyes and minds.

Back to the George Washington Bridge

WHERE: The north walk on the George Washington Bridge, from New York to New Jersey and back

START/FINISH: 175 Street subway station (A train), fully accessible; also several Bronx bus lines and the M4 bus

DISTANCE: 3.3 miles

Photographs by Michael Cairl except as noted. Map courtesy footpathapp.com.

Map of this route.

In 2021 I posted “The George Washington Bridge” about a walk I took over this bridge, from Manhattan to New Jersey and back. Earlier this year the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey re-opened the footpath on the north side of the bridge after years of improvements, including making it fully accessible. The Port Authority is now rebuilding the footpath on the south side, on which I did the 2021 walk. I took advantage of an unseasonably warm October Saturday to walk the new footpath and, incidentally, mark the 92nd anniversary of the opening of the bridge.

This walk started a few blocks from the bridge, at West 177 Street and Fort Washington Avenue, taking the elevator from the 175 Street subway station. One block north is the George Washington Bridge Bus Station, the terminal for many local New Jersey and New York bus routes and some longer-distance buses. This opened in 1963 and is a rare structure in the United States designed by Pier Luigi Nervi (1891 - 1979), an Italian structural engineer who was noted for the innovative use of reinforced concrete in construction. For more information about this engineering genius go to https://pierluiginervi.org/.

George Washington Bridge bus terminal. Image courtesy nycrc.com.

The entrance to the north footpath is at West 180 Street and Cabrini Boulevard, five short blocks from the subway elevator. Flanking the entrance is some seating to the south, which was most welcome at the end of the walk, and some tables and seats to the north.

Up the ramp and before the bridge is an area with an historical panorama of the bridge. It’s interesting and well done.

Once the south walk of the bridge is reopened, it will be primarily a bicycle path. In the meantime both bicycles and pedestrians share the north walk, which is wide enough to accommodate both groups comfortably. That is a good thing; on this day, while there was a good amount of foot traffic, there were a lot of cyclists. I was once one of them.

At mid-span the state line is clearly marked.

The day offered some spectacular views.

View from the New York side of the bridge, Barely visible in the distance is the new Tappan Zee Bridge, officially the Mario Cuomo Bridge, 17 miles away.

View from the New Jersey side of the bridge.

Just past the New Jersey end of the bridge is a serpentine ramp leading to Hudson Terrace in Fort Lee, and a set of 42 stairs for those wishing a shorter trip. Before the reconstruction of the north walk there was a footbridge over the ramp to the Palisades Interstate Parkway, with stairs on either side (to the bridge and to Hudson Terrace) and a metal channel bolted to the stairs so one could roll a bicycle up and down. The new stairs do not have or need this. There is another set of 10 stairs going up into Palisades Interstate Park. I went up into the park and walked a short distance along the Long Path. I had to walk very carefully to avoid tree roots and stones and the occasional muddy area. But this walk was rewarded by some nice views of the bridge.

Coming back to Manhattan I took advantage of the seating area and chatted with some cyclists who had seen me walking as they rode to New Jersey and back. One of them, Marcos, ended up being the interpreter as they were all Spanish-speaking. I keep running into kind and interesting people on these walks. I am blessed.

Kudos to the Port Authority for doing such a great job rebuilding the north walk! It was a pleasure to walk this. Maybe add some seating in the large open areas they added by the two towers.

And just throwing this in: a picture I took of the George Washington Bridge in 1988, from just south of Fort Tryon Park. Pure luck: right place, right time. 50 mm lens on a Canon AE-1, Kodachrome 64 film.

Eastern Parkway (Brooklyn)

WHERE: Eastern Parkway and a detour into the northern part of Crown Heights, Brooklyn

START: Eastern Parkway - Brooklyn Museum subway station (2, 3 trains), fully accessible

FINISH: Crown Heights - Utica Avenue subway station (3, 4 trains), fully accessible

DISTANCE: 2.54 miles (4.09 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl except as noted. Map courtesy gmap-pedometer.com.

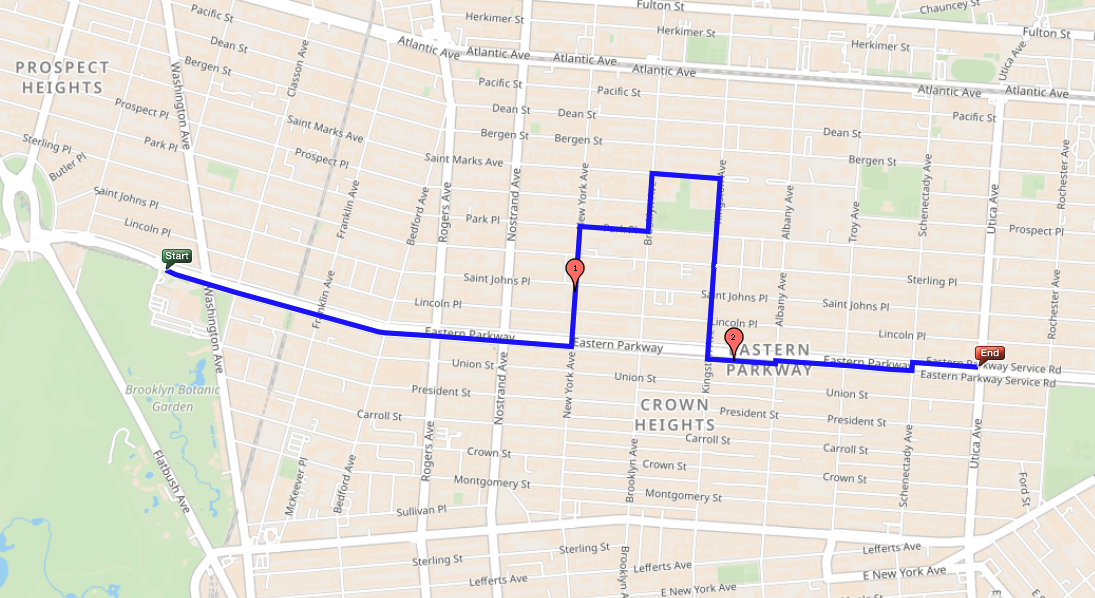

Route of this walk, reading from left to right.

New York City has many streets called “Parkway” but only a few are broad, landscaped avenues, typically with a main road in the middle, landscaped malls on either side, and side roads.

Eastern Parkway, looking east from Rogers Avenue.

In the Bronx, Pelham Parkway, Mosholu Parkway, and Mount Eden Parkway fit this description. In Brooklyn there are Ocean Parkway, going south from Prospect Park, and Eastern Parkway, going east from Grand Army Plaza. These were planned and built in the late 19th century as part of an ambitious plan of civic improvements by the City of Brooklyn. Today’s walk connected two accessible subway stations on Eastern Parkway, starting at the Brooklyn Museum, on a cloudless Sunday.

When the Eastern Parkway - Brooklyn Museum subway station was rehabilitated, architectural artifacts from the Museum’s collection were put in the station mezzanine. It’s a nice collection. Here are two examples:

I’ve often said that if New York didn’t have the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Brooklyn Museum would be the City’s pre-eminent art museum. The present building, while large, is only about one-fourth its originally intended size.

The Brooklyn Museum as conceived in the 1890s. Only the front part and some of the interior were built. Image courtesy archimaps.tumblr.com.

The Brooklyn Museum has long had a renowned collection of ancient Egyptian art. My late father told me how much he enjoyed going to the Brooklyn Museum as a youngster to see its Egyptian collection. It has important holdings in other periods of art. In the mid-2000s the Brooklyn Museum added a modern front entrance. People either love it or hate it. I love it for providing a much better entryway to the museum and for its sitting stairs, oriented not straight ahead to Eastern Parkway but toward Washington Avenue just to the east, and to the rest of Brooklyn. This physical orientation coincides with the Brooklyn Museum doing a better job of embracing Brooklyn’s artists and being more a part of where it is. To me, the YO/OY sculpture out front encapsulates perfectly this sense of place, of the spirit of Brooklyn. It says something different depending on how one sees it.

From the Museum, walk east on Eastern Parkway on the pedestrian (narrower) side of the bike-pedestrian path. Along the pedestrian paths on either side of the main road are plaques honoring local men who died in battle in World War I. Here’s an example near Washington Avenue in honor of Private George A. Greb.

At Bedford Avenue look just to the right at the huge Bedford Union Armory, now called The Major R. Owens Health and Wellness Community Center, named after the late Congressman Major Owens. Opened in 1903, the former Bedford Union Armory served as a dirt-floored training facility and stable for the Army National Guard’s horseback units. After sitting abandoned for decades, redevelopment began in 2015 with the goal of creating valuable community space while preserving as much of the building’s irreplaceable, century-old architecture as possible.

Bedford Union Armory. Image courtesy curbed.com.

Continuing on Eastern Parkway, near the intersection of Nostrand Avenue is the former Loew’s Kameo theater, built in the mid-1920s, now a church. Note the terra cotta ornamentation.

On the opposite side of Eastern Parkway is the former Kings County Savings Bank, now Banco Popular, a sort-of-Art Deco structure from 1930. Quite a grand structure for a neighborhood bank branch, albeit at a major intersection.

At New York Avenue, one block east of Nostrand, the route crosses Eastern Parkway to go north. There are some fine old row houses on New York Avenue.

Many of the avenues intersecting Eastern Parkway are named for cities in New York State: New York, Brooklyn (a separate city until 1898), Kingston, Albany, Troy, Schenectady, Utica, Rochester, and Buffalo. Somehow, Syracuse was overlooked.

At the corner of New York Avenue and Park Place is an imposing structure that, despite its appearance, is not an orphanage. It is the former Brooklyn Methodist Episcopal Home for the Aged and Infirm, built in 1889 as housing for elderly members of Methodist congregations. In 1976 the Methodist Home moved to a new facility in the East New York section of Brooklyn that it still occupies. The old facility lay derelict for decades until it was acquired by the Hebron French-Speaking Seventh Day Adventist School. Much of the complex remains in disrepair, a sad outcome for this gloomy yet stunning place.

Turning right onto Park Place, walk on the side opposite the Methodist Home, as the sidewalk is in better condition. Turn left onto Brooklyn Avenue. On the opposite side is Brower Park, and in the park between Prospect Place and St. Marks Avenue is the Brooklyn Children’s Museum, the oldest children’s museum in the world (1899).

Brooklyn Children’s Museum extension (opened 2006, Rafael Viñoly Architects).

Turn right onto St. Marks Avenue and then right onto Kingston Avenue, continuing the circuit of Brower Park. At the corner of Park Place is the magnificent Historic First Church of God in Christ. The congregation purchased this property in 1939 and transformed it from a bus garage.

Continue to and cross Eastern Parkway, then turn left onto Eastern Parkway. At the southwest corner is 770 Eastern Parkway, the headquarters of the Lubavitcher Chasidic community. Across Kingston Avenue is the Jewish Children’s Museum (opened 2004, architects Gwathmey Siegel) with its outsized dreidel in front.

In front of 770 Eastern Parkway.

Jewish Children’s Museum.

Walk east on Eastern Parkway on the pedestrian (right) side of the pedestrian/bike path; it’s in better condition than the sidewalk. Continue three blocks to Schenectady Avenue, cross and turn right on Eastern Parkway. Finish the walk at the elevator to the subway station at Utica Avenue, across from which is St. Matthew Roman Catholic Church. Two other Catholic parishes, St. Gregory the Great and Our Lady of Charity, worship here.

Eastern Parkway offers a beautiful walk and much to look at along the way. It is an elegant boulevard through an ever more diverse community. The detour north of Eastern Parkway was rewarding for a look at buildings both magnificent and unexpected.

Lower Manhattan Old and New

WHERE: Battery Park, Battery Park City, World Trade Center

START: Bowling Green subway station (4, 5 trains), fully accessible

FINISH: Fulton Transit Center (2, 3, 4, 5, A, C, J trains), fully accessible

DISTANCE: 1.9 miles (3 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl except as noted. Map courtesy gmap-pedometer.com.

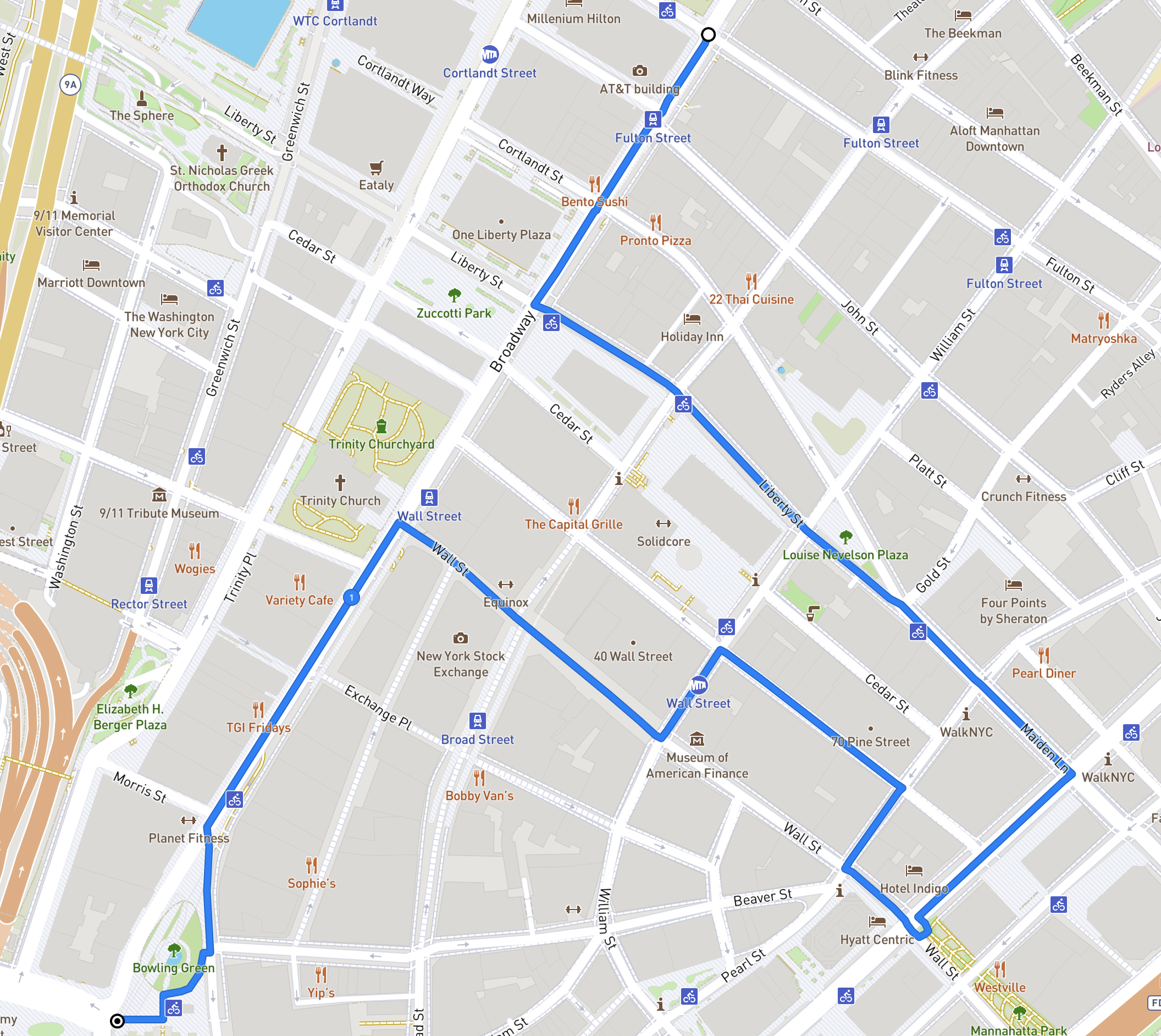

Map of this route.

Much of Lower Manhattan is built on landfill, the shoreline having been extended over the centuries. Water Street was once at the East River shoreline. This walk took in Battery Park, some of which is on fill, and Battery Park City, all of which is, before going past the World Trade Center.

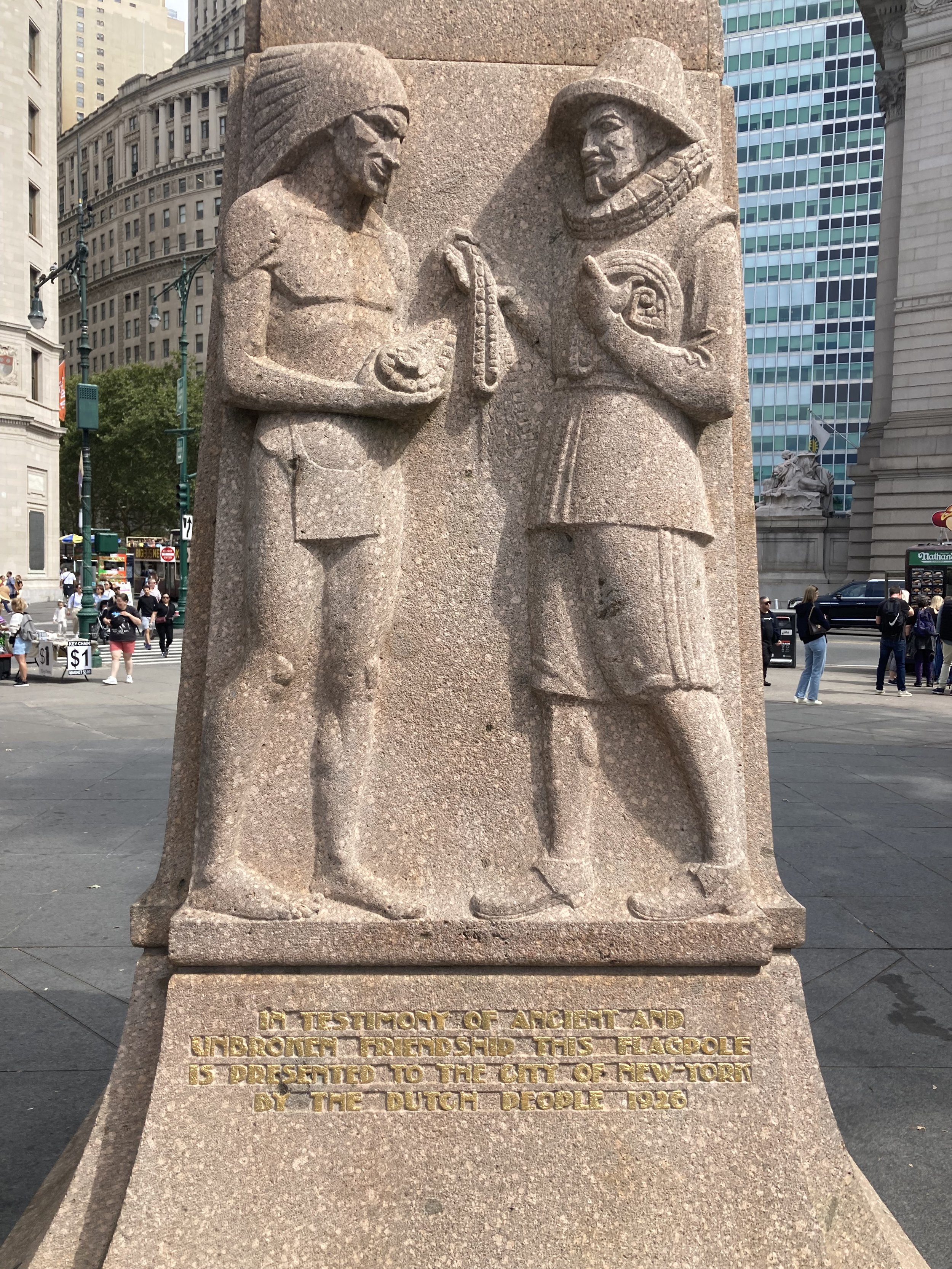

This walk began at the Bowling Green subway station, in front of the old U.S. Customs House that now is home to the Heye Foundation - Museum of the American Indian (a unit of the Smithsonian Institution), and the U.S. Bankruptcy Court. Cross State Street and bear slightly to the left to see the Netherlands Monument, donated by the Netherlands in 1626 on the three-hundredth anniversary of the founding of New Amsterdam.

From the Netherlands Monument walk back toward State Street and turn right. Directly ahead is the original (and still in use) entrance to the Bowling Green subway station, which opened in 1905. This is similar to other street-level control houses built for the first subway.

Continue walking along State Street, alongside Battery Park. At Bridge Street there is a memorial to John Ericsson (1803 - 1889), naval architect, engineer, and builder of the U.S.S. Monitor that fought in the Battle of Hampton Roads in 1862.

John Ericsson holding a model of U.S.S. Monitor.

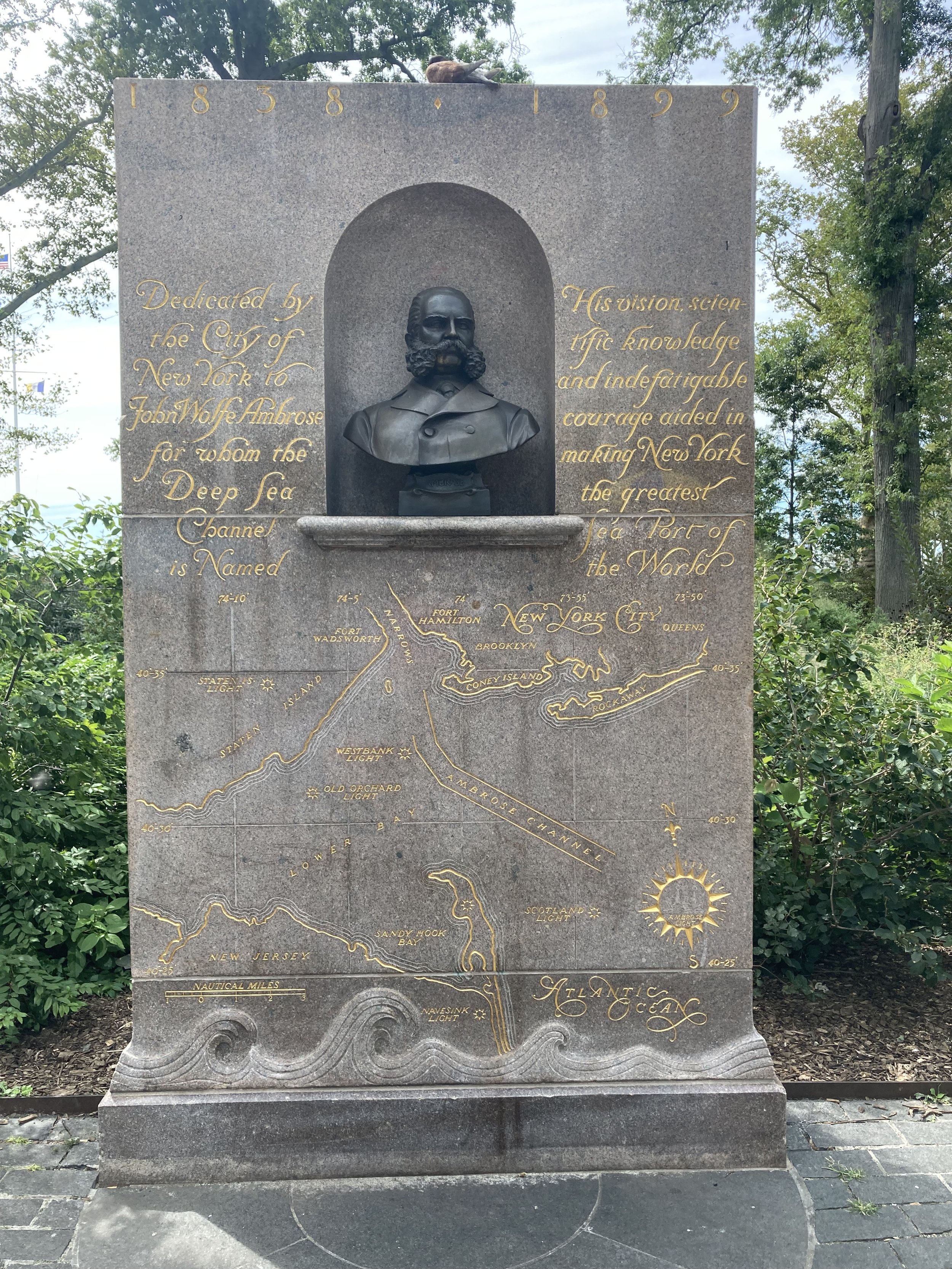

Continue walking. At Pearl Street is a memorial to John Ambrose (1838 - 1899), whose vision and persistence resulted in the deep sea channel to New York Harbor, which improved the visibility of the Port of New York, making New York City the heart of commerce in the United States. This channel is named in his honor, as was the Ambrose lightship off Sandy Hook, at the entrance to the harbor. More about Ambrose can be found at https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=145669.

Just past the Ambrose monument, turn right into the park, passing a playground on the left and a carousel on the right. Passing a restaurant on the left, turn right onto the park path. Ahead is the World War II East Coast Memorial. From the Memorial’s website:

The World War II East Coast Memorial is located in Battery Park, New York City. This memorial commemorates those soldiers, sailors, Marines, coast guardsmen, merchant mariners and airmen who met their deaths in the service of their country in the western waters of the Atlantic Ocean during World War II. Its axis is oriented on the Statue of Liberty. On each side of the axis are four gray granite pylons upon which are inscribed the name, rank, organization, and state of each of the over 4,600 missing in the waters of the Atlantic. For names where an individual’s remains have subsequently been accounted for by the U.S. Department of Defense, a rosette is placed next to the name on the memorial to indicate that the person now rests in a known gravesite.

Photograph courtesy American Battle Monuments Commission

Continuing on past the World War II East Coast Memorial, we come to a monument to Admiral George Dewey, commander of U.S. naval forces that defeated the Spanish at the Battle of Manila Bay in 1898.

Next is the Castle Clinton National Monument. This was built on an artificial island in 1812 as part of a network of defenses of New York Harbor, others being Fort Wadsworth on Staten Island and Fort Lafayette in Brooklyn, the latter having been demolished to make way for the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge. Fort Clinton was was never used for warfare and its cannons never fired a shot. In 1824, the New York City government converted Fort Clinton into a 6,000-seat entertainment venue known as Castle Garden, which operated until 1855. A popular Swedish opera singer of the 1850s, Jenny Lind (“the Swedish Nightingale”), performed here. Castle Garden then served as an immigrant processing depot for 35 years. When the processing facilities were moved to Ellis Island in 1892, Castle Garden was converted into the first home of the New York Aquarium, which opened in 1896 and continued operating until 1941. The Aquarium re-opened in Coney Island, Brooklyn in 1957.

Walk around Castle Clinton on the seaward side, then turn to the left on the path going back toward the water. To the left is New York’s Korean War Memorial.

Take the ramp down toward the promenade. On the left is City Pier A. It was built from 1884 to 1886 as the headquarters of the It was built from 1884 to 1886 as the headquarters of the New York City Board of Dock Commissioners (also known as the Docks Department) and the New York City Police Department's Harbor Department. Pier A, the only remaining masonry pier in New York City, contains a two- and three-story structure with a clock tower facing the Hudson River. The pier is a New York City designated landmark and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Until 1992 it was a fireboat station and was later redeveloped as a restaurant and events venue.

Cross Battery Place and turn left, passing the Museum of Jewish Heritage across the street. Continue to 2 Place and turn left, walking toward the river. Walk up to a 2-piece sculpture of African musical instruments and turn right. At 3 Place, turn left onto the Battery Park Esplanade, staying on it as it turns right to parallel the river.

Battery Park City, where we are now, is built on a large landfill where there used to be piers on an active waterfront. With the rise of containerized shipping after World War II, most of the port’s cargo traffic moved to New Jersey, leaving once-busy piers and adjoining areas derelict. The start of construction of the World Trade Center in the late 1960s provided the impetus to do something with the rotting piers. They were removed and the shoreline was expanded westward. The first apartment buildings arrived in Battery Park City in the late 1970s.

Continue on the promenade to where it turns right at the marina. On your right is the New York City Police Memorial. The names of police officers who died in the line of duty are inscribed on the wall.

Make your way to and into the glass atrium called the Winter Garden. It opened in 1988 as a public space that also hosts concerts and art exhibits. It was heavily damaged in the attack on September 11, 2001 and was rebuilt. The twelve live palm trees are a notable feature of the Winter Garden.

Walk past the grand staircase and exit the building, then proceed to the crossing of West Street to the left and cross here. Once across West Street, cross Fulton Street and turn left. One World Trade Center is on the left. On the right is the North Tower Pool, part of the 9/11 Memorial. This occupies the footprint of the north tower of the World Trade Center that was destroyed in 2001. Names of people who died in the attack are inscribed on the parapet surrounding the pool. Linger around the memorial or continue along Fulton Street past Greenwich Street (restored with the reconstruction of the World Trade Center site) and Church Street. Continuing along Fulton Street, St. Paul’s Chapel (1770) and churchyard are on the left. Cross Broadway and finish the walk at the Fulton Transit Center.

There is so much history on this walk, and outstanding views of the harbor. Most of the walk is off city streets. I did this walk on a very pleasant day. Pick a nice day and do it yourself.

Manhattan Bridge, and then some

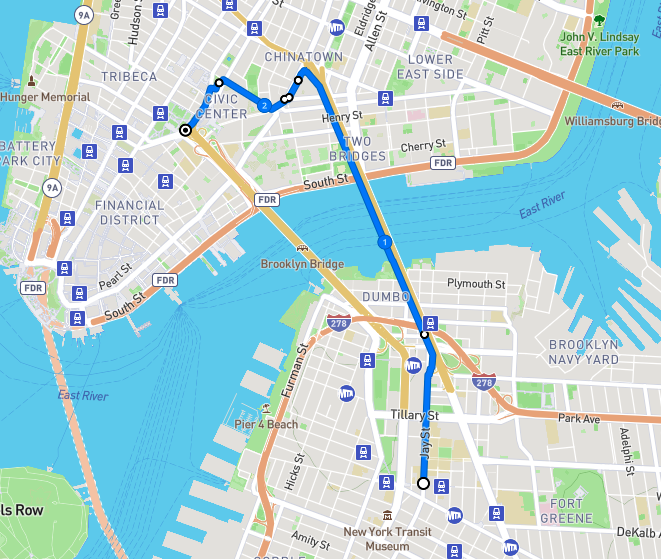

Route of this walk, reading from bottom to top. Map courtesy footpathmap.com.

WHERE: To, across, and from the Manhattan Bridge, going from Brooklyn to Manhattan.

START: Jay Street - Metrotech subway station (A, C, F, R trains), fully accessible

FINISH: Brooklyn Bridge - City Hall subway station (4, 5, 6 trains), fully accessible and connected to the Chambers Street subway station (J train), also fully accessible