This is the Bronx????

WHERE: Pelham Bay Park and City Island, Bronx

START: Pelham Bay Park subway station (6 train), fully accessible

FINISH: City Island Avenue and Fordham Street, then Bx29 bus to Pelham Bay Park subway station

DISTANCE: 3.3 miles (5.3 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl except where noted. Directional map courtesy Apple Maps.

Route of this walk.

This walk was a logical follow-up to a walk I did in this area a year ago; see my post entitled “East Bronx Ramble 2” on this page (East Bronx Ramble 2 — ON FOOT, ON WHEELS). It was my first visit to City Island in over 10 years. In pre-stroke days I biked to City Island a few times. From my home in Brooklyn the round trip was 45 miles (72 kilometers) and made for a nice day trip. City Island is often characterized as looking like a New England fishing village, and it does look like one, more or less.

The starting point for this walk was the last stop on the 6 train, Pelham Bay Park. One enters the park directly across from this station. This area was, until the late 19th century, a collection of private estates and natural wetlands, suggested by this map from 1868:

Image courtesy New-York Historical Society.

From the NYC Parks website:

In 1888, the New York State legislature established this park, the city’s largest, and five others in the borough, creating a Bronx parks system after years of advocacy by the New York Park Association.

For decades the park remained largely unimproved except for upgraded approach roads, provisional bathhouses and extensive camping facilities at Orchard Beach. By 1911, the park had been improved with the addition of athletic fields, play equipment, tennis courts and an 18-hole golf course. During World War I, a massive naval training facility occupied a portion of the park, and in 1922 Isaac Rice Stadium was completed (demolished in 1999). In 1933 the impressive Bronx Victory Memorial was dedicated in tandem with a tree grove commemorating those lost in the war.

In the late 1930s, Parks Commissioner Robert Moses initiated a massive park renovation. A second golf course was added named Split Rock. The most ambitious project was a reinvented Orchard Beach, designed by Gilmore D. Clarke and Aymar Embury, created by dredging sand from the Long Island Sound to connect Hunter Island and Rodman’s Neck. This crescent-shaped “Bronx Riviera” features a massive parking field and two enormous Art Deco-style bathhouses. In 1947, the beach was extended 1.25 miles by filling in shallow areas of LeRoy’s Bay, adding 115 acres of parkland.

More recently, the 375-acre Thomas Pell Wildlife Refuge was created in 1967, and given its sheer size and complexity Pelham Bay Park remains a work in progress, its many amenities and scenic shoreline serving as a local and regional destination.

Compare the map below, dating from 1918, with the 1868 map. By this time the whole area shown was part of New York City and. the newly created Bronx County, not Westchester County. Wetlands and shoreline were being filled in. The New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad’s Harlem River Branch (today part of Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor) and the City Island Bridge (about which more later) had been built.

Image courtesy alamy.com.

The Bronx Victory Memorial was something we saw early on the walk. It commemorates the Bronx residents who died in World War I. Sadly, the plaza in front of it needs some tender loving care,

Not too far along we crossed the Pelham Bay Bridge, which opened in 1908. The sidewalk accommodates pedestrians and cyclists and is too narrow.

In the left background are Amtrak’s Pelham Bay drawbridge and Co-op City.

Just past the bridge we turned right onto City Island Road. This has a bike and pedestrian path on either side of the road. The path and its surrounds make you forget that you’re in New York City.

In the background of the above image, the path ascends one of the very few hills on this route. The other side of that hill is a gentle down slope, past the end of which is the Turtle Cove golf course across the road followed by a traffic circle where one can go to Orchard Beach (no bike/pedestrian path), Rodman’s Neck, or City Island. Rodman’s Neck, a peninsula jutting into Eastchester Bay, hosts the New York Police Department’s pistol range and bomb disposal unit.

Not far from the traffic circle we arrived at the City Island Bridge. The current bridge, with a walkway and bike lane on either side, opened in 2017, replacing a less utilitarian span that opened in 1901 with one sidewalk and no bike lane.

Old City Island Bridge. Photo by Jim Henderson.

Current City Island Bridge, with Rodman’s Neck to the left.

Almost the first thing one notices about City Island is all the boats. Boat docks are appendages of restaurants. A number of yachts that competed for and won the America’s Cup were built at the Minnieford boat yard on City Island.

View from the park near the City Island Bridge. In the distance: 1 - Throgs Neck Bridge. 2 - Bronx-Whitestone Bridge. 3 - One World Trade Center.

Just to the east of City Island, accessible only by ferry, is Hart Island, home of New York City’s potter’s field, with over one million interments.

City Island draws a lot of visitors from the Bronx and beyond to patronize its bars and restaurants. It is a tight-knit, mostly quiet community with a lot of older, small houses on the streets off the “main drag,” City Island Avenue. It doesn’t seem as insular as that other small community on the water in New York City, Broad Channel in Jamaica Bay. Long Island Sound is never far away, and this is the essential character of City Island. I’ve always enjoyed visiting City Island and am glad finally to have returned there. Getting out of my zone is always a good thing, as is doing so on foot.

Lunch was not at one of the numerous seafood restaurants on the island. Too fancy for the occasion. Instead, lunch was at a locals bar and restaurant halfway down City Island Avenue called The Snug. Cold beer and tasty food hit the spot.

Last but not least, I walked over two more of New York City’s walkable bridges today, bringing my total to 43, with 32 to go.

Touchstone (Fort Tilden, Queens)

WHERE: Fort Tilden, on the Rockaway peninsula in Queens

NEAREST TRANSIT: Q35 bus

Battery Harris East and the stairs leading to the viewing platform, Fort Tilden.

Fort Tilden, part of the Gateway National Recreation Area, is located on the Rockaway peninsula between Jacob Riis Park to the east and Breezy Point to the west. From the National Park Service website, it is “a former military site that overlooks the approach to New York Harbor and today includes athletic fields, hiking trails, an arts center, a theater, and an observatory deck on a historic battery offering spectacular views of Jamaica Bay, New York Harbor, and the Manhattan skyline. Dunes, a maritime forest, freshwater ponds, and coastal defense resources including Battery Harris and the Nike Missile Launch Site are also found here.” The New York Times had a fine article about Fort Tilden in 2006 that began thus:

To reach the beach at Fort Tilden, keep the missile silos on your right, the munitions buildings on your left, and head due south of the cannon batteries.

Remember this, because there are no signs to point the way, no scents of sunscreen, lifeguard's whistles nor flying Frisbees; just these military landmarks, the briny breeze and the roar of the surf.

Once over the dunes, it may well be just you and a few stoic surfcasters there with the gulls and terns swooping and flopping on the breeze. The only clue you are still in New York City may be the hazy Manhattan skyline floating 10 miles in the distance.

Most city beaches, Coney Island … for example, have big crowds, murky waters and plenty of Scene. Fort Tilden, a former Army base along the ocean on the Rockaway peninsula, which dangles into the Atlantic Ocean off Queens, is the opposite. It has wide-open and pristine sands, a fresh sea and a rugged beachscape of barnacled bulkheads and sea-softened pilings jutting up out of the sand.

The full article, which is well worth reading, is at https://www.nytimes.com/2006/07/21/arts/to-the-battlements-and-take-sunscreen-the-joys-of-fort-tilden.html?unlocked_article_code=1.Qk8.32XF.AOhnelx0xD_s&smid=url-share. At different times Fort Tilden had huge guns pointed toward the sea; later, Nike missile batteries. The guns and missiles are long gone but many structures remain, among them two huge concrete bunkers that housed 16-inch guns (the same as armed World War II battleships and some earlier ones). These are Battery Harris West and this walk’s destination, Battery Harris East.

For me, Fort Tilden is a special place. Before my stroke, I biked out to Fort Tilden often, to ride around and laze on the beach. The ride out there took about an hour, more in a stiff headwind. Very occasionally I would walk up to the top of Battery Harris East. By the summer of 2020, I hadn’t been there since before the stroke. One day, I had the urge to go out there and see if I could manage the steps up to the observation platform atop Battery Harris East. I walked about a mile (1.5 kilometers) from the bus stop to the base of the steps, had a look, and decided, “I can do this.” Up I went, 69 steps to a sandy and not easy path to the platform, another 4 steps up. Riding the bus back to Brooklyn, I thought to myself, “Next up: the 215 Street stairs in Manhattan.” And so it happened. After that climb, a friend mentioned the Joker Stairs in the Bronx, and off I went. That 2020 trip to Fort Tilden gave rise to every walk on my “Stair Streets” page, and a good many others.

For this walk I wanted to repeat that 2020 stair climb, and I did. The risers are a bit high but the stairs are in good shape. That sandy path between the top of the stairs and the observation platform must still be walked with care. It was a warm day but there was a steady, cooling breeze off the ocean. I truly felt revived and hated to leave. It was important for me to do this, to stay centered, to keep pushing myself and have fun doing so.

ONWARD!

Route of this walk.

The Marine Parkway - Gil Hodges Memorial Bridge from the observation platform.

The Atlantic Ocean from the observation platform.

Yours Truly, with the Manhattan skyline in the background..

Jamaica, Queens

Map courtesy Apple Maps.

HOW TO GET THERE: The Long Island Rail Road; the E, F, and J subway lines; many bus routes; the JFK AirTrain.

I wasn’t going to post about a short walk that I did on the spur of the moment, that didn’t seem very interesting at first. After some reflection I realized there was more of Jamaica about which to write than what I saw on the walk.

Jamaica has been a commercial and transportation center in Queens for over 200 years. The first segment of the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) opened from Brooklyn to Jamaica, a distance of 9 miles (14.5 kilometers), in 1834. It roughly paralleled the Jamaica Turnpike, now Jamaica Avenue, that connected with the road to Fulton Ferry in Brooklyn. Through the 19th century the LIRR expanded west of Jamaica and east on Long Island. Jamaica Station, a trainspotter’s paradise, is the busy hub of the LIRR (the busiest commuter railroad in the United States), a station for the E and J subway lines, a stop or terminal for many local bus lines, and an end point for the JFK AirTrain.

Several courthouses and federal, state, and city government offices are in Jamaica. My former co-worker Elaine, who grew up in College Point, Queens, talked about what a treat it was to take the bus to the big department stores in Jamaica, especially the flagship store of Gertz. Macy’s and Montgomery Ward also had branches there. A daily newspaper, the Long Island Press, was printed in Jamaica for over 150 years. But since the 1960s the big stores and the Long Island Press have gone. The Gertz building has undergone transformations and Rufus King Park is an oasis, but Jamaica Avenue and Sutphin Boulevard look tired.

The JFK AirTrain opened in 2003 and abetted the notion of Jamaica becoming an “edge city” tied to JFK Airport. Since then there has been a lot of new development, mostly near Jamaica Station. The photos below show the evolution of Jamaica Station: on the left, the station building (1913), housing LIRR offices; on the right, the station and new high-rise development.

Anyone who has looked out the window of an LIRR train east of Jamaica Station will have noticed that Jamaica has a definite “this side of the tracks, that side of the tracks” aspect. South of the LIRR Main Line, Jamaica is much less built up than north of the tracks, with the notable exception of the York College campus of the City University of New York. There seems to be ample space and opportunity here for new development, in particular housing that is truly affordable. Jamaica has some of the best public transportation in New York City. This kind of development would also be a shot in the arm for business in Jamaica. This need not be incompatible with the notion of an “edge city” because JFK is a jobs generator and Jamaica is a potential beneficiary thanks to its proximity to JFK. In short, Jamaica has too much going for it to become a missed opportunity.

At Jamaica Avenue and 153 Street is the former home of the First Reformed Church of Jamaica, now the Jamaica Center for Arts and Learning (JCAL).

From the website of the American Guild of Organists:

The First Reformed Dutch Church of Jamaica was established in 1702 for Dutch merchants who settled near Jamaica. An octagonal-shaped building with a steeply-pitched roof topped by a cupola and weathervane was erected in 1716. Church history places the original building at about Jamaica Avenue and 162nd Street.

In 1833, the congregation relocated to Jamaica Avenue and 153rd Street where the second church was built. The Georgian-style building included a tower that was topped by a cupola and weathervane. This church building burned In 1857.

The third church [JCAL] was built from 1858-59 on the same site. Designed and constructed by master carpenter Sidney J. Young (a member of the congregation), with the assistance of master mason Anders Peterson, the building with its asymmetrical towers, round-arched openings, and corbel tables shows a sophisticated use of brickwork and reflects the growing popularity and influence of the architectural style known as "Rundbogenstil." Young visited other local churches for inspiration, possibly including the Church of the Pilgrims and South Congregational in Brooklyn. His creation was regarded as one of the finest Early Romanesque Revival churches in New York. A plaque at its entrance notes that it was ''dedicated to the worship of the triune God October 6th 1859.'' This building served the church for more than a century, but by the 1960s downtown Jamaica began a long period of decline. This building was designated in 1966 by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, and in 1980 was listed in the National Register of Historic Places. The old church fell into disrepair was ultimately condemned as part of an urban renewal project. The congregation moved out in the mid-1980s and, after a few years in a temporary base, the settled into its present home at 159-29 90th Avenue.

Jamaica and its surrounds were settled by Dutch farmers and merchants from the late 1600s. My sixth great-grandfather (if he was generation 1, I’m generation 9), Theodorus Polhemus, was born in Jamaica in June 1717. His great-grandfather, Johannes Polhemus, was the founding pastor of three Dutch Reformed congregations in Brooklyn that survive to this day. Theodorus almost certainly went to the First Reformed Church of Jamaica as a youth. He later settled in Rockland County, New York, and died there on 26 November 1789.

Immediately west of JCAL is the Queens County Family Court. The façade on Jamaica Avenue has panels with quotations from the late U.S. Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall (1908 - 1993). This is the first one I saw and boy, did it hit home. It reads, “History teaches that grave threats to liberty often come in times of urgency when constitutional rights seem too extravagant to endure.”

It is fitting that these inscriptions are across the street from the Rufus King Mansion Museum. I arrived during normal opening hours but for some reason the museum was closed.

Rufus King (1755 - 1827) was a signer of the Constitution, a U.S. Senator from New York, and a prominent early abolitionist. The museum was his home.

Reprise: Back to the Henry Hudson Bridge

WHERE: The Inwood neighborhood of Manhattan and the Spuyten Duyvil and Kingsbridge neighborhoods of the Bronx

START: Broadway and Dyckman Street, Manhattan (Dyckman Street subway station, A train)

FINISH: West 238 Street and Broadway, the Bronx (238 Street subway station, 1 train)

DISTANCE: 3.1 miles (5 kilometers)

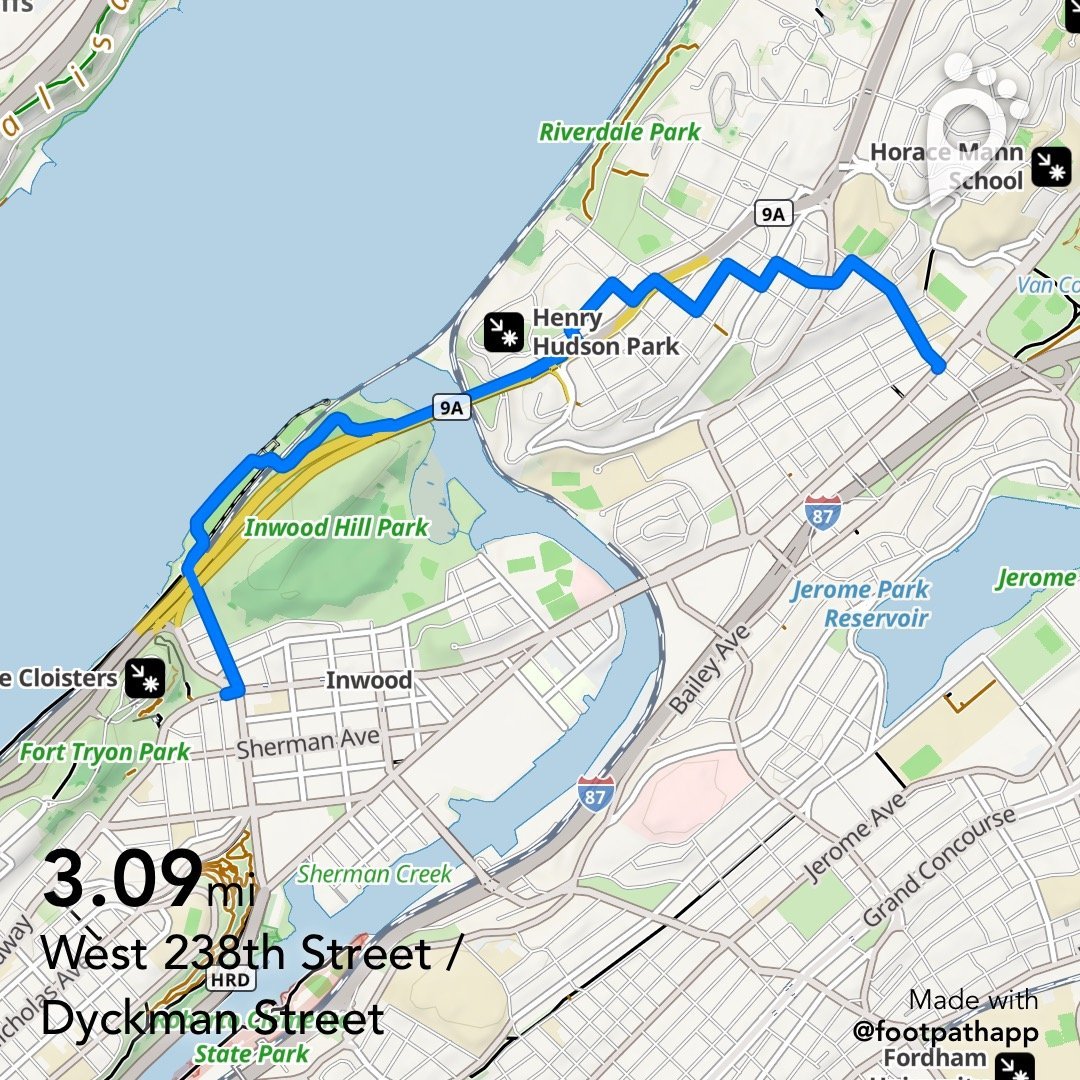

Route of this walk, reading from left to right, courtesy footpathmap.com.

This walk began at a grander than usual subway entrance.

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) recently completed reconstruction of the bike and pedestrian path on the Henry Hudson Bridge. This was the impetus for this walk, mostly a reprise of a walk I led a couple of years ago. See my earlier post “To the Henry Hudson Bridge and Beyond” on the “Stair Streets” page.

The approaches to the bridge path were made accessible and the path on the bridge was more than doubled in width. Approaching the bridge from Inwood Hill Park is still very hilly and a good workout. Below is a below-and-after (July 2022 and May 2025) of the reconstructed Manhattan approach.

From the MTA website:

Named in honor of Henry Hudson, the explorer whose ship, the Half Moon, anchored near this site in 1609, this bridge opened in 1936. It connects northern Manhattan to the Bronx and was built as part of the Henry Hudson Parkway by the Henry Hudson Parkway Authority. When it opened, it was the longest plate girder arch and fixed arch bridge in the world. Originally built with only one level, the bridge's design allowed for the construction of a second level if traffic demands increased. Within a year and a half the upper level was opened. The upper level carries northbound traffic; the lower one is for southbound traffic.

The Bronx approach to the walkway is also accessible, with a new crosswalk to a sidewalk that, while it is uneven, is nicely routed around a magnificent tree.

The rest of the walk repeated the earlier walk except for the 232 Street stairs, and on this walk lunch was at a great old-school Jewish deli on West 235 Street, Liebman’s.

The handrails on the Manhattan College Steps are still too low, and in places are loose, as shown in the images below (thanks, Lewis). The complete set of handrails here should be either raised and properly secured, or replaced. They are unsafe in their current condition. To the city’s Department of Transportation and Bronx Community Board 8: fix this, please.

Marching through Astoria, again, or Piano Piano

WHERE: The Astoria section of Queens

START/FINISH: Ditmars Boulevard subway station (N train)

DISTANCE: 3.4 miles (5.5 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl except as noted. Map courtesy Apple Maps.

“Astoria” covers a number of neighborhoods. This walk started and finished in Astoria proper, long home to people of Italian and Greek background, now home to a lot of young professionals. The walk also traversed the Steinway neighborhood, where a lot of people from Egypt and other countries have settled. But the theme, such as it was, of this walk was pianos.

We started out near the end of the N subway line, at 31 Street and Ditmars Boulevard, a busy commercial area, and walked toward our first stop, the Steinway and Sons piano factory. Steinway grand pianos are found all over the world in concert halls and other music venues, and they have been built right here in Queens for 150 years. From the Steinway website:

This area of New York was once known as “Steinway Village,” a community formed at the end of the 19th century, when Steinway moved its small Manhattan factory to Astoria and began to drive surrounding economic development.

At the northern end of this village is the historic Steinway factory. Each piano built here has been carefully crafted for at least 9 months, and eighty percent of the production process is completed by hand by meticulously trained Steinway craftsmen. A tour of the factory reveals the time-honored processes that have made the name of Steinway an iconic part of American musical history since 1853.

Just west of the Steinway factory is a hulking gray cube called Wildflower Studios. From its website:

Wildflower Studios is New York’s only high-performance TV and film production facility, purpose-built for the unique needs of 21st-century storytelling.

Wildflower Studios is developed by lifelong New Yorker and film industry veteran Robert De Niro and real-estate visionary Adam I Gordon, Raphael De Niro, and designed by the groundbreaking architectural firm Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG).

Our vision is a comprehensive 21st-century tool for storytellers—a village of collaboration, creativity, efficiency, and innovation—finally in New York City.

Wildflower Studios.

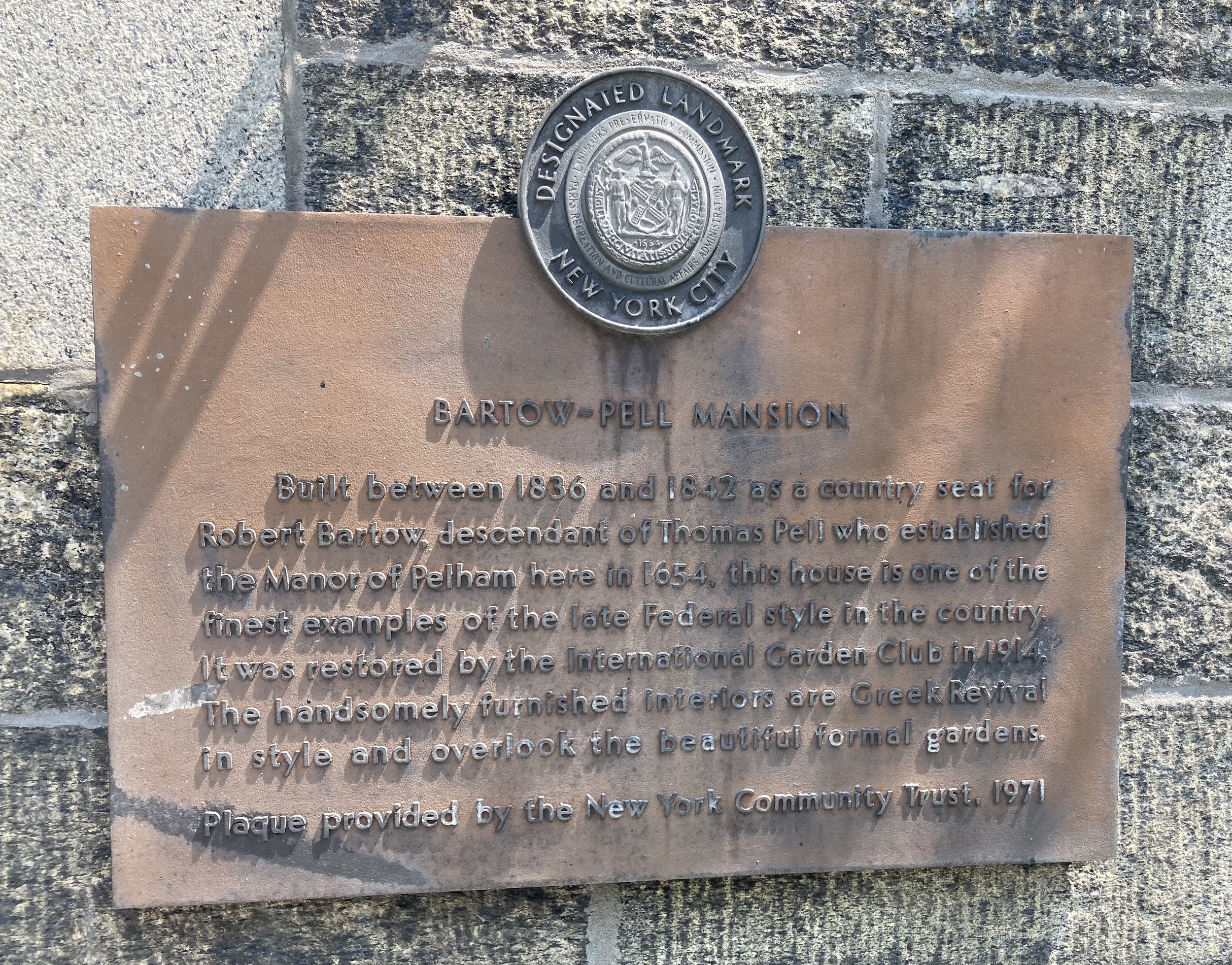

From there we walked a few short blocks to the Steinway Mansion. Built in 1857 - 1858 by Benjamin Pike, Jr., William Steinway purchased the house in 1870. It was designated a New York City Landmark in 1967 and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1983. From Wikipedia:

The Steinway Mansion is a grand Italianate and Renaissance Revival villa-style dwelling, although its architect remains unknown. It is constructed of granite and bluestone with cast-iron ornamentation and has a two-story, T-shaped central section gable roof. Another prominent feature is the four-story tower crowned with an octagonal cupola that was previously surrounded by balustrades.

The mansion was put up for sale … in 2010, but the high price, protected status, and poor condition deterred potential buyers from buying the property. A diverse group of Astoria historians, elected officials, and business leaders formed The Friends of Steinway Mansion in an effort to purchase the mansion out of fears of future mishandling. They were then joined by The Artisans Guild of America, Steinway & Sons, and State Assemblywomen Marge Markey and Aravella Simotas. They were unsuccessful in their attempt to raise $5 million and acquire the house.

After years on the market, as well as numerous price reductions, Sal Lucchese and Philip Loria paid $2.65 million for the property in 2014. Parts of the surrounding land were then developed into commercial warehouses, leaving the mansion on just more than a quarter acre of property. By this time, the nearly 150-year-old mansion was in a state of significant deterioration, and hence, the new owners undertook an ambitious restoration project, which included reconstructing the grand balcony.

In 2022, the Steinway Mansion hosted the annual gala of the Variety Boys and Girls Club of Queens, a fundraising event attended by local public officials and community leaders.

The Steinway Mansion.

In 2006, a documentary titled The Steinway Mansion was produced, featuring extensive interviews with Michael Halberian and Henry Z. Steinway, as well as rare archival photographs. A link to the documentary follows.

From there we walked a few more blocks to the Paul Raimonda Playground, named for an outspoken community leader in Long Island City, Queens. Raimonda attended P.S. 126 and Bryant High School, and served for four years in the Army Air Corps during World War II. Both during his youth, when he was an active member in the Long Island Seneca Club, and in his later years, Raimonda was committed to his community. The Steinway piano is the inspiration for the centerpiece of this reconstruction: a spray shower in the shape of a baby grand piano with four octaves of keys and a replica of the signature Steinway iron plate inside the piano.

The fountain in Paul Raimonda Playground. Photograph by Lewis.

By the piano fountain: Lewis, Yours Truly, Michael, Jennifer, Tessie. Photograph by PJ.

On the way to the playground we passed by some intriguing street art.

Photographs by Lewis.

We continued to lunch at Jackson Hole, formerly (and still signed as) the Air Line Diner. It appears to have been built around 1940, and the old sign includes an image of a trans-Atlantic passenger seaplane for which La Guardia Airport’s spectacular Marine Air Terminal was built nearby.

This was a fine walk on a beautiful day with good company, once again exploring interesting places in out-of-the-way parts of the city.

Crossing Coney Island Creek

WHERE: The Stillwell Avenue Bridge and Cropsey Avenue Bridge over Coney Island Creek, Brooklyn

START/FINISH: Stillwell Avenue - Coney Island subway station (D, F, N, Q trains), fully accessible

DISTANCE: 2.3 miles (3.7 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl except as noted. Map courtesy Apple Maps.

Ah, Coney Island. The beach. Hot dogs. The Cyclone and the Wonder Wheel. The Mermaid Parade. Where for 150 years New Yorkers have gone to frolic by the seaside. Behind all this is a forlorn waterway called Coney Island Creek. A fine closeup of the creek was done by Matt at Two Feet Outdoors in this video.

This walk revived my occasional forays onto the walkable bridges of New York City, and a not-long-for-this-world footbridge over the Shore Parkway.

Setting out from the huge Coney Island subway terminal, my friend Matt (not the kayaker, a different Matt) and I walked north on Stillwell Avenue to the Stillwell Avenue Bridge.

It isn’t much of a bridge, and the view of Coney Island Creek is marred by chain link fencing.

From there we ducked underneath the Shore Parkway and paralleled it for a distance. At this point the parkway is on a. viaduct that crosses over the Coney Island subway yard and past the Coney Island Maintenance Shop, the largest rapid transit maintenance shop in the world. Every part of a. subway car can be overhauled here. From there we walked to the footbridge over the parkway at 27 Avenue. In recent years the New York State Department of Transportation has been replacing the overgrade bridges along the parkway between the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge and JFK Airport to increase vertical clearances, presumably to allow trucks at a future date. The 27 Avenue footbridge is the only survivor of four of the same design. They were gorgeous. Kevin Walsh has a fine piece about these at https://forgotten-ny.com/2023/04/belt-parkway-bridges/.

The 27 Avenue footbridge. Image courtesy historicbridges.org.

The footbridge will be replaced with one that is accessible and has a higher clearance over the parkway. Crossing the old footbridge, which dates from around 1940, was not easy but was worth doing. The construction sign at the end of the footbridge advises that:

Inspired in its historic design, the steel arch bridge will consist of a new roadway, suspenders, stringers and floor beams. ADA ramps, pedestrian railings, historic light poles and a new drainage system will be installed.

We shall see.

At the end of the footbridge is Calvert Vaux Park. A lot of motorists and cyclists speed past and never stop and look. The park borders Gravesend Bay, where British soldiers landed in August 1776 to fight George Washington’s forces in the Battle of Brooklyn. Froom the NYC Parks website:

What was here before?

The Coney Island Creek that runs through the park was once home to small ports and shipyards, and in the early 20th Century was reputedly a rumrunners’ haven. Today the hulls of nearly two dozen shipwrecks can occasionally be seen in the creek at low tide, including a half-submerged yellow submarine built by shipyard worker Jerry Bianco, Quester I, which capsized upon launch in 1970.

How did this site become a park?

The land for this park was obtained through three land acquisitions. In 1933, the Dreier-Offerman Home for unwed mothers and children closed and donated its property to NYC Parks. In appreciation, Parks originally named it Dreier-Offerman Park. In 1962, NYC Parks simultaneously acquired two additional parcels: a small strip of land and a 72-acre tract consisting of property and landfill debris excavated during the construction of the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge. This last acquisition, financed by a 1960 New York State bond act, provided the bulk of the park’s property. In 1998, NYC Parks renamed this open space in honor of distinguished designer Calvert Vaux.

In 2000, NYC Parks rebuilt the playground and added a new public restroom, open lawns, a children’s play area, basketball courts, and a children’s spray shower.

In 2007, Calvert Vaux Park was selected for restoration as part of the City’s PlaNYC initiative, in which eight parks citywide were transformed into attractive regional destinations. The master plan proposal included kayak launches, a central lawn, nature trails, an amphitheater, a playground, a recreation center, and a pavilion. One of the park’s central attractions is the Verrazano Sports Complex, a competitive soccer and baseball center.

Who is this park named for?

The park is named after Calvert Vaux (1824-1895), the noted Victorian-era architect and pioneering landscape architect who co-designed Central and Prospect Parks.

Vaux was born in England and moved to America to study with leading architect in the nation, Andrew Jackson Downing (1815-1852). He designed private homes, apartment complexes, public housing, and many public institutions, as among these the American Museum of Natural History and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the Gothic and Victorian style. His partnership with Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903) generated designs for Central Park, Prospect Park, Morningside Park, and Fort Greene Park. Vaux drowned under mysterious circumstances, and his body was found in nearby Gravesend Bay.

Looking inside Calvert Vaux Park.

From there we made our way to the Cropsey Avenue Bridge, a bascule drawbridge built in 1931 and recently rebuilt.

Machine Age handrail on the Cropsey Avenue Bridge.

Looking east along Coney Island Creek from the Cropsey Avenue Bridge.

From there we walked back to the subway and the end of the walk. This was a fine day for a walk that was easy except for the footbridge, and gave us a slow-speed look at Coney Island Creek and the neglected part of Coney Island.

Another Bit of Old Dutch Brooklyn

WHERE: The Flatbush, Midwood, and Sheepshead Bay neighborhoods of Brooklyn

START: Kings Highway subway station (B and Q trains), fully accessible

FINISH: Flatbush Avenue - Brooklyn College subway station (2 and 5 trains), fully accessible

DISTANCE: 2.3 miles (3.7 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl except as noted. Map courtesy Apple Maps.

This walk, undertaken on an unseasonably warm March day, was a follow-on to the walk I described in the post on this page entitled “A Bit of Old Dutch Brooklyn.” My objective was to see two Colonial-era farmhouses on an easy walk. Both are private property and neither one was open to the public.

I started out at the Kings Highway station on the Brighton line (B and Q trains), then walked east on Kings Highway. The predecessors of today’s Brighton line enabled the transformation of this area in the years following World War I, from semi-rural to urban. The first few blocks of Kings Highway east of the subway are a bustling commercial area, with signs in English and Russian. A lot of people were out and about, everywhere I went. The thrifty shopper could do a lot worse than shop here for everything from fruits and vegetables to household items.

My first stop was the Wyckoff-Bennet Homestead. It was owned by a succession of families before being sold in 2021 by the heirs to the Mont estate. According to New York Historical (the erstwhile New-York Historical Society), “[o]riginally the house faced south, but around 1898 it was turned to face west to avoid having newly-opened East 22nd Street run through its kitchen wing. The slender porch columns supporting the sloping eaves were added then.'‘

A plaque outside the house reads:

This Dutch-American farmhouse is a quiet reminder that the Battle of Brooklyn, one of the biggest conflicts of the Revolutionary War, took place when Kings County was still mostly farm country. The county boasted fewer than 4,000 inhabitants, one third of whom were slaves working on land owned by families descended from 17th-century Dutch immigrants. Hendrick Wyckoff built the house in 1766. The site he chose lay along Kings Highway, then the county's main east-west artery. After the British invasion in 1776, Hessian soldiers were quartered here. Several of them left their mark by etching their names and rank on window panes among them Toepfer Captain Regt. De Ditrurth and "M. Bach Lieutenant V. Hessen Hanau Artillerie's". When the Battle of Brooklyn began on August 27, 1776, these men may well have taken part in the attack that drove American defenders from the Battle Pass, in what is now Prospect Park, and nearly destroyed the army under command of George Washington.

Wyckoff-Bennet Homestead, 1882, Image courtesy New York Historical by way of urbanarchive.org.

Sadly, the house appears to be in disrepair. I fear for its future, notwithstanding that it is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Wyckoff-Bennet Homestead, 2025.

The Wyckoff-Bennet Homestead is where Kings Highway becomes much wider, with a through roadway and side roads. The apartment buildings on this stretch of Kings Highway give it a bit of the appearance of the Grand Concourse in the Bronx.

When crossing Kings Highway, do so only on a complete traffic signal interval; do not attempt to cross once the signal has already turned green.

I continued northeast on Kings Highway, past Bedford Avenue, past Nostrand Avenue, to Fraser Square. It’s actually a roundabout, but never mind. It’s just one more example of Brooklyn’s sometimes confusing street naming. When I would bike home from the Rockaways, my usual route took me past Fraser Square on Avenue M.

According to the NYC Parks website:

Fraser Square, once a barren traffic circle populated by weeds, is now a lush garden oasis and an urban retreat. Designed by Parks Landscape Architect Wim DeRonde with community input, the park features space for repose and small gatherings, as well as pathways leading to a circular plaza. Stop by and take in the wide variety of perennials, shrubs, and trees. … This oval oasis honors the memory of patrolman John Justin Fraser (1897-1934), whose life was cut short by a tragic act of violence.

From Fraser Square I walked north on East 34 Street. This is a residential street of pre-World War II houses, mostly detached. People were taking advantage of the mild weather and the Jewish Sabbath to sit on their porches or chat with the neighbors. Just north of Avenue J was the second farmhouse on my itinerary, the Joost van Nuyse House. From urbanarchive.org:

[Also k]nown as the Stoothoff-Duryea House, it may have been built by Joost Van Nuyse as early as the mid-18th century. Van Nuyse died in January 1792, and likely passed his property on to his son Jacobus, who died on Christmas of 1792 after falling into his well. The following year, the farm and house passed to the family [of] Wilhelmus Stoothoff (and was, in 1796, listed in "middling condition" at a value of $350). Until the 1920s, the house was located on Flatbush Avenue at Avenue J and East 35th Street.

Joost van Nuyse House, 1931. Image courtesy New York Public Library by way of urbanarchive.org.

Joost van Nuyse House, 2025.

From the Joost van Nuyse House I continued north on Flatbush Avenue to the subway station at “the Junction,” as the busy intersection of Flatbush and Nostrand Avenues and its surrounds is known.

This was an easy walk in a part of Brooklyn without hills. Crosswalks and sidewalks aren’t always even so walk mindfully. The walk encompassed plenty of history hiding in plain sight, and a dynamic streetscape in gloriously Never-Cool Brooklyn.

Another Stop on the Trail of Religious Liberty

WHERE: The Gravesend neighborhood of Brooklyn.

Photographs by Michael Cairl.

Map of Gravesend, courtesy Open Street Maps.

What is now New York City became home to two women for whom the Puritans of the Massachusetts Bay Colony had no use. Leading bands of religious dissenters was bad enough, but having them led by women must have been more than the Puritans could stand. These women were Anne Hutchinson (1591 - 1643), who fled to what is now the Bronx, and Deborah Moody (1586 - 1659), who founded the community of Gravesend in the part of New Netherland now known as Brooklyn. I’ve wanted to walk around Gravesend for some time, and a typically excellent and fun video by Tom Delgado (featured at the end of this post) was all I needed to get going. So I picked a cold February day to go there.

From the website of New York Historical (also known as the New-York Historical Society):

Deborah Dunch was born in London, England in 1586. She was the daughter of Walter Dunch, the auditor of the Royal Mint, and his wife, Deborah. Her ancestors were loyal supporters of the British monarchy and the Church of England. She married Sir Henry Moody in 1606, becoming Lady Deborah Moody.

After the death of her husband in 1629, Deborah became an Anabaptist. The Anabaptists were a Protestant sect of Christianity who believed that baptism should not occur until a person was old enough to consent. In England, where the Church of England was headed by the king, Anabaptists were considered a danger to the stability of the nation. Women in particular were vilified for following this religion. When word of her new beliefs got out, Deborah was summoned to appear in court. Rather than face whatever punishment the government had in mind, Deborah gathered her wealth and set sail for the English colonies in North America. She was fifty-four when she arrived in Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1639. The colony was run by Puritans, another Protestant sect that had been forced to flee England. Deborah probably chose it thinking it would be a place where she could practice her beliefs in peace.

The Massachusetts Bay Colony was not the haven of tolerance that Deborah hoped for. Deborah originally settled in the town of Saugus, Massachusetts, before moving to a large farm in Swampscott, just outside of Salem. She conducted a lively correspondence with other people in the area who were not Puritans. This drew the attention of her closest neighbor, Reverend Hugh Peter. Hugh believed that the Massachusetts colony should have religious unity. He had already expelled another Anabaptist woman, Anne Hutchinson, two years prior to Deborah’s arrival. In 1643 Deborah was brought before the court for spreading religious dissent. During her trial, Puritan leader John Endecott described her as a “dangerous woman.” She was given the choice to change her beliefs or be excommunicated from the colony. Deborah chose excommunication, gathered her fellow Anabaptists, and set out once again to find a place where they could practice their religion in peace.

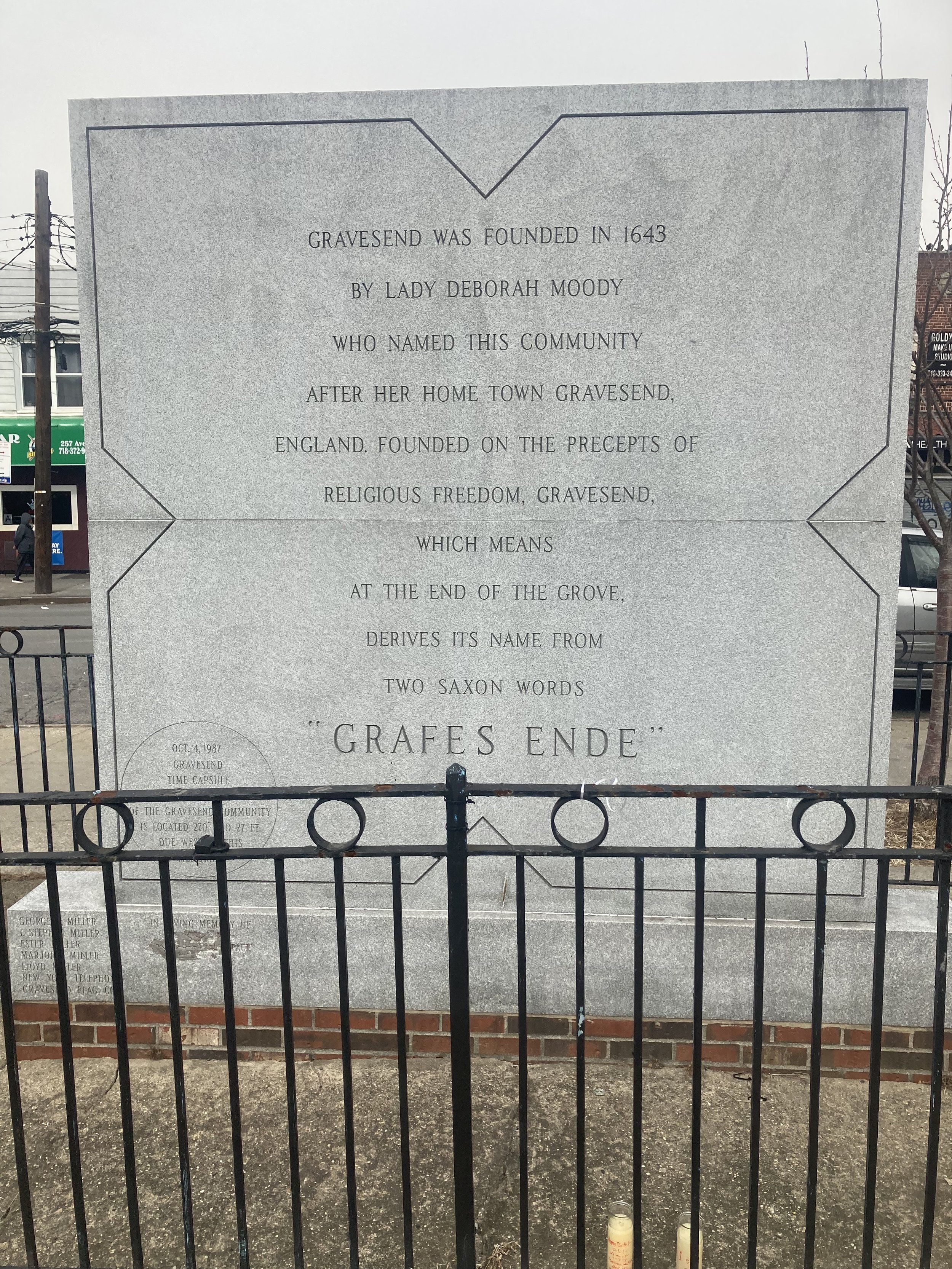

Deborah drew up the plans for her new community and named it Gravesend. It was the first New World settlement founded by a woman.

At the same time that Deborah was standing trial in Massachusetts, Director Willem Kieft of the Dutch West India Company was looking to recruit new settlers to the New Netherland colony. Willem had recently started a war with local Mohawk communities and wanted to increase the colony’s population to make it harder for the Mohawk to take back their land. Deborah was a woman with money who already had followers willing to help settle a new community. The Netherlands and its colonies practiced a greater degree of religious tolerance than England and Massachusetts, so Anabaptist beliefs were less worrisome there. Willem granted Deborah the southwestern tip of Long Island, territory that now encompasses parts of Bensonhurst, Coney Island, Brighton Beach, and Sheepshead Bay in Brooklyn.

Deborah drew up the plans for her new community and named it Gravesend. It was one of the first settlements in the American colonies founded by a woman. She allowed the inhabitants of Gravesend to follow whatever religious practices they chose, so long as they abided by the laws of the colony. Gravesend was targeted by local Native American communities who were angry with the Dutch colonists settling their land. This was no minor threat—in 1643 another outlying settlement in New Netherland was destroyed because of the ongoing conflict. In spite of these very real dangers, Deborah and her followers chose to stay.

As Deborah’s community grew, so did her influence in the government of New Netherland. In 1647 she was among the colony’s elite who greeted the new Director-General Peter Stuyvesant. In 1654 Peter called on her to mediate a tax dispute, and in 1655 she was called upon to nominate magistrates for Gravesend. Deborah lived in Gravesend until her death in 1659.

In the Battle of Brooklyn in August 1776, British soldiers landed in nearby Gravesend Bay. This area was built up following the completion of two subway lines, in 1915 (today’s N train) and 1919 (today’s F train).

On the accompanying map, note the four square blocks that are offset from the street grid. These formed the village of Gravesend. I approached this area from the Avenue U station on the N train. Avenue U is a busy street whose businesses reflect, and cater to, many nationalities. At the northwest corner of old Gravesend is a nondescript triangle with a monument to Deborah Moody. Perhaps the triangle looks better in spring or summer than in February.

Lady Moody Triangle.

Deborah Moody monument.

From there I walked along Village Road North to McDonald Avenue and turned right. McDonald Avenue and its elevated subway structure (F train) bisect old Gravesend. From McDonald Avenue I turned right onto Gravesend Neck Road, known familiarly as Neck Road. On the south side of the street is the entrance to Gravesend Cemetery.

From the NYC Parks website:

The cemetery occupies a 1.6-acre portion of one of the quadrants formed by the historic street grid. Lady Moody died in 1659 and is believed to be buried there in an unmarked grave. She is memorialized by a monument located near the front entry gate. Other early pioneer settlers of the area are also buried in the cemetery, as are several individuals noted for their roles in the Revolutionary War.

How did this site become parkland?

The cemetery expanded several times through the 18th and 19th centuries. It appears that its transition to municipal land started when a portion was deeded to the town in 1847 by Garret Stryker and his wife. In 1875, two additional parcels were transferred from Samuel G. Stryker and his wife Ellen Stillwell and Court J. Van Sicklen and his wife Catherine Johnson. The Van Sicklen family maintained their own cemetery, which accepted interments from 1847 to 1992, and bordered Gravesend Cemetery.

In 1903, NYC Mayor Seth Low conveyed the property to a group of trustees set up to manage the cemetery. By the 1940s, burials had ceased and the group had stopped submitting annual reports to the city and maintaining the property. At that time a series of city agencies were assigned to care for the site over several decades. Gravesend Cemetery and the Van Sicklen Cemetery were designated New York City Landmarks on March 23, 1976.

In 2003, the NYC Department of Citywide Administrative Services (DCAS) transferred Gravesend Cemetery, along with another eight cemeteries, to NYC Parks.

Old Gravesend Cemetery currently contains approximately 379 gravestones, which range in date from the mid-eighteenth century to the early twentieth century. The material of the headstones is diverse, and includes brownstone, slate, marble, fieldstone, cast iron, and other media. A rich complexity of carvings is also represented, with the earlier stones depicting winged cherubs while many nineteenth-century stones picture urns, willows, and other classical motifs. A valuable reflection of the history of the locality, some of the gravestones bear inscriptions in Dutch.

In 2019, the headstones were conserved by the NYC Parks Citywide Monuments Conservation Program with assistance from Green-Wood Cemetery, and Boy Scout Troops 22 and 237 installed benches, a path, and a flagpole. Parks reconstructed the park building’s roof, created an outdoor pavilion for programs, reconstructed the sidewalks and fences, and connected the Gravesend and Van Siclen Cemeteries.

Across Neck Road from the cemetery is the Lady Moody - Van Sicklen house. From the Historic Districts Council via urbanarchive.com:

The Lady Moody-Van Sicklen House is a rare surviving example of an 18th century Dutch-American farmhouse and a reminder of Brooklyn’s agricultural past. In addition to being one of the oldest houses in Brooklyn, it is also the borough’s only extant house of its age and type to be built of stone. While it is unlikely that any part of the house dates to her ownership of the property, the house sits on a lot once owned by Lady Deborah Moody, an English settler who founded Gravesend and one of the first women to be granted land in the New World. The house features a gable roof with overhanging eaves and an end chimney, typical features of 18th century Dutch-American farmhouses. It is one of only two extant houses that adhere to the original four-square plan laid out for the colonial town of Gravesend. This plan is unique in New York City, consisting of 16 acres per square, and is still visible in the modern street grid. The house is, therefore, integral to Gravesend’s history and identity. Subsequent owners included the prominent Van Sickles family and William E. and Isabella Platt, who renovated the house in the Arts and Crafts style in the early 20th century, and advertised its association with Lady Moody. The house was named a New York City landmark in April of 2016.

Lady Moody - Van Sicklen House.

Around the corner, off Van Sicklen Street, is a private cul-de-sac called Corso Court. The street sign is of the style put up all over Brooklyn in the 1950s.

Also on Van Sicklen Street is this gorgeous 19th-century house with an unfortunate modern front fence.

This was a short, easy walk on a chilly day but it was worth the effort, with a lot of historical significance. The walk itself is accessible but the two nearest subway stations, Avenue U on the F train and Avenue U on the N train, are not accessible. The B3 bus is accessible and runs frequently along Avenue U. It connects with many bus lines.

To JFK Airport and home again - accessibly

For the first time since my stroke in November 2018, I went from my home in Brooklyn to JFK airport entirely by public transportation, and a few days later went home from JFK the same way, rather than taking a taxi or car service. Local bus to Atlantic Terminal, Long Island Rail Road to Jamaica Station, JFK AirTrain to the terminal. From boarding the bus to the departure gate at the airport, the whole trip was accessible, and the process was smooth. Plus, it was decidedly less expensive: $1.45 for the bus, plus $5.00 for the LIRR, plus $8.50 for the AirTrain = $14.95 total each way.

I’m celebrating this as a not-so-small victory. I planned every leg of the trip in advance and allowed enough time that I was never in a hurry. I can do this and will do so again.

Onward!

Drumthwacket!

WHERE: Princeton, New Jersey

START/FINISH: Princeton station (New Jersey Transit Northeast Corridor line and Amtrak, then New Jersey Transit Princeton Shuttle), fully accessible

DISTANCE: 2.8 miles (4.5 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl except as noted.

Map of this walk, going clockwise from the Princeton station. Map courtesy footpathmap.com.

When the U.S. Mint began the 50 States quarter dollar series in 1999, the new quarters appeared in the order of their respective state’s accession to the Union. New Jersey was the second, and its design was one of the better ones. It bears the legend “Crossroads of the Revolution” and indeed New Jersey was, being situated between the largest city in the British colonies, Philadelphia, and New York.

Image courtesy PGCS CoinFacts.

Major military actions took place near Trenton (Washington crossing the Delaware River), Monmouth Court House (present-day Freehold), Morristown, and Princeton. Princeton has battle monuments, Princeton University, Albert Einstein’s house from when he was at Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study, and more.

All these would have made for a good trip, and the theme could have been Revolutionary Trails: Princeton. In 1681 William Penn purchased a large tract of land that includes present-day Princeton and its surrounds. Yet there is another thing about Princeton: the official residence of the governors of New Jersey, Drumthwacket. No, Drumthwacket is not an old-fashioned expletive, and it isn’t the name of a Charles Dickens character (think Hezekiah Drumthwacket). It’s a real place, visited on this walk.

This walk started at the Princeton railroad station, a 5-minute train ride from Princeton Junction on the Northeast Corridor. (Sidebar: Princeton Junction is an excellent place for trainspotting). Many mighty railroads are or were known by their initials: UP, PRR, and so on. The Princeton Shuttle, known locally as the Dinky, should be known as the PJ&B (Princeton Junction and Back).

I walked up a gentle hill past the Princeton Theological Seminary, founded in 1812.

Stuart Hall at Princeton Theological Seminary.

Passing the seminary, I turned onto Mercer Street heading toward no. 112, a simple frame house which Albert Einstein bought in 1936 and lived in for the rest of his life.

Albert Einstein’s house.

From there I walked up to Stockton Street (U.S. Route 206), which is the road to Trenton. It is a portion of the Colonial era King’s Highway from Newark to Philadelphia. After a short distance I came upon Drumthwacket. In 1697 William Olden purchased the land on which Drumthwacket stands.

Survey, dated 21 October 1696, of William Olden’s land purchase. Image courtesy The Drumthwacket Foundation.

In 1835 a descendant of William Olden, Charles Smith Olden, who gained his wealth in business ventures in New Orleans and an inheritance from an uncle, began construction of Drumthwacket in 1835. According to The Drumthwacket Foundation:

For its name, Drumthwacket was the estate of a hero in one of Sir Walter Scott’s popular historical novels, A Legend (of the Wars) of Montrose, published in 1819. It is believed that Governor Olden gave his new house this Scots-Gaelic name (which means “wooded hill”) upon reading the book. The original structure consisted of the center hall with two rooms on each side in addition to the large portico with detailed Ionic columns.

Drumthwacket seen from across Stockton Street.

Unfortunately, Drumthwacket was not open to the public this day, and the sidewalk is on the opposite side of Stockton Street. It has been the official residence of the governors of New Jersey since 1982 but is not lived in by the current governor, Phil Murphy. It is maintained by The Drumthwacket Foundation, whose website, https://drumthwacket.org/, has plenty of information about the history of the house and current programs there.

Walking back into town, I passed several splendid houses.

217 Stockton Street.

The Present Day Club, founded in 1898.

Near the beginning of Stockton Street is Morven, built in the 1750s by Richard Stockton (1730 - 1781), a signer of the Declaration of Independence whose land grant in Princeton led the College of New Jersey to move there from Newark in 1756. The College of New Jersey is now Princeton University. The house remained in Stockton family ownership until 1944, when it was purchased by New Jersey Governor Walter E. Edge. The sale was subject to the condition that Morven would be given to the state of New Jersey within two years of Edge's death. Edge transferred ownership of Morven to the state during 1954, several years before he died. Morven was the official residence of the governors of New Jersey from 1944 until 1981. The house is now a museum.

Morven.

A bit farther on is the Princeton Battle Monument.

Across Stockton Street from the Princeton Battle Monument is the stately Trinity Church (Episcopalian). From the church’s website:

Founded in 1833 by a group of local families, including architect and churchwarden Charles Steadman who built a stick-framed Greek Revival meeting hall for the congregation. Over the next forty years, Trinity prospered and in 1870 the original structure was replaced by a stone Gothic Revival church designed by architect Richard Upjohn. In the first two decades of the 20th century, architect Ralph Adams Cram was hired twice, first doubling the nave in length and later creating a small chapel in the north transept, a larger French Gothic chancel, and a significantly heightened tower accommodating a small carillon of ten Meneely bells. With some interior alterations, this is the church as it is today.

From there I walked down University Avenue toward the train station, not quite making it as I tripped and fell, and was taken to the emergency room at Princeton Medical Center. Fortunately the damage is not too serious, the worst of it being on my right knee. But I’ll be back walking soon and will definitely return to Princeton, as there is much more to take in.

Holiday display in front of a house on University Avenue. Moose in Princeton!

Revolutionary Trails: Morristown

The Washington Headquarters Museum.

WHERE: Morristown, New Jersey

START/FINISH: Morristown station (New Jersey Transit Morris and Essex Line), accessible

DISTANCE: 2.4 miles (3.9 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl. Map courtesy footpathmap.com.

Map of this walk. Route clockwise from the train station.

Most of my walks have a theme such as stair streets, architecture, walkable bridges, and so on. A few of my walks will include sites from the American Revolution. This walk, in Morristown, New Jersey, started the series. Others will be in White Plains, Princeton, Brooklyn, and more.

Morristown is a pleasant, prosperous-looking town, the county seat of Morris County. The walk began at the Morristown station, accessible with a mini-high platform in either direction and an elevator on the westbound platform. The Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad, a precursor to New Jersey Transit, built impressive stations and other infrastructure throughout its territory. The Morristown station, dating from 1913, is no exception.

Leaving the station, my first stop was the Schuyler - Hamilton House Museum, built as the Campfield House around 1760. The second image below describes it. The house is maintained by the local chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution and it is open to the public only on Sunday afternoons.

From there I went to the Washington Headquarters Museum. This building was George Washington’s headquarters from December 1779 until June 1780. It was the harshest winter ever recorded. Washington chose Morristown not by accident. It was near enough to British-occupied New York (about 30 miles/50 kilometers) to keep an eye on what was going on there, yet far enough away to have some protection afforded by distance and the Watchung Mountains. The museum has many interesting historical artifacts and a short film that is helpful with the context of the site, and is open Thursdays through Sundays. The museum is accessible from the parking lot on Washington Street.

The quotation seems sadly appropriate to our time.

George and Martha Washington lived in the Ford House, across from the headquarters.

Officers of lower rank, and ordinary soldiers, built an encampment of log huts at Jockey Hollow, south of town, during that harsh winter. Jockey Hollow is not accessible by public transportation but I’ll find a way to get there on a future visit.

For a lot more information about the Morristown National Historical Park, go to https://www.nps.gov/morr/index.htm

From Washington’s headquarters I meandered through town toward the town green. Within a few blocks I passed old houses, new houses, two Episcopalian churches, a Presbyterian church, and a Roman Catholic church. Walking along Franklin Street, I had a nice chat with a homeowner who was raking leaves in front of his house. South Street has a lot of shops and restaurants.

St. Peter’s Episcopal Church.

Church of the Redeemer (Episcopalian)

South Street, looking west.

The Vail Mansion, once the town hall, and a monument to Morristown’s World War I dead.

The Presbyterian Church of Morristown, on the town green.

The town is quite walkable, but it has its challenges for accessibility, with many short slopes and stretches of uneven sidewalk, the latter reminding me of my neighborhood in Brooklyn. Walking from the train station to Washington’s headquarters takes one past an unsignaled left turn onto Interstate 287, so look carefully before crossing! As the train station has only mini-high platforms, not full-length high platforms, be in the first open car on the train in either direction.

Morristown has a lot more history than I could absorb in an afternoon, so I’ll go back. It’s an easy train ride from New York or Hoboken, around 1 hour 20 minutes. And it is pleasant to walk around.

Two More Harlem River Bridges (Bronx and Manhattan)

WHERE: The Washington Bridge and the Broadway Bridge, both between the Bronx and Manhattan

START: 170 Street subway station (4 train), fully accessible

FINISH: 231 Street subway station (1 train), fully accessible

DISTANCE: 4.5 miles (7.2 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl except as noted. Map courtesy Google Maps.

Route of this walk, reading from bottom to top.

Before this walk I had walked all the walkable bridges across the Harlem River except two: the Washington Bridge (not to be confused with the George Washington Bridge over the Hudson River) and the Broadway Bridge. I decided to cross both of them in the course of one walk, which was the longest walk I had done for some time, on a clear, crisp Saturday afternoon. This included a good climb at the start along Macombs Road and the charmingly named Featherbed Lane. For some history of Featherbed Lane see the post entitled “West Bronx Mix 2” on the “Stair Streets” page. I’ve previously tackled many stair streets in this part of the Bronx.

A short distance into the walk was this apartment building, 1460 Macombs Road, with nice details.

From that apartment building almost to the Washington Bridge, the route was a steady, sometimes steep, uphill, but the climb was bracing.

The Washington Bridge opened in 1888, linking University Avenue in the Bronx and West 181 Street in Manhattan. At first it had two wide sidewalks; now, the sidewalks are not wide enough for two people to pass. I had to back up to the fence to allow people to pass. I’m glad to see that one of the Manhattan-bound car lanes has been converted to a bi-directional bike path.

Washington Bridge, circa 1900. Image courtesy Columbia University Libraries.

Washington Bridge, looking toward the Bronx. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

Washington Bridge, looking toward Manhattan.

The chain link fence is understandable but a bit depressing. Still, I was able to get a view up the Harlem River showing the fall colors.

At the Manhattan end of the bridge is McNally Plaza, with a monument to neighborhood residents who died in the World War (World War I, that is).

I walked north on Laurel Hill Terrace, abutting Highbridge Park and its steep drop toward the Harlem River.

At West 184 Street I noticed what looked like well-maintained stairs going down to the Highbridge Park footpath. I’m going back there.

When i got to St. Nicholas Avenue and West 190 Street, I had the choice of going to and down the very steep street called Fort George Hill, or taking the elevator down to the 3-block long tunnel street to Broadway. For me, walking downhill without a handrail is more challenging than walking uphill without a handrail. I chose the elevator and tunnel street, which link to the deepest subway station in the city, the 191 Street station (1 train). The tunnel was recently and somewhat controversially rehabilitated to cover over the graffiti and open the surfaces to local artists. The graffiti is starting to return. At the Broadway entrance to the tunnel is a set of stairs next to a ramp that is too steep for wheelchairs, pedestrians, or much else.

What were they thinking?

At Broadway I began the second part of this walk, through the Inwood neighborhood to the Broadway Bridge. Walking along Sherman Avenue, I was in the heart of a vibrant community of people with roots in the Dominican Republic. I saw a lot of businesses offering money transfer and shipping services, the latter for people to send appliances and other things “back home.” I saw men playing dominoes at a table on the sidewalk. Sickles Street is co-named Santiago Cerón Way, for the Dominican singer who lived from 1940 to 2011. Sickles Street is named for the Sickles family, which once owned a tract of land in this area.

And there’s this establishment at Sherman Avenue and West 207 Street. Mofongo, piano bar, bakery, sushi. They have it all. I should try it.

While in this area I was interested to see if there were any sign, even a historical marker, noting the Inwood African Burial Ground that was on 10 Avenue between West 211 and West 212 Streets. Sadly, there is none. From the Dyckman Farmhouse Museum Alliance’s website:

In March of 1903, various New York City headlines announced the discovery of rows of skeletons under unmarked stone markers during construction that revealed a slave cemetery. City contractors ultimately destroyed the site to continue leveling the ground for urban development. The remains were quickly analyzed by amateur archaeologists before the bones were first left uncollected, then discarded. Today, no sign of it as a cemetery remains except in historical records. … This block is currently occupied by various Auto Shops and P.S. 98 - Shorac Kappock’s faculty parking lot.

I walked up West 212 Street to Broadway, where I turned north. I soon came upon the place where I started my climbing of New York City’s stair streets, at West 215 Street. This stair street was one of many personal triumphs recorded on this blog.

Soon I passed Columbia University’s Wien Stadium and came within sight of the Broadway Bridge.

The present Broadway Bridge is a vertical lift span that opened in 1962, replacing a swing bridge dating from 1906. The bridge has a lower deck for motor vehicles, bicycles, and pedestrians and an upper deck for the subway, as the 1906 bridge did. The bridge spans what was called the Harlem Ship Canal, built in the late 19th century to facilitate navigation on the Harlem River, in place of the winding Spuyten Duyvil Creek. An excellent history of this area, and the bridges preceding the Broadway Bridges, may be found at https://www.welcome2thebronx.com/2018/08/02/in-search-of-the-historic-kings-bridge-on-the-bronx-manhattan-border/.

Broadway Bridge. Image from flickr.com.

View from the Broadway Bridge to Marble Hill and the Marble Hill station of Metro North Railroad’s Hudson Line.

From here I walked north on Broadway to the elevated 231 Street subway station, following lunch.

On this walk, not only did I cross the two bridges I intended to, I saw a lot of interesting things and imagined others, where there was no trace of what came before. The steady uphill to the Washington Bridge was a good workout. All this on a picture-perfect day.

Shoelace Park (Bronx)

WHERE: The Bronx River Park Reservation between East 233 Street and East Gun Hill Road, known as Shoelace Park

START: Woodlawn station (Metro North Railroad, Harlem Line)

FINISH: Gun Hill Road subway station (2 train), fully accessible

DISTANCE: 1.5 miles (2.4 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl. Map courtesy footpathmap.com

Route of this walk, reading from top to bottom.

This was a sequel to the walk I described in the post on this page entitled “Bronx Park,” taking in a long, narrow green space sandwiched between the Bronx River on the west and Bronx Boulevard on the east. Shoelace Park is the name given it by that amazing organization. the Bronx River Alliance. This walk started at the Woodlawn railroad station, across from the famous Woodlawn Cemetery. That cemetery deserves, and will get, its own walk. From the top of the stairs at the railroad station, turn left and walk over the Bronx River Parkway and the Bronx River. The river, though it is hemmed in by the city, looks idyllic.

The Bronx River, looking upstream from East 233 Street.

At the first crosswalk, turn right to cross East 233 Street onto the park path. The path crosses the ramp to the parkway, and just beyond the path divides. Bear to the left; this will take you to the Bronx River Greenway. It is in far better condition than the park paths closer to the river.

At approximately East 225 Street is this monument to William White Niles (1861 - 1935). The plaque reads “To record the fact that William White Niles was the founder of the Bronx River Parkway, this memorial has been erected by his friends.” According to the NYC Parks website:

In 1881, Niles helped found the New York Park Association. The Association presented comparative studies of parkland in foreign cities, predictions of rapid population growth in New York, and rising land values in a call for more parkland in the Bronx, which was annexed by New York City in 1874. This effort culminated in the 1884 New Parks Act and the city’s 1888-90 purchase of lands for Van Cortlandt, Claremont, Crotona, Bronx, St. Mary’s, and Pelham Bay Parks and the Mosholu, Pelham, and Crotona Parkways. The new properties increased the city’s parkland fivefold, from about 1,000 acres to about 5,000 acres.

Niles continued to strive for the development of Bronx parkland along the Bronx River. The 23-mile river had been greatly contaminated, and Niles was one of many that called for a solution to protect the quality of Bronx Park. The Bronx River Sewer Commission was established in 1905 and the Bronx River Parkway Commission was created in 1906 to reduce the sewage and beautify the edge of the river. Niles, a Bronx resident, served as the vice-president of the Bronx River Parkway Commission from 1907 to 1925. The commission sought the acquisition of land along the river, and the long process was hailed as a success when the Bronx River Parkway opened in 1925.

Niles’ legacy lives on through the efforts in this century by those of the Bronx River Alliance, the City of New York, and Westchester County.

Much of Shoelace Park occupies the original alignment of the Bronx River Parkway. From the Bronx River Alliance website:

The roadbed of the main pathway in the park is the site of a portion of the original Bronx River Parkway. The Bronx River Parkway was completed in 1925 and was seen as both a site for leisure driving and a critical connection from the city to the country. However, shortly after the parkway was completed, its design became obsolete due to advances in automobile technology that made cars too fast for the narrow and curved road. In 1950 the portion of the parkway that is now Shoelace Park was relocated from Bronx Boulevard to where it currently stands, adjacent to [and across] the Bronx River. The original roadbed remained in place and serves as the upper path in the park.

The former life of Shoelace Park is hinted at by this photograph.

On my walk I passed by picnickers and a church youth group. Besides the park paths, there are benches, a basketball court, a comfort station, and a kayak launch. Here’s a fun video about kayaking on this portion of the Bronx River:

The Bronx River Alliance has installed simple but effective signage in Shoelace Park, two examples of which are below. Signs similar to that in the second image should point the way to the Gun Hill Road, 225 Street, and 233 Street subway stations, and to the Woodlawn and Williams Bridge railroad stations.

At East 211 Street I exited the park to make my way to East Gun Hill Road and the subway.

Bronx Boulevard’s grand name belies the fact that for most of its length it is a narrow neighborhood street. The buildings along it are detached houses, attached houses, apartment buildings, and a hospital. One apartment building caught my eye for its late Art Deco ornamentation.

This walk was easy and, except for the stairs from the Woodlawn railroad station to the street. was fully accessible. Though I was never far from the sound of trains or traffic on the Bronx River Parkway, this is a thoroughly enjoyable green space, well worth the travel from where I live in Brooklyn. I saw at least four abandoned CitiBikes in the park; the CitiBike folks should rescue and repair these, and get them back on the streets where they belong.

Bit by bit I’m walking the Bronx River Greenway in the Bronx and I’ll tackle the paths along the Bronx River in Westchester County.

Flushing Loop (Queens)

WHERE: The central part of Flushing, Queens

START/FINISH: Main Street Flushing subway station (7 train), fully accessible. Also reached by Flushing Main Street station (Long Island Rail Road Port Washington Branch), fully accessible, and numerous bus routes.

DISTANCE: 2.25 miles (3.6 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl except as noted. Map courtesy footpathmap.com.

Flushing is a bustling community in central Queens. Just to the west are Flushing Meadow - Corona Park (site of the 1939 - 1940 and 1964 - 1965 World’s Fairs), the U.S. National Tennis Center (site of the U.S. Tennis Open), and Citi Field (home of the New York Mets). La Guardia Airport is nearby. As Kevin Walsh wrote in his excellent book Forgotten New York:

The land just east of the Flushing River in the center of Queens had been occupied for many centuries by the Matinecock Indians, then by Dutch and English settlers, and later by waves of immigrants, all of whom have put their own particular stamp on the neighborhood.

As recently as the 1950s and 1960s, Flushing was a sleepy town of old-timey Victorian homes protected by shade trees, with a lively downtown centered on Main Street between Northern Boulevard and the Long Island Rail Road Port Washington line. A slow trickle of immigrants from eastern Asia has revitalized the region, but at the cost of its old-fashioned atmosphere as the old Victorian structures were torn down and high-rise apartment buildings and attached houses replaced them.

To be sure, a fair amount of the former Flushing remains, just not in its central core. On this walk I wanted to see historically significant structures in central Flushing, and, of course, have a good lunch at the end, all on an accessible walk.

Main Street, looking north toward Roosevelt Avenue, 1923. Image courtesy New York Transit Museum by way of urbanarchive.org. The subway opened at this intersection in 1927.

Main Street, looking south toward Roosevelt Avenue, 2024.

Route of this walk, reading clockwise from bottom.

Flushing was established as a settlement of New Netherland on October 10, 1645, on the eastern bank of Flushing Creek. It was named Vlissingen, after the Dutch city of Vlissingen. The English took control of New Amsterdam in 1664, and when Queens County was established in 1683, the Town of Flushing was one of the original five towns of Queens.

Flushing played an important role in the establishment of religious liberty in the New World. From Wikipedia:

Unlike all other towns in the region, the charter of Flushing allowed residents freedom of religion as practiced in Holland "without the disturbance of any magistrate or ecclesiastical minister". However, in 1656, New Amsterdam Director-General Peter Stuyvesant issued an edict prohibiting the harboring of Quakers. On December 27, 1657, the inhabitants of Flushing approved a protest known as the Flushing Remonstrance. This petition contained religious arguments even mentioning freedom for "Jews, Turks, and Egyptians," but ended with a forceful declaration that any infringement of the town charter would not be tolerated. Subsequently, a farmer named John Bowne held Quaker meetings in his home and was arrested for this and deported to Holland. Eventually he persuaded the Dutch West India Company to allow Quakers and others to worship freely.

For a fuller discussion of the importance of the Flushing Remonstrance see https://www.nytimes.com/2007/12/27/opinion/27jackson.html. View the text of the Flushing Remonstrance at https://history.nycourts.gov/about_period/flushing-remonstrance/#:~:text=Full%20Text%20of%20the%20Flushing%20Remonstrance%20You%20have,to%20be%2C%20by%20some%2C%20seducers%20of%20the%20people. The importance of this document in American history, and its relevance to the present day, cannot be overstated.

Starting at the busy Main Street subway station, which is the end of the 7 train, I walked north on Main Street. On the west side between 39 Avenue and 38 Avenue is St. George’s Episcopal Church, dedicated in 1854. One of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, Francis Lewis, was a vestryman of this congregation. Somehow this church has survived the cacophony of Main Street. The church offers Sunday services in English, Spanish, and Mandarin.

I continued north on Main Street and turned right onto busy Northern Boulevard (New York Route 25A). Northern Boulevard starts a few blocks from the 59 Street Bridge in Long Island City, goes all the way across Queens, and runs well into Nassau County. The section starting in Flushing was once the Flushing and Bayside Plank Road, later Broadway. Just east of Northern Boulevard is the Friends Meeting House, in continuous use for Quaker services since it was built in 1694 (except during the American Revolution).

Across Northern Boulevard from the Friends Meeting House is the Flushing Town Hall (1862). According to Kevin Walsh, this beautiful building was constructed by a local carpenter. This was seat of government for the Town of Flushing until the western towns of Queens County became part of New York City in 1898. An early speaker at the Town Hall was Frederick Douglass. The eastern towns formed Nassau County. It is now the seat of the Flushing Council on Culture and the Arts and is home to many arts programs.

From the Town Hall I walked east on Northern Boulevard and turned left onto Leavitt Street, toward my next stop, the Lewis Latimer house. Latimer (1848 - 1928), inventor and engineer, was born to previously enslaved parents. He was an assistant to Alexander Graham Bell and later, according to Kevin Walsh,

… [produced] a long-lasting carbon filament that was a major improvement on Edison’s 1878 electric lightbulb. Latimer also developed the first threaded lightbulb socket and assisted in the installation of New York City’s first electric streetlamps.

Latimer’s house was moved to its present location after being landmarked in 1995 and restored.

Lewis Latimer house with Latimer (center) on the porch. Image courtesy Historic House Trust by way of urbanarchive.org.

Lewis Latimer house today.

From there I crossed Leavitt Street and walked east on 34 Avenue, then turned right onto Union Street. At Northern Boulevard, seemingly marooned in the wide median, is Flushing’s World War I memorial.

The crosswalk here crosses westbound Northern Boulevard at an angle. Don’t take your time crossing and don’t expect to cross the eastbound lanes on the same signal. Once all the way across Northern Boulevard, I crossed Union Street and walked uphill on Northern Boulevard to Bowne Street, where I turned right. One block on, on the left side of the street, is a playground and park called the Margaret I. Carman Green. From the New York City Parks website:

Situated in Weeping Beech Park, this plot was named in memory of Margaret I. Carman in 1976. A Flushing native, Carman taught at Flushing High School, which is located across the street, for 44 years. Established in 1875, Flushing High School is the oldest public secondary school in New York City.

Margaret Carman was born on July 12, 1890 to a prominent family rich in history. Her father, Ringgold W. Carman was a member of the Union Army, and a descendant of Revolutionary War hero Captain Henry “Lighthouse Harry” Lee and relative of his legendary son, Confederate General Robert E. Lee (1807-1870). Margaret Carman graduated from St. Joseph’s Academy for Young Ladies, Flushing High School, and Barnard College. She was a lifelong member of the Daughters of the American Revolution. After retiring from her teaching career at Flushing High School in 1960, Carman devoted herself to propagating and maintaining Flushing’s abundant history.

The green is on part of the site of the Parsons Nursery. From the Bowne House website (link below):

Samuel Parsons (1774 - 1841) joined the Bowne family of Flushing when he married Mary Bowne in 1806. Samuel was a Quaker minister and a farmer. Samuel and Mary owned property near the 1661 Bowne homestead to the north and east of Bowne House. Samuel acquired trees and shrubs with the intention of establishing a nursery to pass on to his sons upon his death. That land became the well-known Parsons Nursery.

Samuel refused to own slaves and served as clerk of the New York Meeting. In 1834, he wrote a letter to a Joseph Talcott advising that the New York Meeting had raised over $1000 to move up north free Southern blacks who were being threatened with a return to slavery. Samuel also signed as clerk a long denunciation of slavery issued by the New York Yearly Meeting in June 1837. He wrote about his anti-slavery views in his letters and had friends and colleagues who were abolitionists.