Another Stop on the Trail of Religious Liberty

WHERE: The Gravesend neighborhood of Brooklyn.

Photographs by Michael Cairl.

Map of Gravesend, courtesy Open Street Maps.

What is now New York City became home to two women for whom the Puritans of the Massachusetts Bay Colony had no use. Leading bands of religious dissenters was bad enough, but having them led by women must have been more than the Puritans could stand. These women were Anne Hutchinson (1591 - 1643), who fled to what is now the Bronx, and Deborah Moody (1586 - 1659), who founded the community of Gravesend in the part of New Netherland now known as Brooklyn. I’ve wanted to walk around Gravesend for some time, and a typically excellent and fun video by Tom Delgado (featured at the end of this post) was all I needed to get going. So I picked a cold February day to go there.

From the website of New York Historical (also known as the New-York Historical Society):

Deborah Dunch was born in London, England in 1586. She was the daughter of Walter Dunch, the auditor of the Royal Mint, and his wife, Deborah. Her ancestors were loyal supporters of the British monarchy and the Church of England. She married Sir Henry Moody in 1606, becoming Lady Deborah Moody.

After the death of her husband in 1629, Deborah became an Anabaptist. The Anabaptists were a Protestant sect of Christianity who believed that baptism should not occur until a person was old enough to consent. In England, where the Church of England was headed by the king, Anabaptists were considered a danger to the stability of the nation. Women in particular were vilified for following this religion. When word of her new beliefs got out, Deborah was summoned to appear in court. Rather than face whatever punishment the government had in mind, Deborah gathered her wealth and set sail for the English colonies in North America. She was fifty-four when she arrived in Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1639. The colony was run by Puritans, another Protestant sect that had been forced to flee England. Deborah probably chose it thinking it would be a place where she could practice her beliefs in peace.

The Massachusetts Bay Colony was not the haven of tolerance that Deborah hoped for. Deborah originally settled in the town of Saugus, Massachusetts, before moving to a large farm in Swampscott, just outside of Salem. She conducted a lively correspondence with other people in the area who were not Puritans. This drew the attention of her closest neighbor, Reverend Hugh Peter. Hugh believed that the Massachusetts colony should have religious unity. He had already expelled another Anabaptist woman, Anne Hutchinson, two years prior to Deborah’s arrival. In 1643 Deborah was brought before the court for spreading religious dissent. During her trial, Puritan leader John Endecott described her as a “dangerous woman.” She was given the choice to change her beliefs or be excommunicated from the colony. Deborah chose excommunication, gathered her fellow Anabaptists, and set out once again to find a place where they could practice their religion in peace.

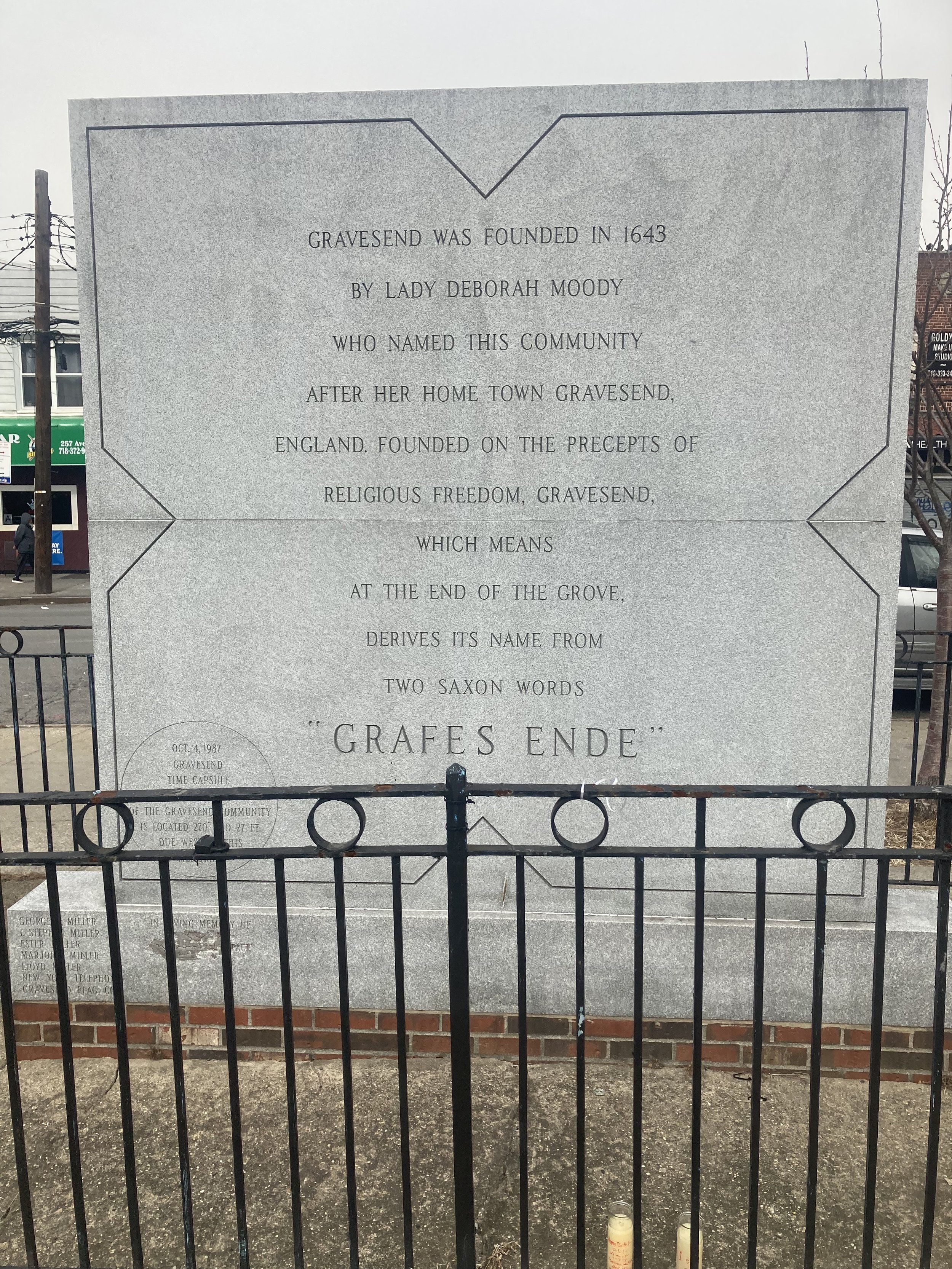

Deborah drew up the plans for her new community and named it Gravesend. It was the first New World settlement founded by a woman.

At the same time that Deborah was standing trial in Massachusetts, Director Willem Kieft of the Dutch West India Company was looking to recruit new settlers to the New Netherland colony. Willem had recently started a war with local Mohawk communities and wanted to increase the colony’s population to make it harder for the Mohawk to take back their land. Deborah was a woman with money who already had followers willing to help settle a new community. The Netherlands and its colonies practiced a greater degree of religious tolerance than England and Massachusetts, so Anabaptist beliefs were less worrisome there. Willem granted Deborah the southwestern tip of Long Island, territory that now encompasses parts of Bensonhurst, Coney Island, Brighton Beach, and Sheepshead Bay in Brooklyn.

Deborah drew up the plans for her new community and named it Gravesend. It was one of the first settlements in the American colonies founded by a woman. She allowed the inhabitants of Gravesend to follow whatever religious practices they chose, so long as they abided by the laws of the colony. Gravesend was targeted by local Native American communities who were angry with the Dutch colonists settling their land. This was no minor threat—in 1643 another outlying settlement in New Netherland was destroyed because of the ongoing conflict. In spite of these very real dangers, Deborah and her followers chose to stay.

As Deborah’s community grew, so did her influence in the government of New Netherland. In 1647 she was among the colony’s elite who greeted the new Director-General Peter Stuyvesant. In 1654 Peter called on her to mediate a tax dispute, and in 1655 she was called upon to nominate magistrates for Gravesend. Deborah lived in Gravesend until her death in 1659.

In the Battle of Brooklyn in August 1776, British soldiers landed in nearby Gravesend Bay. This area was built up following the completion of two subway lines, in 1915 (today’s N train) and 1919 (today’s F train).

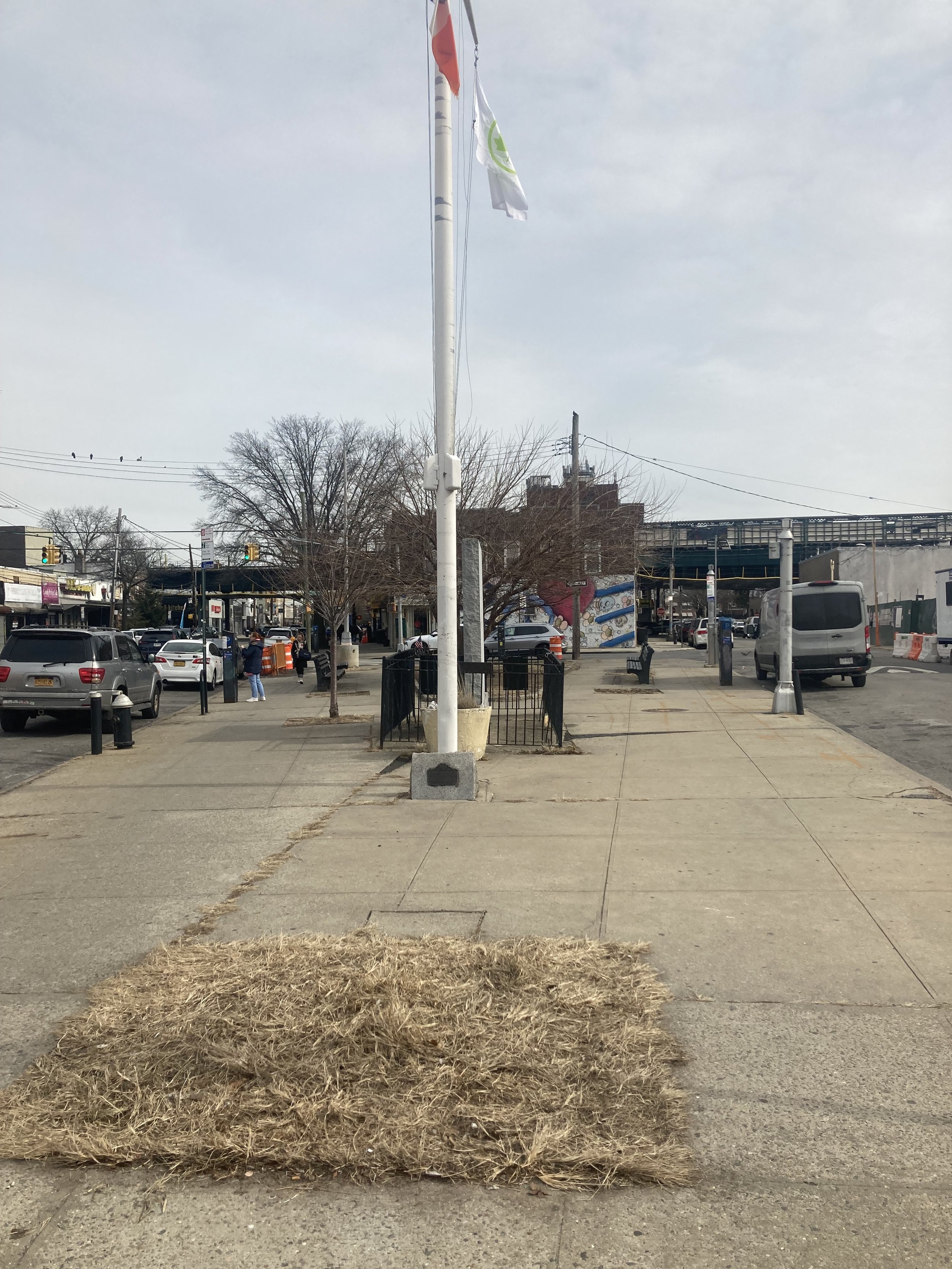

On the accompanying map, note the four square blocks that are offset from the street grid. These formed the village of Gravesend. I approached this area from the Avenue U station on the N train. Avenue U is a busy street whose businesses reflect, and cater to, many nationalities. At the northwest corner of old Gravesend is a nondescript triangle with a monument to Deborah Moody. Perhaps the triangle looks better in spring or summer than in February.

Lady Moody Triangle.

Deborah Moody monument.

From there I walked along Village Road North to McDonald Avenue and turned right. McDonald Avenue and its elevated subway structure (F train) bisect old Gravesend. From McDonald Avenue I turned right onto Gravesend Neck Road, known familiarly as Neck Road. On the south side of the street is the entrance to Gravesend Cemetery.

From the NYC Parks website:

The cemetery occupies a 1.6-acre portion of one of the quadrants formed by the historic street grid. Lady Moody died in 1659 and is believed to be buried there in an unmarked grave. She is memorialized by a monument located near the front entry gate. Other early pioneer settlers of the area are also buried in the cemetery, as are several individuals noted for their roles in the Revolutionary War.

How did this site become parkland?

The cemetery expanded several times through the 18th and 19th centuries. It appears that its transition to municipal land started when a portion was deeded to the town in 1847 by Garret Stryker and his wife. In 1875, two additional parcels were transferred from Samuel G. Stryker and his wife Ellen Stillwell and Court J. Van Sicklen and his wife Catherine Johnson. The Van Sicklen family maintained their own cemetery, which accepted interments from 1847 to 1992, and bordered Gravesend Cemetery.

In 1903, NYC Mayor Seth Low conveyed the property to a group of trustees set up to manage the cemetery. By the 1940s, burials had ceased and the group had stopped submitting annual reports to the city and maintaining the property. At that time a series of city agencies were assigned to care for the site over several decades. Gravesend Cemetery and the Van Sicklen Cemetery were designated New York City Landmarks on March 23, 1976.

In 2003, the NYC Department of Citywide Administrative Services (DCAS) transferred Gravesend Cemetery, along with another eight cemeteries, to NYC Parks.

Old Gravesend Cemetery currently contains approximately 379 gravestones, which range in date from the mid-eighteenth century to the early twentieth century. The material of the headstones is diverse, and includes brownstone, slate, marble, fieldstone, cast iron, and other media. A rich complexity of carvings is also represented, with the earlier stones depicting winged cherubs while many nineteenth-century stones picture urns, willows, and other classical motifs. A valuable reflection of the history of the locality, some of the gravestones bear inscriptions in Dutch.

In 2019, the headstones were conserved by the NYC Parks Citywide Monuments Conservation Program with assistance from Green-Wood Cemetery, and Boy Scout Troops 22 and 237 installed benches, a path, and a flagpole. Parks reconstructed the park building’s roof, created an outdoor pavilion for programs, reconstructed the sidewalks and fences, and connected the Gravesend and Van Siclen Cemeteries.

Across Neck Road from the cemetery is the Lady Moody - Van Sicklen house. From the Historic Districts Council via urbanarchive.com:

The Lady Moody-Van Sicklen House is a rare surviving example of an 18th century Dutch-American farmhouse and a reminder of Brooklyn’s agricultural past. In addition to being one of the oldest houses in Brooklyn, it is also the borough’s only extant house of its age and type to be built of stone. While it is unlikely that any part of the house dates to her ownership of the property, the house sits on a lot once owned by Lady Deborah Moody, an English settler who founded Gravesend and one of the first women to be granted land in the New World. The house features a gable roof with overhanging eaves and an end chimney, typical features of 18th century Dutch-American farmhouses. It is one of only two extant houses that adhere to the original four-square plan laid out for the colonial town of Gravesend. This plan is unique in New York City, consisting of 16 acres per square, and is still visible in the modern street grid. The house is, therefore, integral to Gravesend’s history and identity. Subsequent owners included the prominent Van Sickles family and William E. and Isabella Platt, who renovated the house in the Arts and Crafts style in the early 20th century, and advertised its association with Lady Moody. The house was named a New York City landmark in April of 2016.

Lady Moody - Van Sicklen House.

Around the corner, off Van Sicklen Street, is a private cul-de-sac called Corso Court. The street sign is of the style put up all over Brooklyn in the 1950s.

Also on Van Sicklen Street is this gorgeous 19th-century house with an unfortunate modern front fence.

This was a short, easy walk on a chilly day but it was worth the effort, with a lot of historical significance. The walk itself is accessible but the two nearest subway stations, Avenue U on the F train and Avenue U on the N train, are not accessible. The B3 bus is accessible and runs frequently along Avenue U. It connects with many bus lines.