Bronx Park

WHERE: A portion of Bronx Park

START: Botanical Garden station (Metro North Railroad, Harlem Line), fully accessible, also Bx26 bus

FINISH: Gun Hill Road subway station (2 train), fully accessible; also Bx39, Bx41 buses

DISTANCE: 1.5 miles (2.4 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl except as noted. Map courtesy footpathmap.com.

Route of this walk, reading from left to right.

On a map Bronx Park appears roughly as a triangle, much of the lower part taken up by the Bronx Zoo and the New York Botanical Garden, adjoining the Rose Hill campus of Fordham University. There is still much of it that is just a public park. On this walk we will traverse the northern part of Bronx Park.

The Bronx River runs north to south through the park. Through the efforts of the Bronx River Alliance the Bronx River Greenway is being created and the Bronx River is being cleaned up and made open to the public. This walk takes us along a portion of the Bronx River Greenway, including a crossing of the Bronx River. Other walks on this site cover other portions of the Greenway.

Part of this walk also takes us through the Bronx River Parkway Reservation. The Bronx River Parkway Reservation is a linear park that includes recreational facilities, preserved and restored natural areas, and a road that is restricted to private passenger vehicles. The Reservation parallels the Bronx River for 15.5 miles (25 kilometers) from the New York Botanical Garden north to Kensico Dam at Valhalla in Westchester County. The parkway extends 12.5 miles (20 kilometers) in Westchester County and its original section, from the New York City limits south to Burke Avenue, another 3 miles (5 kilometers). According to the Historic American Enginering Record:

The Bronx River Parkway Reservation was the first public parkway designed explicitly for automobile use. The project began as an environmental restoration and park development initiative that aimed to transform the heavily polluted Bronx River into an attractive linear park connecting New York City’s Bronx Park with New York City’s Kensico Dam and reservoir. With the addition of a parkway drive the project became a pioneering example of modern motorway development. It combined beauty, safety, and efficiency by reducing the number of dangerous intersections, limiting access from surrounding streets and businesses, and surrounding motorists in a broad swath of landscaped greenery.

In addition to reclaiming the Bronx River, the Bronx Parkway Commission (BPC), as it was called, cleaned each parcel of land as soon as it acquired title. The BPC immediately instituted a forestry program. “The condition of the trees in this section of the country,” the BPC noted, was “cause for grave concern.” Prompt measures were necessary.

The BPC hired a forester, Albert N. Robson, who was noted for his experience in tree care. In addition, the commission engaged Hermann Merkel, a landscape architect and forester at the Bronx Zoo and Botanical Gardens, who was considered to be a recognized authority on various tree pests. Robson’s and Merkel’s first year with the commission resulted in 13,018 dead trees being removed, 5,037 trees trimmed, and 16,039 trees improved and reclaimed by surgery.

Construction of the Bronx River Parkway began in 1908. It was completed as far south as Burke Avenue in 1925 and the extension to Story Avenue in the south central Bronx opened in 1951.

I started the walk on this picture-perfect Memorial Day at the Botanical Garden railroad station, across the street from the New York Botanical Garden. The Botanical Garden is worth its own blog post at the very least. From there I walked north on the footpath that parallels Southern Boulevard, crossed Mosholu Parkway, and continued north on the path, following the Bronx River Greenway/East Coast Greenway arrow.

Going left at the arrow and continuing past baseball fields on the right, I passed French Charley’s Playground. Who exactly was French Charley? The NYC Parks website has the answer: “This playground honors the memory of Charley Mangin who owned a nearby French restaurant in the 1890s. His establishment, in the heart of a small French enclave of the Bronx, was popularly referred to as French Charley’s. After the restaurant closed down, a ball field and picnic area were built near the site and people began to refer to the site as French Charley’s Field.” This has become a playground and picnicking area.

From there I continued on the path, following the arrows, through the Bronx River Forest, a remnant of the original forests and floodplains that once blanketed the Bronx River corridor. The path crosses the Bronx River on the Burke Avenue Bridge, then ducks underneath the Bronx River Parkway.

Path through the Bronx River Forest.

Bronx River Parkway underpass.

Past the Parkway I turned left, and across from the Rosewood Playground was a stone monument. The near (south) side is missing a plaque that was engraved thus and memorializes the huge undertaking that was the construction of the Bronx River Parkway, not just the road of that name.

BRONX RIVER PARKWAY/PLANNED AND BUILT BY THE/BRONX PARKWAY COMMISSION/ESTABLISHED 1907 AND APPROVED 1913/WITH FIRST APPROPRIATION BY THE/CITY OF NEW YORK/AND THE/COUNTY OF WESTCHESTER/COMPLETED 1925/MADISON GRANT PRESIDENT 1907-1925/WILLIAM NILES VICE PRESIDENT 1907-1925/JAMES G. CANNON TREASURER 1907-1916/FRANK H. BETHELL TREASURER 1916-1925/JAY DOWNER CHIEF ENGINEER/L.G.HOLLERAN DEPUTY CHIEF ENGINEER/H.W. MERKEL LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT/THEODOSIUS STEVENS COUNSEL/LENGTH OF PARKWAY SIXTEEN MILES/AREA TWELVE HUNDRED ACRES/370 OLD BUILDINGS AND FIVE MILES/OF BILLBOARDS REMOVED TWO MILLION/CUBIC YARDS EXCAVATED AND THE SURFACE/RECOVERED WITH TOPSOIL 30,000/TREES AND 140,000 SHRUBS PLANTED/THIRTY SEVEN BRIDGES AND VIADUCTS BUILT/THE RIVER CLEARED OF POLLUTION/AND THE NATURAL BEAUTIES/OF THE VALLEY RESTORED.

The north side of the monument has a plaque noting that the location was the southern terminus of the original Bronx River Parkway.

The footpath parallels Bronx Boulevard, this portion of which was the original Parkway. Ahead lay the ornate Gun Hill Road overpass and, on either side of it, a two-span arch bridge over the Bronx River, whose course at this point is a U shape.

The inscription reads Gun Hill Road 1921.

The Bronx River from just north of Gun Hill Road.

This was not a long or physically taxing walk. It was level except for a few gentle slopes. This walk was an easily accessible respite from the hustle and bustle of the city, along with a lesson in how a park was created. This was a short, interesting, refreshing walk.

The South End of Roosevelt Island (Manhattan)

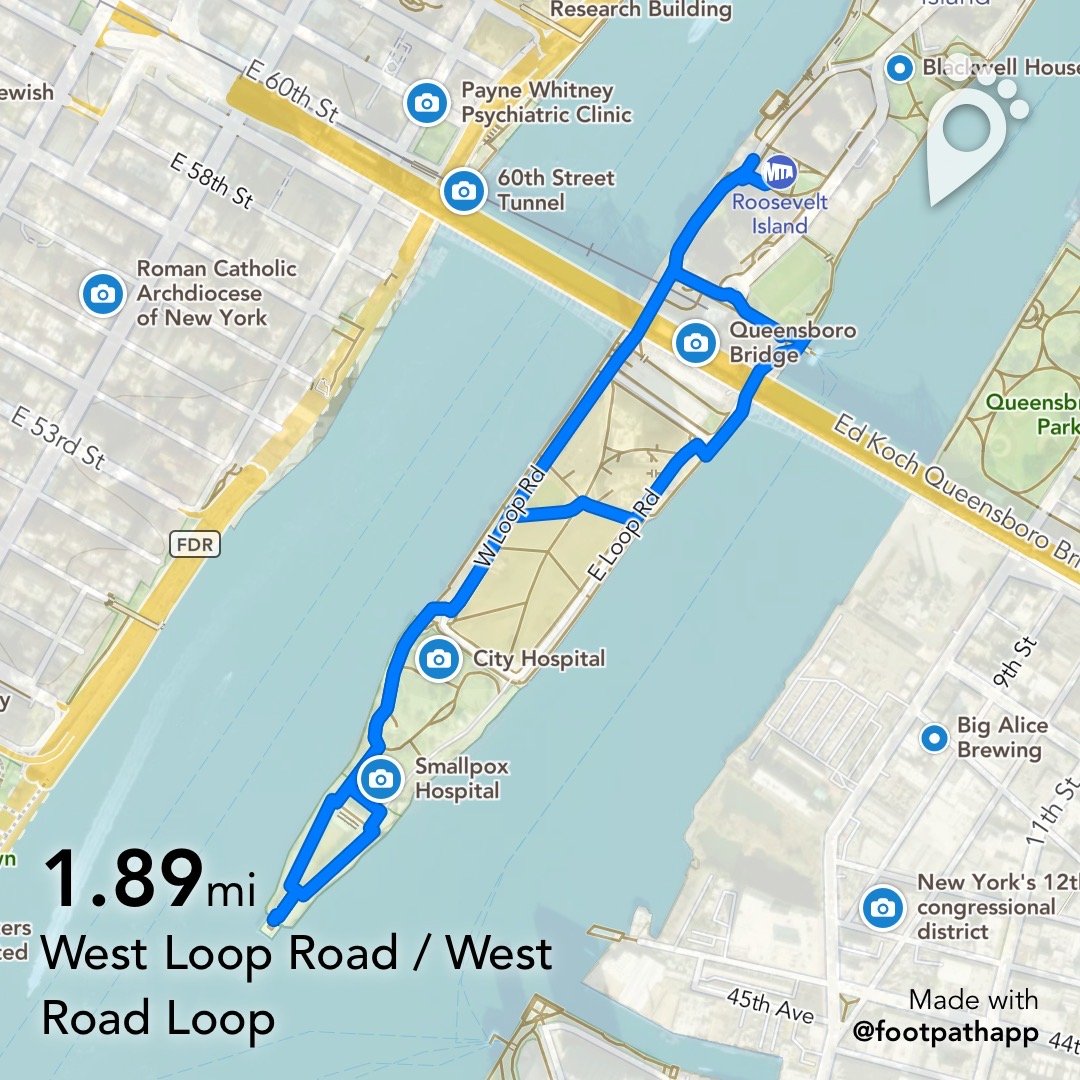

WHERE: The southern third of Roosevelt Island

START/FINISH: Roosevelt Island subway station (F train), fully accessible

DISTANCE: 1.9 miles (3 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl.

Roosevelt Island is a narrow finger of land in the East River. In 1637, Dutch Governor Wouter van Twiller purchased the island, then known as Hog Island, from the Canarsie Indians. After the Dutch surrendered to the English in 1664, Captain John Manning acquired the island in 1666, which became known as Manning’s Island, and twenty years later, Manning’s son-in-law, Robert Blackwell, became the island’s new owner and namesake. The City of New York bought Blackwell’s Island from the Blackwell family in 1828 and over the years constructed the Smallpox Hospital, the Lunatic Asylum, a jail, a workhouse, and other facilities. In 1921 the City renamed the island Welfare Island, and between 1939 and 1952 two new municipal hospitals for the chronically ill, Bird S. Coler Hospital and Goldwater Memorial Hospital, were built. The Fire Department constructed a training facility on the island. When the Queensboro Bridge opened in 1909, an elevator was built to carry pedestrians and vehicles between the bridge and the island. Road access came in 1955 with the construction of the Welfare Island Bridge to Queens.

In 1969 the city leased the island to the New York State Urban Development Corporation for 99 years. The UDC built a new town on the island, which was renamed Roosevelt Island in 1973. In 1976 the Roosevelt Island Tramway opened just north of the Queensboro Bridge, as a temporary measure to take people between Manhattan and the island. Nearly 50 years later, the aerial tramway is a beloved fixture in the cityscape. The subway came to Roosevelt Island in 1989.

From newyorkalmanack.com:

The island was a pioneer in creating barrier free environments with curb cuts, elevators, wide doors, and low counters, according to Judith Berdy, president of the Roosevelt Island Historical Society, which has extensively documented this history, and has a rich archive on the hospital, its leading doctors and some of its patients. She says that the hospital and associated research institutes have hosted many outstanding research scientists and doctors, including hospital director Dr. David Seegal who made advances in nephritis and rheumatic fever, and Julius Axlerod who won a Nobel Prize in Medicine for neuro-pharmalogical research relating to pain relief. Important studies of tuberculosis, arthritis and cirrhosis were also conducted there.

This short walk was around the southern third of the island, south of the Queensboro Bridge. Starting at the subway station, I walked south to the tramway terminal. Here, one of five kiosks that used to serve passengers for the Queensboro Bridge streetcars has been made into a pleasant little visitors center.

From here I crossed over to the Queens side of the island - a very short walk - and walked south past the bridge to the Cornell Tech campus. This research institution is a joint project of Cornell University and the Technion in Haifa, Israel. It opened in 2017 on the site formerly occupied by Goldwater Memorial Hospital.

From newyorkalmanack.com:

The Goldwater Hospital was a monument to the golden years of public health in New York City, designed in distinctive chevrons to offer light and air to all its patients. The rooms had terraces to allow patients direct access to fresh air, and each ward featured a solarium. The hospital had 2,700 windows.

In its early years Goldwater cared for polio patients and ran a wheelchair repair shop with a national reputation for innovation and patient service. Mike Acevedo, nicknamed Dr. Wheelchair, ran it as a “wheel chair pit-stop that maintained and repaired a stock of more than 2,000 wheelchairs.” In his early work during the Vietnam era, they would scavenge parts from model airplanes to use as controls.

There was a nursing school and residence on the island. The Central Nurses Residence had 600 rooms, built by the Works Progress Administration. New York City ran the School of Practical Nursing from 194 -to 1970. One of the most famous nurses is best known outside of her work with patients. Jazz singer Alberta Hunter worked at Goldwater for 20 years, but is most known for her blues recordings of the teens to 1940s. Concealing her age, she studied for a nursing degree, and upon retirement started singing again until she died at age 89.

When Goldwater closed, its patients, many confined to wheelchairs, were moved to Coler Hospital (now Coler-Goldwater Hospital) at the north end of Roosevelt Island, or to the renovated old North General Hospital in Harlem (now the Henry J. Carter Specialty Hospital and Nursing Facility).

The Cornell Tech campus is architecturally excellent; it is light, accessible, and with plenty of space for the general public to walk around. Time will tell what innovations come from there.

Cornell Tech campus.

Crossing the campus, I was back on the Manhattan side of the island, walking south toward the Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park. A short distance past the park entrance was something I didn’t know about before: the FDR Hope Memorial. Completed in 2020, it is a monument to the thirty-second President of the United States overcoming disability. Markers in the pathway commemorate events in his life and afterwards, culminating in something that remains an aspiration.

At the end of the walkway is a bronze statue of FDR in a wheelchair, greeting a girl who has a crutch and a leg brace. I sat on a bench there for a good while, contemplating that Franklin Roosevelt, a son of privilege, rose to greatness only after succumbing to polio in 1921. I thought of my own journey. I might never achieve greatness - I’m not sure I could define “greatness” - but my experience of stroke has given me new purpose. That might be enough. It’s not what I do about the stroke, it’s what I do with the stroke, and I mean to do plenty.

The FDR Hope Memorial is on part of the site occupied by Charity Hospital, previously City Hospital. This was designed by James Renwick and opened in 1861. In 1877, Charity Hospital opened a school of nursing, the fourth such training institution in the United States. The program of education for nurses encompassed two to three years of training in the care of patients and general hospital cleanliness. At Charity Hospital, nurses treated patients, assisted surgeons, weighed and cared for newborns, and took cooking classes. In 1957, Charity Hospital and the neighboring Smallpox Hospital were closed and their patients transferred to Elmhurst Hospital in Queens. Charity Hospital fell into disrepair and was demolished in 1994.

From the FDR Hope Memorial I went past the ruins of the Smallpox Hospital on my way to the Four Freedoms Memorial. The central portion of the hospital, designed by James Renwick, opened in 1856. The north and south wings opened early in the 20th Century. Although a smallpox vaccine existed when the hospital opened, smallpox remained a public health problem in New York City and smallpox patients were kept on Blackwell’s Island, away from the city.

Ruins of the Smallpox Hospital.

The Four Freedoms Memorial was one of the last works designed by Louis Kahn (1902 - 1974), who had the plans with him when he died in New York’s Pennsylvania Station. Kahn was known for outwardly hard-edged buildings; for example, the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, Connecticut certainly is that, but inside it is an outstanding place to view art. Approaching from the north, the visitor passes between a double row of trees that narrow as they approach the point, framing views of the New York skyline and the harbor. The memorial is a procession of elegant open-air spaces, culminating in a 3,600-square-foot (330 square meters) plaza surrounded by 28 blocks of North Carolina granite, each weighing 36 tons. The courtyard contains a bust of Roosevelt, sculpted in 1933 by Jo Davidson. At the north end of the open-air room at the tip of the island is an excerpt from FDR’s Four Freedoms speech of January 6, 1941. Looking at this, I couldn’t help thinking that we surely are led by lesser lights today.

View south from the Four Freedoms Memorial.

There is nothing bombastic about this space; it is cool, contemplative, peaceful. At the far southern end the narrowing entry to the Memorial gives way to the great sweep of the city, looking down the East River.

The walk back to the subway more or less retraced my steps. The southern part of Roosevelt Island is by far more interesting than the northern part. The island as a whole packs in a respectable amount of history.

Ward's Island and Randall's Island (Manhattan and the Bronx)

WHERE: Ward’s Island and Randall’s Island in the East River

START: 96 Street subway station (Q train), fully accessible

FINISH: Brook Avenue subway station (6 train)

DISTANCE: 3.4 miles (5.5 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl except as noted. Map courtesy footpathmap.com

Route of this walk, reading from left to right.

The impetus for this walk was the walk I did two weeks ago, part of which was on the northern part of Randall’s Island. Randall’s Island, Sunken Meadow Island, and Ward’s Island, once separated, were joined together by landfill after World War II, and the combined island is often referred to as Randall’s Island.

The creation of the parks on Ward’s Island and Randall’s Island can be credited to New York’s master builder, Robert Moses, together with Randall’s Island becoming the hub of the Triborough Bridge system. Moses’ mixed legacy is surely evident here: a robust highway network, a fine system of parks, and minimal public transportation (just the M35 bus from Manhattan).

The walk started at the subway station at 96 Street and 2 Avenue, just a short walk from the the promenade on the FDR Drive. The walk from East 96 Street to East 103 Street, where I ascended the ramp to the Ward’s Island Pedestrian Bridge, offered a beautiful view and one surprise: the Vito Marcantonio Peace Garden on the opposite side of the FDR Drive, part of Public School/Middle School 50. According to the United Federation of Teachers website, “the school’s peace garden, which consists of a dual-level atrium, with soil beds on the lower level and a hydroponic garden on the upper level. An outdoor, street-level garden near the elementary-grade classrooms has been a source of pride.” Vito Marcantonio (1902 - 1954) was an Italian-American lawyer and politician, manager of Fiorello La Guardia’s mayoral campaigns, and member of the U. S. House of Representatives. Marcantonio's district was centered in his native East Harlem, New York City, which had many residents and immigrants of Italian and Puerto Rican origin. Fluent in Spanish as well as Italian, he was considered an ally of the Puerto Rican and Italian-American communities, and an advocate for the rights of the workers, immigrants, and the poor. In addition to defending the Puerto Rican and Italian communities and common workers, Marcantonio was a strong advocate of Harlem's African-American communities and fought vehemently for black civil rights decades before the civil rights movement of the 1950s – 1960s.

P.S./M.S. 50, with the Vito Marcantonio Peace Garden.

View from the promenade near East 96 Street: left to right, the Ward’s Island Pedestrian Bridge, Ward’s Island, Hell Gate Bridge, the Queens span of the Robert F. Kennedy (Triborough) Bridge.

At East 103 Street there is a ramp up to the pedestrian bridge from Manhattan to Ward’s Island. Designed by the great Swiss-American bridge engineer Othmar Ammann (1879 - 1965), this bridge opened in 1951. In the New York area alone Ammann also designed the George Washington Bridge, Bayonne Bridge, Triborough Bridge, and Throgs Neck Bridge. This is a vertical lift bridge but the center lift span opens only rarely. On this beautiful Spring day the bridge was busy with walkers, runners, and cyclists going to or from Ward’s Island. The slopes on the ramp and the bridge are steeper than those allowed by the Americans with Disabilities Act and they are not really for people in wheelchairs, but there are handrails the whole way.

Ward’s Island Pedestrian Bridge, looking toward Ward’s Island.

The island has an excellent system of pedestrian and bicycle paths. My friend Ryan and I walked up the west side of Ward’s Island, past the Manhattan Psychiatric Center (behind a high fence) and toward the Little Hell Gate Salt Marsh. Manhattan Psychiatric Center is operated by the New York State Department of Mental Health. This colossal structure, which opened in 1954, continued the New York tradition of putting jails, hospitals for psychiatric patients, and hospitals for people with chronic and long-term illnesses on islands, whether natural (Rikers Island, Roosevelt Island, North Brother Island) or man-made (Hoffman and Swinburne Islands off Staten Island), or elsewhere far from the city.

Manhattan Psychiatric Center. Photo courtesy Creative Commons.

Footpath, west side of Ward’s Island.

Interpretive sign at the Little Hell Gate Salt Marsh.

Little Hell Gate was the body of water separating Ward’s Island from Randall’s Island. Most of it was filled in during the 1960s; the remnant is part of the salt marsh. The branch of the East River separating Randall’s Island from Queens is called Hell Gate, the name coming from the treacherous navigation of this body of water, with its rocks and dangerous currents. Little Hell Gate used to be crossed by a three-span arch bridge with a two-lane roadway, just east of the Triborough Bridge viaduct, that was also designed by Othmar Ammann and opened in 1936. The Little Hell Gate Bridge remained in place for many years after that portion of Little Hell Gate had been filled in and I biked on it before it was demolished around 1990. No trace of it remains.

Little Hell Gate Bridge. The Hell Gate Bridge, used by passenger and freight trains, is behind it. Photograph courtesy Library of Congress.

Crossing Little Hell Gate on a low arch bridge, we entered Randall’s Island and walked east and north past Icahn Stadium to the Randall’s Island Connector. Icahn Stadium was built on the site of Downing Stadium, previously called Triborough Stadium and Randall’s Island Stadium before that, which was demolished in 2002. Both stadiums have hosted interscholastic games, Olympic trials, concerts, and, in the 1930s, professional football. Downing Stadium was built together with the Triborough Bridge and Little Hell Gate Bridge. The light towers at the stadium used to be at Ebbets Field, the home stadium of the Brooklyn Dodgers from 1913 until 1957.

Icahn Stadium. Photograph by Jim Henderson.

The Randall’s Island Connector is an excellent pedestrian and bicycle path that runs underneath the Hell Gate Bridge, across a low arch bridge spanning the Bronx Kill, to East 132 Street in the Bronx. Unlike the Bronx leg of the Triborough Bridge, it requires no climbing. At the Bronx end of the Connector the scene is mostly industrial, but we were surprised by a block of East 133 Street with some trees and some row houses. People live there. We continued to lunch in the neighborhood at the fine Milk Burger at Bruckner Boulevard and St. Ann’s Avenue.

Some years ago some real estate hucksters wanted to re-brand this area the Piano District. In the late 19th Century a number of piano manufacturers set up here to cater to middle class households that wanted pianos. The piano manufacturers are all gone but some of the buildings remain. The whole idea was tone-deaf, ignoring the people who live in this area. This idea died a quick and deserved death.

Randall’s Island Connector.

East 133 Street between Willow Avenue and Cypress Avenue, looking east.

This was a partially accessible walk; the ramps to the Ward’s Island Bridge and the bridge itself are steep, and the Brook Avenue subway station is not accessible, but otherwise the walk is accessible. At the end of the walk there was the option to take the Bx33 bus on East 138 Street to the fully accessible 135 Street subway station (2 and 3 trains).

Randall’s Island and Ward’s Island are excellent for walking, biking, sports, and picnicking. Motor vehicles are mostly out of sight and out of the way. Walking along the Ward’s Island path, I had the feeling of being out of the city, in the city.

Three More Walkable Bridges (Manhattan and Bronx)

WHERE: The Third Avenue Bridge and the Manhattan and Bronx legs of the Robert F. Kennedy (Triborough) Bridge

START: 3 Avenue - 138 Street subway station (6 train)

FINISH: Brook Avenue subway station (6 train)

DISTANCE: 3.27 miles (5.26 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl except as noted. Map courtesy footpathmap.org.

Route of this walk, reading from left to right.

On this trip I walked across three more of New York’s walkable bridges, starting and finishing in the Mott Haven section of the Bronx. At the start of the walk is a triangle bounded by Third Avenue, Lincoln Avenue, and East 137 Street, in the middle of which is a monument to the Bronx men who died in the Spanish-American War in 1898.

From there I walked to East 135 Street, where I crossed to the opposite (west) side of Third Avenue, then continued to the Third Avenue Bridge. This is the third Third Avenue Bridge, all on the same site. The first bridge, built in 1898, was replaced in 1955, and that span was replaced in 2004 - 2005.

Third Avenue Bridge.

At the Manhattan end of the bridge the walk continued on a footbridge over the exit ramp to the Harlem River Drive. The footpath itself curves around a playground to the Harlem River Drive.

Footbridge at the Manhattan end of the Third Avenue Bridge.

Mural at P.S. 30, East 128 Street and Lexington Avenue.

From there I walked east on East 128 Street to 3 Avenue. There is a three-way footbridge to take pedestrians over another exit ramp from the bridge and over East 128 Street. Both footbridges date from the 1955 incarnation of the bridge. While I’m glad there was some thought given to keeping pedestrians safe from motor traffic, it certainly is obvious that accommodating motor traffic was, and in many ways still is, paramount. Neither stairway is wheelchair-accessible. The park and the “Crack is Wack” playground on the north side of East 128 Street are on the site of the 129 Street terminal and repair shop of the Second and Third Avenue elevated railways, demolished after the discontinuance of the Third Avenue el in Manhattan in 1955.

Three-way footbridge at 3 Avenue and East 128 Street.

129 Street terminal, from the corner of 3 Avenue and East 128 Street, 1941. From the collection of Herbert P. Maruska by way of nycsubway.org.

At the corner of 3 Avenue and East 127 Street is the United Moravian Church, which was advertising an upcoming revival.

United Moravian Church

The footpath on the Triborough Bridge is on the south side and access is from 2 Avenue and East 124 Street. On a fence near the entrance is a sad little memorial to a young man who must have been killed there, probably by traffic.

The Triborough Bridge was the brainchild of Robert Moses (1888 - 1981), whose legacy is parks, highways, and public housing projects that are to be found all over New York City and Long Island. The definitive history of Robert Moses and his legacy is The Power Broker by Robert Caro. I cannot recommend this highly enough to students of urban planning, students of politics, anyone. Moses illustrates the truth that we all walk this earth leaving a mixed legacy. The Triborough Bridge, completed in 1936, links the Bronx, Manhattan, and Queens as a hub-and-spoke system with its hub on Randall’s Island. In time, the route from Queens to the Bronx would become part of Interstate 278, and the Manhattan leg would connect with the Franklin D. Roosevelt Drive and Harlem River Drive. I have biked across all three legs of the bridge in the past, and wrote about walking the Queens leg in 2021 in the post “From Queens to the Bronx” on this page, but until this walk had never traversed the other two legs on foot.

The Manhattan leg is a vertical lift span whose towers’ steel structure is vaguely reminiscent of the towers of the George Washington Bridge,

Manhattan leg of the Triborough Bridge, 1936. Photograph by Berenice Abbott.

The Manhattan span has a well-maintained foot and bicycle path on the south side, with a gentle grade walking from Manhattan but a fairly steep ramp down to Randall’s Island.

Foot and bicycle path on the Manhattan leg of the Triborough Bridge.

Looking south from the Manhattan leg of the Triborough Bridge. The arch bridge in the background is the Hell Gate Bridge, used by passenger and freight trains. The suspension bridge to its right is the Queens leg of the Triborough Bridge.

Seen on the ramp to Randall’s Island.

From the bottom of the ramp, turn right, but at the next sign, pointing the way to Queens and the Bronx, do not turn right but go straight ahead, staying on the road and being watchful for the occasional car. Move over to the foot and bike path on the left when it appears.

Randall’s Island and Ward’s Island to the south used to be separated by water, but that body of water, known as Little Hell Gate, has been filled in. The combined island is home to numerous athletic fields and other athletic facilities, picnicking areas, a salt marsh, offices of the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, Fire Department facilities, a psychiatric hospital, and more. The parks are maintained by the Randall’s Island Park Alliance, a public-private partnership. Native Americans called Ward’s Island Tenkenas which translated to "Wild Lands" or "uninhabited place", whereas Randall’s Island was called Minnehanonck. The islands were acquired by Wouter Van Twiller, Director General of the Dutch colony of New Netherland, in July 1637. The island's first European names were Great Barent Island (Ward’s) and Little Barent Island (Randall’s) after a Danish cowherd named Barent Jansen Blom. Both islands' names changed several times. At times Randalls was known as "Buchanan's Island" and "Great Barn Island", both of which were likely corruptions of Great Barent Island. Both islands acquired their present names from their new owners after the American Revolution.

The walk continued on the Bronx Shore Path past baseball fields to the Bronx leg of the bridge. Until the Randall’s Island Connector (described in the post “From Queens to the Bronx” on this page) opened in 2015, the only direct bike and pedestrian route from Randall’s Island to the Bronx was on the Triborough Bridge. The ramp up to the bridge is somewhat steep and has four 90-degree turns, but the walkway is clean and well-maintained, and other people were using it despite the ground-level Randall’s Island Connector being nearby. Going up the ramp, at the “T” intersection go left. A switchback ramp down to the Bronx has an easy slope. It was built in the 1980s to replace stairs.

At the bottom of the ramp up to the Bronx leg of the Triborough Bridge.

On the Bronx leg of the Triborough Bridge, near the top of the ramp from Randall’s Island.

A lot of this part of the Bronx shoreline between the Major Deegan Expressway (Interstate 87) and the waterway called the Bronx Kill is industrial, including a freight rail yard, a Department of Sanitation garage, and a large facility of the New York home-delivery grocer Fresh Direct. Here and there are surprises, like the South Bronx Charter School for International Culture and the Arts, and where I had lunch on this trip, Milk Burger, at the corner of Bruckner Boulevard and St Ann’s Avenue. Not only was the hamburger well worth gong back for, which I will do sooner than later, but I struck up a good conversation with the owner, Erik Mayor, who besides offering a hamburger well worth the trip back to the Bronx has done a lot of good work in this very underprivileged part of the city.

South Bronx Charter School for International Culture and the Arts.

From lunch I walked north on St. Ann’s Avenue and west on this area’s main commercial street, East 138 Street, to the subway at Brook Avenue.

This walk included panoramas of a changing city and closeups that at once echo and defy the panoramas. Not far from the “perfumed stockade” of the Upper East Side of Manhattan, as the late writer Theodore White described it, and not far from the glassy new residential buildings in Mott Haven, a large, poor, proud community gets on with life. This was an easy walk but not one that was wholly wheelchair-accessible. The subway stations where the walk started and finished are not accessible and I had to walk down the ramp to Randall’s Island with care, owing to its steepness.

I think about this walk glad that there are some accommodations for pedestrians and bicyclists but not glad that we are an afterthought in the primacy of motor vehicles. This was part of the mixed legacy of Robert Moses. Thinking about that three-way footbridge on East 128 Street, why can’t pedestrians and bicyclists have a safe ground-level approach to and from the Third Avenue Bridge? These people didn’t matter much to planners like Robert Moses (he was by no means alone). Over the years some improvements have been made to pedestrian and bicycle accommodations at the Triborough Bridge but more are needed, here and throughout the city.

On the Waterfront (Hoboken and Jersey City)

WHERE: The promenade on the Hudson River from Hoboken to Jersey City, New Jersey.

START: Hoboken Terminal (PATH train, fully accessible; Hudson-Bergen Light Rail (fully accessible); Ferries to Manhattan (fully accessible); New Jersey Transit commuter rail (wheelchair lifts on the platforms, otherwise not accessible)

FINISH: Exchange Place station (PATH train, fully accessible)

DISTANCE: 2.3 miles (3.7 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl except where noted. Map courtesy footpathmap.org.

Note: The accessible PATH stations in Manhattan are at 33 Street and World Trade Center. The 33 Street station is accessible from the street and from the 34 Street - Herald Square subway stations (B, D, F, M trains and N, Q, R, W trains, both stations being fully accessible), the latter by way of a passageway with a ramp whose slope exceeds the guidelines of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). This ramp also has no handrails. The way between the subway and the World Trade Center PATH station is accessible but the elevator between the PATH mezzanine and the “Oculus” (concourse) is hard to find. It is on the north side of the fare control area, by the Duane Reade/Walgreens store.

Route of this walk, reading from top to bottom.

This walk illustrates the de-industrialization of the waterfront in Manhattan, Brooklyn, and New Jersey, and the transformation of the waterfront into a valued public space. Since the advent of containerized cargo after World War II, most maritime trade in the Port of New York and New Jersey is handled on the New Jersey side of the river. The waterfront in Hoboken and Jersey City used to be dominated by rail and marine transportation. Several steamship lines had their docks in Hoboken, not Manhattan. The great 1954 film On the Waterfront was filmed in Hoboken. Several railroads had their passenger and freight terminals along this waterfront: the New York and West Shore (later part of the New York Central system) just north in Weehawken; the Delaware, Lackawanna, and Western in Hoboken; and the Erie, the Pennsylvania, and the Jersey Central in Jersey City. All the railroads ran passenger ferries directly from their New Jersey terminals to Manhattan and put freight cars onto barges to be transported across the Hudson River to Manhattan and across New York Harbor to Brooklyn. Only the Pennsylvania would build a direct connection for passenger trains to Manhattan, in 1910, with the tunnels to Pennsylvania Station now used by Amtrak and New Jersey Transit.

Some rail freight traffic is still moved across New York Harbor by barge. Hoboken Terminal is the only one of the riverfront terminals that still exists in active use. The Jersey Central terminal, now the centerpiece of Liberty State Park, hasn’t seen a train since the 1960s.

The Port Authority Trans-Hudson Corporation (PATH) began life in 1908 as the Hudson and Manhattan Railroad (the “Hudson Tubes”), a subway-style service going from 33 Street and Hudson Terminal (near today’s World Trade Center) in Manhattan to Hoboken, Jersey City, and eventually Newark. It connected with the riverfront terminals of the Lackawanna (Hoboken station), the Erie (today’s Newport station), and the Pennsylvania (Exchange Place station), providing a more reliable connection than the railroads’ ferries. The Port of New York Authority, now the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, took over the Hudson and Manhattan in 1962 and operates it today.

The star attraction of this walk is the Manhattan skyline across the river, but the promenade is pleasant and new. Only a block or two inland from the riverfront and the new buildings along it lie an older Hoboken and Jersey City.

Looking south from near Hoboken Terminal.

Looking toward Manhattan from Newport.

We start at Hoboken Terminal, a big, magnificent train station that opened in 1907 and is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Hoboken Terminal from the Hudson River, 2012. The five ferry slips are in front. Photo credit: By Upstateherd - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=62597969

Stop inside the Waiting Room before starting the trip and admire the architecture. Hoboken Terminal is a major multi-modal transit facility, hosting commuter rail, light rail, PATH, local buses, and ferries. New Jersey Transit operates the commuter trains along the former Erie and Lackawanna lines from Hoboken (the Erie moved its trains from its own terminal to the Lackawanna’s Hoboken Terminal in 1956).

Two views of the Waiting Room at Hoboken Terminal.

Exit left from the Waiting Room and follow signs to Light Rail. Stay on the promenade along the river; the light rail station will be in front of you first and then on your left. Continue along the promenade, entering a large area called Newport that was once the site of Erie Terminal. For a detailed history of Erie Terminal and the surrounding area, go to Erie Railroad Terminal - Erie Railroad Terminal - Library Guides at New Jersey City University (libguides.com). Redevelopment of this area began in the 1980s with the construction of the Newport Center shopping mall and accelerated with the opening of the Hudson-Bergen Light Rail in 2000.

The waterfront at Newport.

Erie Terminal, where Newport is now, in the early 1950s. From “Charlie” on flickr.com,

Continuing south along the promenade, we go past a buff-colored brick structure on the right, and its look-alike at the end of a pier on the left. These are two of the four ventilation towers for the Holland Tunnel. The promenade turns to the west at Harsimus Cove, one of the places on this waterfront where rail freight barges once docked. Tall office buildings and hotels dominate the waterfront as one approaches Exchange Place, where the Pennsylvania Railroad once had one of the busiest railroad stations in the world. For a detailed history of the Exchange Place terminal go to Exchange Place - Exchange Place - Library Guides at New Jersey City University (libguides.com). Patronage declined after the Pennsylvania Railroad reached Manhattan in 1910. The terminal and the connecting elevated structure were demolished in the early 1960s. Just to the south of the terminal, the Colgate-Palmolive Company had a factory where the Goldman Sachs tower, which opened in 2004, stands today. The “Colgate Clock” remains, visible from lower Manhattan and a short walk south of Exchange Place on the riverfront.

Pennsylvania Railroad terminal, Jersey City (Exchange Place), circa 1910. Source unknown.

The Colgate Clock; the Goldman Sachs tower is to the right. Photograph by Allen Beatty.

This is an easy walk to enjoy on a nice day. It is full of the history of the waterfront and urban redevelopment. There are plenty of places to stop, relax, have a cup of coffee or a meal, and enjoy the view.

Two More Harlem River Bridges (Manhattan and the Bronx)

WHERE: The Madison Avenue Bridge and Willis Avenue Bridge between Manhattan and the Bronx.

START: 135 Street subway station (2 and 3 trains), fully accessible

FINISH: East 125 Street and 2 Avenue, Manhattan, with these buses to fully accessible subway stations:

M15 to 96 Street (Q train)

M60 SBS to Astoria Boulevard (N and W trains)

M125 to 3 Avenue - 149 Street (2 and 5 trains)

M60 SBS and M125 to 125 Street (4, 5, 6 trains and Metro North Railroad)

M60 SBS and M125 to 125 Street (A, B, C, D trains)

DISTANCE: 2.2 miles (3.5 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl except as noted. Map courtesy footpathmap.com.

Route of this walk, reading from left to right.

Continuing my occasional walks across the walkable bridges of New York City, today I tackled two short bridges across the Harlem River that I have biked across before but had never walked across. This walk started at the subway station at West 135 Street and Lenox Avenue, across from the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, a research unit of the New York Public Library. For more about the Schomburg Center see the post on this page entitled “Harlem and Heights History Walk.” Walking past Public School 197, I noticed this mural.

Crossing 5 Avenue and turning left, I passed the Riverton Houses. These apartment towers were built by the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company in the 1940s, at the same time as Metropolitan Life’s Stuyvesant Town in Manhattan and Parkchester in the Bronx. When they were built the latter two were restricted to white residents, while Riverton was for African-Americans. An apartment in Riverton was considered a step or two up for the people who moved in. Metropolitan Life no longer owns these apartment complexes and they are no longer racially restricted.

Riverton Houses, seen from 5 Avenue.

From 5 Avenue I turned onto the ramp to the Madison Avenue Bridge at East 138 Street. This is a swing bridge that opened in 1910, replacing a smaller bridge that opened in 1882. The slope up to the main span is gentle and the walkway is in excellent condition all the way across.

From the Bronx end of the bridge, for a few blocks to Grand Concourse, one needs to walk with care because of all the cross streets and a lot of turning traffic.

At Park Avenue the Metro North Railroad tracks cross overhead. At this location, on the south side of East 138 Street, there used to be a grand station built by the New York Central Railroad in 1886. The station was closed and demolished in 1973. Nothing remains except a pair of manhole covers.

138 Street station. Image courtesy flickr.com.

Manhole cover at East 138 Street and Park Avenue. NYC&HRRR stands for New York Central and Hudson River Railroad (the name of the New York Central prior to 1914).

I turned north onto Third Avenue, then east onto East 140 Street. (Third Avenue is the only “numbered” Avenue in the Bronx, and is rendered as 3 Avenue only in the subway.). At the corner of East 140 Street and Alexander Avenue is the Mott Haven branch of the New York Public Library, which opened in 1905. A stately center of learning in a low-income neighborhood.

Mott Haven branch, New York Public Library.

Around the corner, on Alexander Avenue, are row houses from the 1890s that would not be out of place in “Brownstone Brooklyn.”

The intersection of East 138 Street and Alexander Avenue is dominated by the 40th Precinct station house of the New York Police Department and St. Jerome Roman Catholic Church.

St. Jerome Church.

The plaque on this statue of Saint Jerome reads “Love without truth is just sentimental. Truth without love is sterile.”

Plaque at the 40th Precinct station house.

This part of the Bronx is known as Mott Haven, named for Jordan L. Mott, who built an iron works on the Harlem River in 1828. The part of the Grand Concourse south of Franz Sigel Park was once known as Mott Avenue. The 138 Street - Grand Concourse subway station was called Mott Haven when it opened in 1918, and in a recent station renovation that got everything right except that it was not made fully accessible, some of the original Mott Haven station mosaics were restored, while other, aesthetically similar mosaics read “138 Street” and “138 Street Mott Haven.”

Mott Haven is a low-income area, part of what has been the poorest Congressional district in the United States, that used to have a lot of light industry, from Mott’s iron works to piano factories (their heyday was in the decades preceding World War I). Near the Harlem River there is still industry but also truck and bus garages and rail lines. After World War II, and after the Third Avenue Elevated was discontinued south of 149 Street in 1955, huge public housing projects were built in the southern Bronx. Through a lot of dislocation, crime, drugs, substandard housing, and much else, people have gone about their lives in an old, largely neglected neighborhood. Recently, new high-rise apartment towers have risen near the Harlem River, and shops and restaurants cater to the new arrivals. I will leave it for people who live in the southern Bronx, including Mott Haven, to say whether this change is good, but it is here. A sleek-looking wine and spirits shop on East 138 Street looked incongruous only at first.

I walked east on East 138 Street past St. Jerome Church and another public housing project, then south onto Willis Avenue. Between East 133 Street (now Bruckner Boulevard) and East 143 Street, the Third Avenue Elevated ran in a private right-of-way, a “clothesline alley,” between Alexander and Willis Avenues. There is no trace of that and most of those blocks have been obliterated by housing projects. Approaching East 135 Street on Willis Avenue there is broken sidewalk by a public housing building, so walk with care. Crossing the Major Deegan Expressway (Interstate 87), I came to the Willis Avenue Bridge. This is an early 2000s replacement of the 1901 Willis Avenue Bridge. The bike and pedestrian path is excellent.

Harlem River rail yard, circa 1920. Collection of Frank Pfuhler via nycsubway.org.

Remnant of the Harlem River rail yard, taken from the same vantage point as the preceding image.

When the city reconstructed this bridge it placed interpretive posters along the walkway. Though marred by graffiti, they still offer valuable history of the area. Beneath the Bronx end of the bridge used to be a freight yard of the New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railroad, and the Harlem River passenger terminal of the New Haven’s subsidiary New York, Westchester, and Boston Railway. I have written about the “Westchester” in the “East Bronx Ramble” post on “The Stair Streets of New York City” page. The Second Avenue and Third Avenue Elevateds cut across and above the freight yards from the Harlem River bridge (between the Willis Avenue Bridge and the Third Avenue Bridge) to “clothesline alley.”

The walk ended at East 125 Street and 2 Avenue, not a subway stop but where there are bus connections to many subway lines. This walk encompassed an area with a lot of change underway. In the last ten years, Mott Haven has seen a lot of change but its many problems remain. I will be back before long to walk across the Third Avenue Bridge.

UPDATE - 13 SEPTEMBER 2023: On WNYC’s “Radio Rookies” series there was an excellent piece on the changes happening in this part of the Bronx, by a young resident of the area. Listen. http://www.wnyc.org/story/christina-adja-gentrification-bronx/

Union Square - Gramercy Zigzag (Manhattan)

WHERE: Union Square north and east to Gramercy Park

START: 14 Street - Union Square subway station (L, N, Q, R, W trains - fully accessible; 4, 5, 6 trains - not accessible)

FINISH: 23 Street subway station (6 train), fully accessible

DISTANCE: 1.67 miles (2.7 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl except as noted. Map courtesy footpathmap.com.

Route of this walk, reading from bottom to top.

One of the delights of walking around New York City is that one can find a lot of interesting things to see just around the corner, or on a short walk. So it is on this walk in the neighborhood of my office.

The walk begins at the top of the elevator and escalator from the concourse of the 14 Street - Union Square subway station complex to East 14 Street. The complex encompasses three stations, two of which are fully accessible. The station that is not accessible, on the Lexington Avenue Line (4, 5, 6 trains) is part of the First Subway that opened in 1904. The layout of this station will make accessibility a major challenge.

The elevator and escalator to the street are part of Zeckendorf Towers, a mixed-use development from the 1980s on the site formerly occupied by the S. Klein department store. Klein’s motto was “On the Square,” an allusion to the Union Square location of its flagship store and a suggestion of fair prices.

Nighttime view, S. Klein department store with the Consolidated Edison building in the background, 1935. Photo courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York via urbanarchive.org.

Walking east on East 14 Street, one passes the site of a longtime and long gone German restaurant, Luchow’s, before coming to Irving Place. From urbanarchive.org:

Luchow’s was a German restaurant/beer garden. It opened in 1882 at 110 East 14th Street at a time when the East Village was known as “Little Germany”, or Kleindeutschland. The restaurant would expand over the years in size and prominence, eventually occupying a space eight times as large as the original venue. In its heyday, Luchow’s was the place to see and be seen if you were a part of the music, theater, or literary crowd. It imported 70,000 half-barrels of beer a year, a daily consumption of 24,000 liters. Famous diners included Theodore Roosevelt, Diamond Jim Brady, Oscar Hammerstein, John Barrymore, Enrico Caruso, Sigmund Romberg, Lillian Russell, O. Henry, Theodore Dreiser, Thomas Wolfe, and Edgar Lee Masters. Luchow’s was the first restaurant in the city to get its liquor license following Prohibition’s repeal in 1933.

Interior of Luchow’s (1902 postcard).

Luchow’s in 1975. Photo courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York via urbanarchive.org.

Just across Irving Place is the headquarters of Consolidated Edison, which provides electric power and natural gas in New York City and Westchester County. The Con Edison building is on the site of the old Academy of Music (1867), a huge concert venue that could not compete with the Metropolitan Opera, which opened its opera house at Broadway and West 39 Street in 1883.

Walk up Irving Place one block, then right (east) on East 15 Street. At the northwest corner is the Irving Plaza music venue. Cross 3 Avenue, then stop at Rutherford Place. On either side of East 15 Street are buildings of the Friends Seminary, a private school founded by the Society of Friends (the Quakers) in 1786.

Two buildings of Friends Seminary, across from each other on East 15 Street.

According to The Street Book by Henry Moscow (Hagstrom Company, 1978), Rutherford Place was named for Colonel John Rutherford, “a member of the committee that laid out Manhattan’s streets and avenues beginning in 1807.” On the east side of this quiet little street is Stuyvesant Square, a park dating from 1836 that is bisected by 2 Avenue and is surrounded by a magnificent wrought iron fence. Along this walk one will see a lot of beautiful wrought iron work. The west side of Rutherford Place is dominated by the Friends Meeting House (1860), St. George’s Episcopal Church (1846 - 1856), and St. George’s Chapel (1911 - 1912).

Looking north on Rutherford Place from East 15 Street.

Rutherford Place entrance to Stuyvesant Square.

Entrance to the Friends Meeting House.

St. George’s Church.

St. George’s Chapel. Above the doorway is a bas-relief of St. George slaying the dragon and the words “Fight the Good Fight of Faith.”

At the end of Rutherford Place, on the north side of East 17 Street, is a striking row of houses (1877 - 1883), the easternmost of which has statuettes of coachmen above the first floor, reminiscent of the old “21 Club” in Midtown.

Turning left (west) on East 17 Street, we pass more late 19th century brownstone and brick buildings, and decorative wrought iron. Crossing 3 Avenue, one sees a relic of the days when this was a German neighborhood and the Third Avenue Elevated thundered overhead: Scheffel Hall (1894), once the German-American Rathskeller (beer hall), later the club Fat Tuesday’s, now in need of a new use and a lot of tender loving care. At the southwest corner of East 17th Street and Irving Place is the onetime home of the American author Washington Irving (1783 - 1859), marked by a plaque.

Wrought iron on East 17 Street.

Washington Irving plaque, southwest corner Irving Place and East 17 Street.

Continuing west on East 17 Street, we come upon the former Tammany Hall, by which name the regular Democratic Party (the “machine”) in Manhattan was long known. Tammany Hall is often associated with William Marcy “Boss” Tweed, its leader and de facto New York mayor, in the 1860s and 1870s, but Tammany Hall long outlasted Tweed. This, the last Tammany clubhouse, opened in 1928 and as of this writing is being converted to commercial use. The downfall of Tammany Hall occurred in the 1960s, led by progressives, one of whom was Edward I. Koch (1924 - 2013), who would go on to become a three-term Mayor.

Tammany Hall.

Turning right onto Park Avenue South, on the right is the W Hotel Union Square, formerly the Guardian Life Insurance Company, formerly the Germania Life Insurance Company (1910 - 1911). Germania changed its name to Guardian in the wake of anti-German sentiment during World War I. Turn right on East 18 Street, then left on Irving Place. At the northeast corner is Pete’s Tavern, in a building dating from 1829. Legend has it that O. Henry wrote “The Gift of the Magi” here. Looking up Irving Place, note Gramercy Park in the near distance, and Midtown towers such as the Chrysler Building in the far distance.

Pete’s Tavern.

Turn left on East 19 Street. On the north side of the street is 81 Irving Place, a building with a lot of bas-reliefs.

South facade of 81 Irving Place.

A bit farther along is 110 East 19 Street, a Beaux-Arts building with metal roll-down shutters. This is an electrical power substation for the subway, built by the Interborough Rapid Transit Company in 1904 for the First Subway. Cross Park Avenue South, and at Broadway turn right. On the opposite corner is the massive Arnold Constable building (1869), long home to the Arnold Constable and Company department store.

IRT (now New York City Transit Authority) electrical substation, 110 East 19 Street.

Arnold Constable building, East 19 Street and Broadway.

Turning right from Broadway onto East 20 Street, we pass on the right the birthplace and childhood home of Theodore Roosevelt (1858 - 1919), the twenty-sixth President of the United States (1901 - 1909). This house is maintained as an historic site and museum by the National Park Service.

Theodore Roosevelt birthplace, 28 East 20 Street.

Cross Park Avenue South and continue toward Gramercy Park. On the south side are two famous private clubs: the National Arts Club (1881 - 1884) and, next door, the Players’ Club (1845, remodeled 1888 - 1889). The Players’ Club was founded by Edwin Booth (the same Booth family as John Wilkes Booth) for people associated with the theatre and so it remains. Years ago I had dinner there as the guest of a theatre person who was a member of the club.

The Players’ Club (left) and the National Arts Club (right)

Wrought-iron extravaganza in front of the Players’ Club.

Gramercy Park is an inspired use of space even though it is a private park. Only people living in the buildings surrounding it, and members of the Players’ Club and National Arts Club, can use a key to enter the park. It was developed by one Samuel Ruggles in 1831, when this area was beginning to be developed. From The WPA Guide to New York City (1939):

The park’s creator, Samuel B. Ruggles, was among the first of New York’s early real-estate operators to offer for sale a development with building restrictions. He caught the fancy of the rich by guaranteeing to a selected group - those who bought his property - the exclusive us of a private park as a permanent privilege. Keys - no longer golden - to the iron gates are distributed to owners and tenants under the close scrutiny of the trustees of Gramercy Park. Residents in near-by streets who have been approved by the trustees are given keys for annual fees. All others must be satisfied with a glimpse through the gate.

Gramercy Park was a marsh in 1831 when Ruggles drained it, laid out the green and the streets on the model of an English square and offered sixty-six lots for sale. The privacy of Gramercy Park was violated only once, when troops encamped within this sacrosanct area during the Draft Riots in 1863.

Gramercy Park, looking north.

Detail of wrought-iron fence surrounding Gramercy Park.

Turn left onto Gramercy Park East, then left again onto East 21 Street, then right onto Lexington Avenue. 34 Gramercy Park East (1883) is an extravagant, wonderful structure. A passer-by told me that no. 34 is the oldest apartment house in the city (it isn’t) and that the television host Jimmy Fallon lives there.

34 Gramercy Park East.

On Lexington Avenue, cross East 23 Street and then turn left (west). The walk ends at the 23 Street subway station, at Park Avenue South. The elevator to uptown trains is on the near corner, while the elevator to downtown trains is across Park Avenue South.

This short walk certainly packed in a lot to savor about the city: a lot of history and a lot of change. It is fully accessible, and the only curb cuts that are at all problematic are when one goes east on East 20 Street crossing Park Avenue South.

Elmhurst, Jackson Heights, and Woodside (Queens)

WHERE: The neighborhoods of Elmhurst, Jackson Heights, and Woodside, in Queens

START: Junction Boulevard subway station (7 train), fully accessible

FINISH: 61 Street - Woodside station (7 train and Long Island Rail Road), fully accessible

DISTANCE: 2.9 miles (4.3 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl. Map courtesy footpathmap.com.

Route of this walk, reading from right to left.

When Pope John Paul II led the Roman Catholic Church, somebody once said that he could have spared himself all his overseas trips and just visit Elmhurst, Queens, with all the nationalities living there. This walk was inspired by the excellent book The Intimate City: Walking New York by the architecture critic of The New York Times, Michael Kimmelman, and took in a fascinatingly diverse and changing area.

In 1898 New York City, which previously had been confined to Manhattan and part of the Bronx, absorbed the rest of modern-day Bronx (then part of Westchester County), Brooklyn, Staten Island, and the western part of Queens County. The eastern townships in Queens County became Nassau County. This area of the new Borough of Queens was part of the pre-1898 Town of Newtown. It had some streetcar lines in the early 20th century but it only became developed after the Queensboro Bridge opened in 1909 and especially after the elevated subway along Roosevelt Avenue opened in 1917. A housing boom soon followed.

This walk started at the Junction Boulevard subway station on the edge of Elmhurst, in the midst of a busy commercial area. Here, the predominant language is Spanish, and people from all over Latin America live here. Along Junction Boulevard and elsewhere on this walk, shopkeepers took advantage of the sunshine to move a lot of their wares outside. At 37 Avenue the walk turned west. 37 Avenue runs parallel to Roosevelt Avenue and both are busy commercial corridors, but 37 Avenue is somewhat more serene as, unlike Roosevelt Avenue, it does not have elevated subway tracks overhead.

Intersection of Junction Boulevard and Roosevelt Avenue, at the subway station.

Junction Boulevard between Roosevelt Avenue and 37 Avenue.

Walking west on 37 Avenue into Jackson Heights, the commerce was busy and just as diverse. The history of Jackson Heights is an interesting study in early 20th century urban development. Before 1900, Jackson Heights did not exist; it was just an unnamed part of Newtown. The name was invented by the Queensboro Corporation, which had acquired the land, constructed utilities and paved roads, and began the construction of apartments surrounding common gardens. The demand for housing in Jackson Heights was great and between 1919 and 1929 new housing was constructed at a rapid pace in both Jackson Heights and Elmhurst. These were cooperative apartments, not rentals, and when built they were restricted to white Anglo-Saxon Protestants. How times have changed.

82 Street between 37 Avenue and the subway station at Roosevelt Avenue is another very busy commercial block. The co-naming Calle de Colombia probably wouldn’t have passed muster decades ago.

On 37 Avenue near 81 Street is Jahn’s, an old-time ice cream parlor and family restaurant. There used to be Jahn’s in the Richmond Hill neighborhood of Queens, on Kingsbridge Road in the Bronx, and elsewhere around the city. Jahn’s is celebrated for the Kitchen Sink sundae, an extravaganza of ice cream and toppings.

From 37 Avenue I turned north on 81 Street and met my old friend Clarence Eckerson, who did the video that appears on the post “The Stick It to the Stroke Stair Climb and Gallivant” post on the page “The Stair Streets of New York City,” and his family. At the corner of 35 Avenue we spotted a street sign honoring the inventor of Scrabble, Alfred Butts, who lived in Jackson Heights and invented the game while living there.

The Scrabble sign at 35 Avenue and 81 Street. Note the lower street sign with the letters showing the letter scores they have in Scrabble. A clever, great tribute.

From 81 Street we turned west onto 34 Avenue, a long stretch of which has been turned into an “open street” for pedestrians, bicycles, and a greenmarket, watching for cars only at the cross streets. Barricades keep cars off 34 Avenue from 7 AM until 8 PM. At 78 Street we passed what in 2008 became a temporary play street that has been made permanent.

This and the following image show how 34 Avenue has becoome a place for people.

The New York City Department of Transportation placed concrete blocks at intersections to demarcate the open street. A local resident gave this one some local color.

We turned south on 74 Street. The block between 34 and 35 Avenues is a mix of attached houses and apartment buildings, typical of the side streets in Jackson Heights. Near Roosevelt Avenue and a major subway station, we passed a block of Indian restaurants, sari shops, and other stores, turning onto Diversity Plaza, a car-free pedestrian space.

74 Street between 34 and 35 Avenues.

Diversity Plaza between 74 and 73 Streets.

From Diversity Plaza we walked west on Roosevelt Avenue underneath the elevated subway, along low-rise 39 Avenue, south on 61 Street to the subway and Long Island Rail Road station at Roosevelt Avenue, and then to Donovan’s Pub at 58 Street and Roosevelt Avenue for their great hamburgers. This area, the end of the walk, is Woodside, once heavily Irish Catholic but now fully as diverse as Jackson Heights. In the early 19th century this area, like much of Newtown, was farmland. Plank roads to the East River and railroads were built and farmland gave way to country estates. The opening of the subway in 1917 led to a building boom here as in Elmhurst and Jackson Heights. The 61 Street - Woodside station is a hub for the subway, several bus lines (including one to La Guardia Airport), and the Long Island Rail Road.

This walk was a feast for the eyes with plenty to enjoy, and restaurants along the way catering to just about every taste. It was a fully accessible walk. There were curb cuts at every intersection and nearly all are in very good condition. On 74 Street I encountered two narrow sections of sidewalk going past trees, but they are wide enough for a wheelchair. For someone wanting an easy excursion through a very diverse area, this walk would be hard to beat. And if you want to cut the walk short, at 74 Street and Roosevelt Avenue turn east one block, enter the subway station at street level at 75 Street, and take the elevator up to the 7 train or down to the E, F, M, or R trains.

Don’t Underestimate the Power of a Walk

This item from the Harvard Business Review isn’t about a specific walk around town but it is about walking. It is worth reading.

Tribeca to Greenwich Village (Manhattan)

WHERE: The lower West Side of Manhattan

START: Chambers Street subway station (1, 2, 3 trains); fully accessible

FINISH: 14 Street - 8 Avenue subway station (A, C, E, L trains); fully accessible

DISTANCE: 2.45 miles (3.9 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl. Map courtesy footpathapp.org.

Route of this walk, reading from bottom to top.

The days immediately following the year-end holidays are a good time to hit the streets of Manhattan without being overwhelmed by traffic. So on the first Saturday of 2023 I chose a walk without hills, stair streets, or walkable bridges, but with plenty to make me stop and look. I chose a walk that started in what was once just the lower West Side but in the 1980s was re-branded “TriBeCa” for Triangle Below Canal Street, that would end with a zigzag through Greenwich Village. The course was flat and, with some qualifications, accessible.

Coming out of the subway at the intersection of Chambers Street, Hudson Street, and West Broadway, I was greeted by a public plaza in what used to be the southernmost block of Hudson Street.

Looking east on Reade Street from Hudson Street. I saw this painted sign that has baffled me for years.

A block north was the evolution of this neighborhood in one visual: a nicely restored nineteenth century building on the corner, the great Western Union building of 1930 (Ralph Walker, architect), and a modern residential tower designed by Frank Gehry in the right background.

A block north is little Duane Park, one of my favorite spots in the city. The loft buildings on the south side of Duane Street used to be home to wholesalers of eggs, milk, and butter. Such clusters of food wholesalers once were found around Manhattan, near the Hudson River or East River. Eventually, these businesses relocated to modern facilities at Hunts Point in the Bronx.

Leading north from Duane Street is two-block long Staple Street, another favorite of mine. From The Street Book by Henry Moscow (Hagstrom Company, 1978):

The Namesake: staple products that were unloaded there. Under Dutch law that was effective in New Netherland, ships in transit had to pay duty on their cargo or offer the cargo for sale. In New Amsterdam, Staple Street was the marketplace for such goods.

Staple Street is beguiling: narrow enough that one can, and should, walk safely in the street and not on the too-narrow sidewalks. At the north end is the onetime home of the New York Mercantile Exchange.

Staple Street, looking north.

Former New York Mercantile Exchange, Harrison Street west of Hudson Street

From Staple Street I turned right onto Harrison Street and left on Hudson Street. At Hudson and North Moore Streets is a popular restaurant called Bubby’s, with a line to get in for brunch.

The Saturday brunch queue at Bubby’s.

This part of Manhattan used to be home to food wholesaling as noted before, plus suppliers to the maritime industry when the Hudson River shoreline was a phalanx of docks from the Battery to 59 Street, and other light industry. That didn’t prevent individual buildings from having artistic flourishes; witness the Mercantile Exchange and the corner of this building at Beach and Hudson Streets.

At this point, on the east side of Hudson Street is the exit plaza for the Holland Tunnel. This plaza was built on the site of St. John’s Park. Continuing north, cross Canal Street, turn left, and then turn right onto Renwick Street. This one-block street has seen a lot of change in recent years, not limited to the new building on the left.

Renwick Street, looking north.

At the end of Renwick Street, turn left onto Spring Street and cross Greenwich Street. Ahead is a fine, favorite old watering hole, the Ear Inn. It is in a building constructed around 1770 and became the home of James Brown, an African aide to George Washington in the Revolutionary War and, later, a successful tobacco merchant. More history of the Ear Inn is at http://www.theearinn.com/about. When it was built the Hudson shoreline was just to the east of where Washington Street is now and just west of the Ear Inn.

Turning around and walking east on Spring Street, past Hudson Street, I came upon the New York City Fire Museum. I had walked past it many times but had never gone inside until this day. It is completely accessible and is well worth a visit. It has a lot of old fire fighting equipment and other paraphernalia, plus an excellent, heartbreaking permanent exhibit of artifacts from the World Trade Center and a tribute to the 343 New York City fire fighters who died in the attack on September 11, 2001.

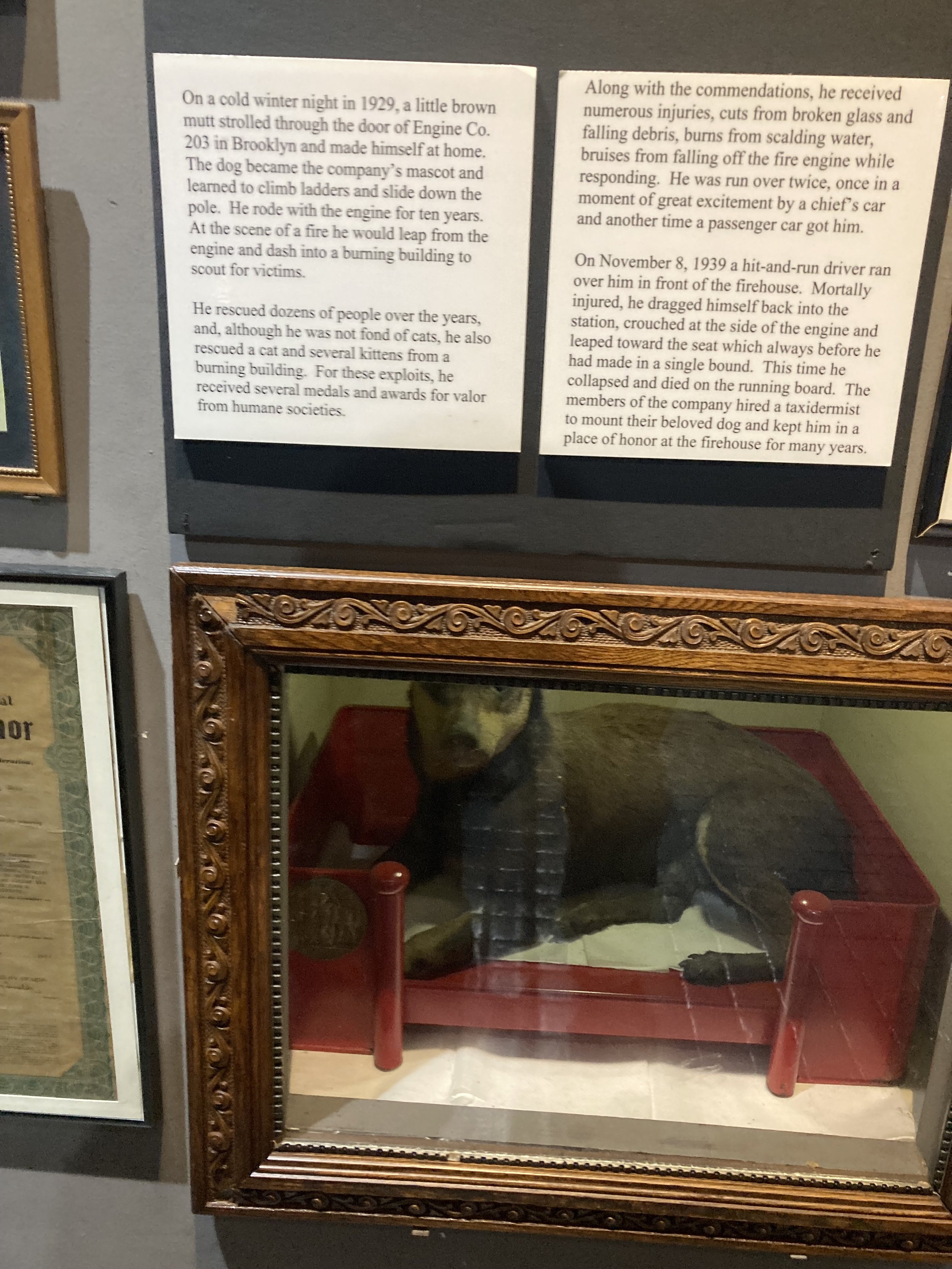

There’s a section of the museum devoted to fire house dogs.

From Spring Street the walk continued left (north) on uninteresting Varick Street. I turned right (east) onto Carmine Street for a block, then turned left (north) onto narrow Bedford Street. Crossing 7 Avenue South and staying on Bedford Street, be on the sidewalk on the right side as the other sidewalk is just too narrow. Turn left onto Commerce Street and see the Cherry Lane Theatre, a celebrated Off-Broadway stage.

Cherry Lane Theatre on Commerce Street.

From Commerce Street I turned right (east) on Barrow Street, then left (north) on Seventh Avenue South. This street didn’t exist prior to the IRT subway being constructed in the 1910s. The large number of empty storefronts and once busy restaurants testify to how hard the pandemic has been on small businesses.

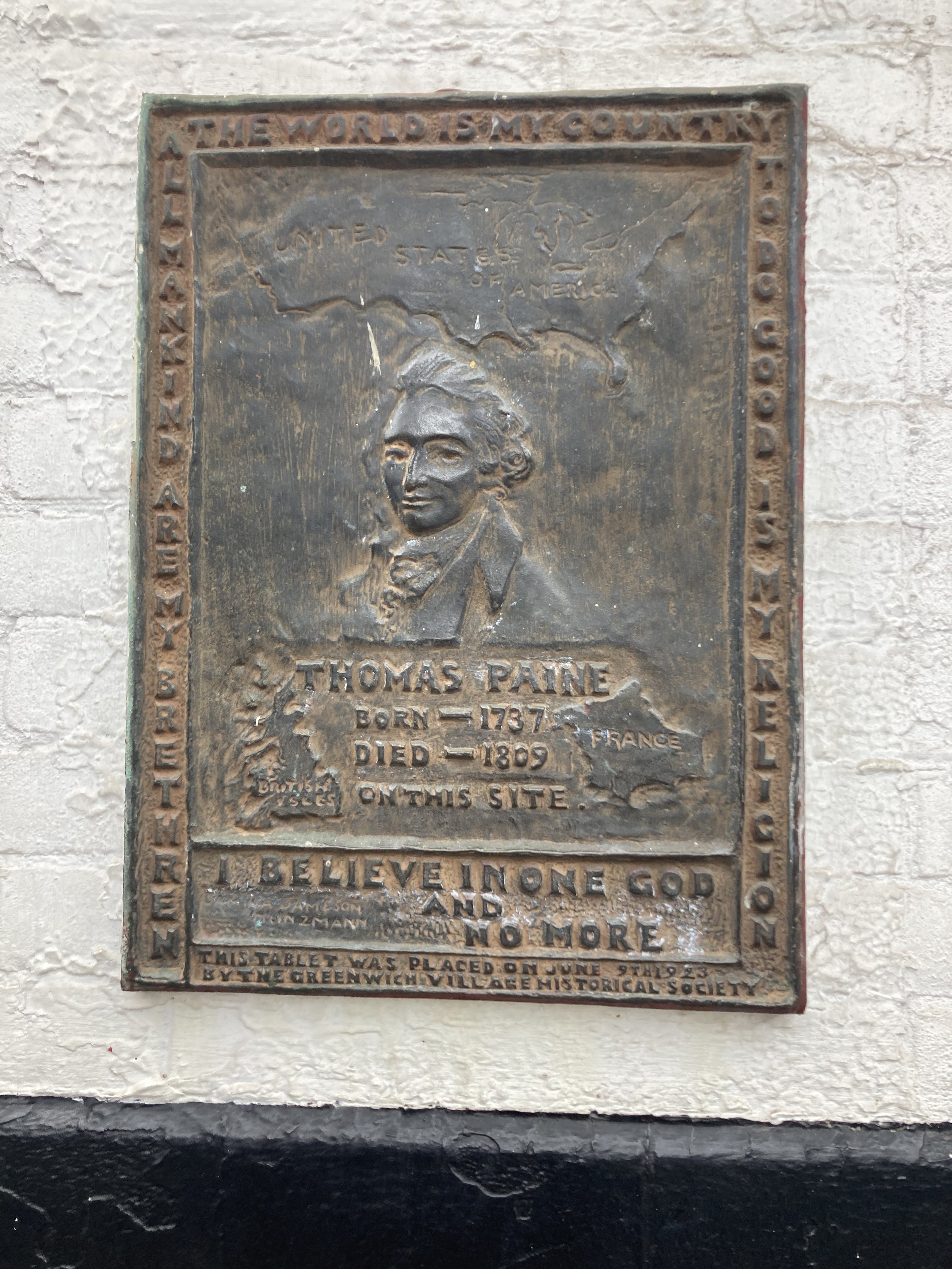

Off to the left are Marie's Crisis Cafe and a jazz and blues venue called Arthur’s Tavern. On the facade of Marie’s Crisis was this example of history hiding in plain sight. Thomas Paine wrote a series of pamphlets during the American Revolution under the banner of “The American Crisis” and this is the Crisis in Marie’s Crisis Cafe, not any crisis suffered by Marie.

A bit to the north, on the east side of 7 Avenue South, is Sheridan Square and the Stonewall National Monument. On Christopher Street, across from the park, is the Stonewall Inn, an important location, but by no means the only one, in the struggle for LGBTQ rights that is far from finished. This is one part of civil rights and it is fitting that there is a memorial in this place.

Just to the north on West 10 Street, is a jazz club called Small’s. At one time, when it was owned by a fascinating, kind character named Mitch Borden, it was a BYOB place where, having paid to get in, one could stay the whole evening and hear excellent jazz by little-known performers. A bit farther north is the famed Village Vanguard, a jazz mecca for generations. It is a triangular space downstairs from the sidewalk, the musicians playing in one apex of the triangle. The bar is on the side of the triangle opposite the stage and it was my preferred place to sit, looking out over the tables and perhaps chatting with the bartender.

I turned north onto Waverly Place and then left (west) on West 11 Street, then right (north) on West 4 Street. An intersection of West 4 and West 11 Streets, one might wonder. Only in New York, I suppose.

Timely sign on West 11 Street.

After lunch at Xi’an Famous Foods at 8 Avenue and West 15 Street (terrific food but the seating seems to have been designed for small children), the walk ended at the subway station at 8 Avenue and West 14 Street. This busy station is home to whimsical bronze sculptures by Tom Otterness, starting at the elevator on the street and continuing throughout the station.

My favorite group of sculptures in the station. Two men are trying to saw away the support column. That great creature of urban myth, the New York sewer alligator, grabs someone for its meal while someone else just looks on. Whimsical and unsettling at the same time.

This was a most enjoyable walk. The southern part of the walk had paving blocks that had to be negotiated with some care. Mere steps from either side of the walk was so much more to see. I wanted to put together a completely accessible walk with a lot to see, and I succeeded. I could have lingered at many places on the walk. You might choose to do so.

Ridgewood, Maspeth, and Two Bridges (Queens and Brooklyn)

WHERE: From Ridgewood, Queens, through Maspeth, Queens, across two bridges to East Williamsburg, Brooklyn

START: Forest Avenue subway station (M train)

FINISH: Grand Street subway station (L train)

DISTANCE: 3.1 miles (5 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl. Map courtesy footpathapp.org.

Route (reading from right to left) and profile (reading from left to right) of this walk.

For this last walk of 2022 I decided to walk across the two Newtown Creek bridges I had not yet crossed on foot (I have biked across both many times), beginning with a walk through the Ridgewood and Maspeth neighborhoods of Queens. The bridges are on Grand Street and Metropolitan Avenue.

The walk started at the elevated Forest Avenue subway station, in a quiet corner of Ridgewood. Ridgewood used to be home to a lot of people of German and Eastern European heritage, augmented in recent years by Hispanic people, people from the Balkans, and people priced out of places such as Williamsburg. A few blocks into the walk I noticed Rosemary’s Playground. From the New York City Parks website:

Rosemary's Playground is named for one of Ridgewood's brightest political leaders, who lived much of her life at 1867 Grove Street. Born in Brooklyn on February 7, 1905, Rosemary R. Gunning (1905-1997) graduated from Richmond Hill High School in Queens in 1922. Soon after she received the L.L.B. from Brooklyn Law School in 1927, she was admitted to the bar in New York State. Rosemary worked for a Manhattan and Long Island law firm during the Great Depression, and then served as an attorney for the Department of the Army from 1942 to 1953. She married Lester Moffett in 1946.

Ms. Gunning entered the New York political scene as a Democrat and later joined the Conservative Party. One year after she attended the 1967 New York Constitutional Convention, Rosemary became the first woman to be elected to the New York State Assembly from Queens. During four two-year terms, her major achievements included bills supporting school decentralization and the creation of the Housing Court.

A bit farther along Fairview Avenue I came upon an old German beer hall that appears to have an outdoor beer garden. I’ll be back. Gottscheer Hall gets its name from the county of Gottschee in present-day Slovenia. An interesting history of Gottschee and the migration of Gottscheers to New York and elsewhere is at https://gottscheerhall.com/history

When I was mapping out this walk I saw that along the way was a little one-block street with the grand name of St. John’s Road. So I had to include it on the walk. If anyone knows how this street got its name, please let me know!

St. John’s Road, looking west from Grove Street.

Holiday display on St. John’s Road.

From there I continued along Woodward Avenue, past Linden Hill Cemetery, founded in 1842. Its hilltop location affords an excellent view of Manhattan in the distance. The evolution of Ridgewood is captured in the diversity of family names on the gravestones. Alas, the wrought iron fence around the cemetery is topped with barbed wire and the entrances to the cemetery are festooned with all sorts of “don’ts.”

Downhill from the cemetery, I turned from Woodward Avenue onto Troutman Street. At the end of Troutman Street, at the intersection of Flushing Avenue and Metropolitan Avenue, is the former warehouse of the H.C. Bohack Company. Bohack was a supermarket chain in Brooklyn, Queens, and Long Island from 1887 to 1977. The first time I saw this, on a bike ride in the area in 2015 (when I took the photo below), I was astonished that this bit of history was extant.

From Troutman Street almost to the end, the walk was ugly. I passed a lot of warehouses, wholesalers of all kinds of things, a big lumber yard, an equally big New York City Transit bus garage, small metalworking firms, and truck terminals. But ugly places like these are vital to the City’s economy. On 54 Street I saw some private houses incongruously placed amid all this, and the former Bushwick Branch of the Long Island Rail Road, which still sees the occasional freight train. It has not seen a passenger train since 1924.

The Maspeth Business Park on Grand Avenue (it becomes Grand Street in Brooklyn, west of the Grand Street Bridge). Look at the signs. All this time I thought Queens met the world at JFK Airport.

Eventually I came to the Grand Street Bridge, a swing span built in 1903. I’ve biked over the bridge and its challenging steel grate roadway many times but had never walked it before. It crosses the most polluted section of one of the most polluted waterways in the United States, Newtown Creek. In the image, note the small wooden shack at mid-span. That was a challenge to shimmy past.

Past the Grand Street Bridge, I passed more of the same until a short detour onto Stewart Avenue to Metropolitan Avenue. Ahead lay the Metropolitan Avenue Bridge, a double-leaf drawbridge that opened in 1933. It crosses the English Kills, a heavily polluted tributary of Newtown Creek. Just east of the bridge was a mural that I couldn’t explain but caught my eye.

Metropolitan Avenue Bridge, looking west.

View of English Kills from the Metropolitan Avenue Bridge.

If you ever walk along the north walkway of the Metropolitan Avenue Bridge (I didn’t), do not attempt to cross the exit to westbound Metropolitan Avenue. There is too much fast-moving traffic.

Continuing along Grand Street, warehouses and light industry dominate the south side of the street, while the north side changes slowly with new restaurants and a film camera business (to which I’ll go back) alongside a long-standing auto repair business. The end of the walk was the Grand Street subway station at the top of a gentle hill. This station is being made accessible, and the elevators and other improvements should be complete in 2023.

Elevator tower under construction to the Manhattan-bound platform of the Grand Street subway station.