Staten Island Ramble #1

WHERE: Just west of the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge, Staten Island

START: Grasmere station, Staten Island Railway

FINISH: Bay Street and Hylan Boulevard, then S51 bus to St. George Ferry Terminal

DISTANCE: 2.4 miles (3.9 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl and Jordan Centeno as noted. Maps courtesy of Google Maps.

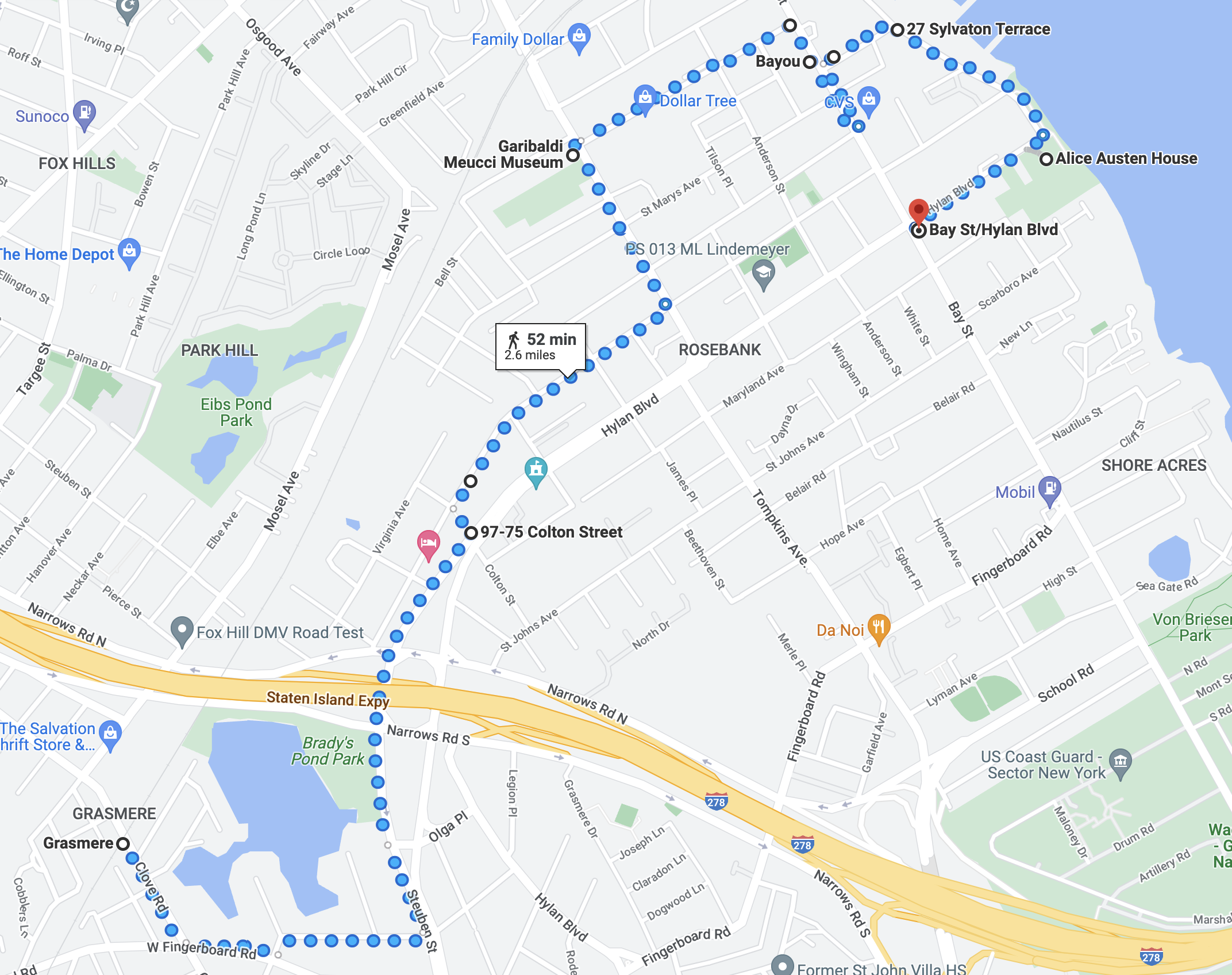

Route of this walk, reading from left to right.

The impetus for this walk was tackling my first stair street on Staten Island, Colton Street in the Rosebank neighborhood. See the post “Colton Street (Staten Island) on The Stair Streets of New York City page. But I was also able to visit two small museums in the area: the Garibaldi-Meucci Museum and the Alice Austen House. My friends Jordan Centeno and Matt Summers joined me on the walk.

We started by taking the Staten Island Railway from the St. George Ferry Terminal to Grasmere station. Grasmere is a quiet suburban neighborhood with sidewalks that are not always wide or even continuous. It reminded me of some of the leafier neighborhoods of eastern Queens.

Grasmere street scene: Windermere Road. Photograph by Michael Cairl.

From Grasmere station it was a more or less steady (but not steep) climb to past the Staten Island Expressway (Interstate 278), then a slight downhill to the Colton Street stairs. We descended the stairs to Clifton Avenue, then through a residential area to the commercial strip of Tompkins Avenue, then to the Garibaldi-Meucci Museum.

Why are there three crucifixes iin the parking lot of St. Joseph’s School? To let wayward whelps know the fate that might befall them if they fell afoul of one of their teachers? Photograph by Michael Cairl.

The Garibaldi-Meucci Museum on Tompkins Avenue. Photograph by Michael Cairl.

Michael and Matt goofing it up at the fence in front of the museum, before realizing the entrance was on Chestnut Avenue. Photograph by Jordan Centeno.

Historical marker outside the Garibaldi-Meucci Museum. Photograph by Michael Cairl.

Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807 - 1882) was a leading figure in the creation of a unified Italy from a collection of kingdoms and the Papal States. Unification was completed in 1870 when the Pope lost control of Rome and its surrounding region of Lazio. As a young adult Garibaldi entered the merchant marine and led rebellions in Brazil and Uruguay before returning to Italy to participate in the revolutions of 1848. He escaped with his life and sailed to New York to buy a merchant ship. This attempt failed and he moved in with his friend Antonio Meucci (1808 - 1889) on Staten Island, staying for several months in 1850 - 1851. Meucci was an inventor who deserves more fame than he got. Garibaldi returned to Italy and led an army of revolutionaries from Sicily through southern Italy.

The museum was Meucci’s house. It is well worth the $10 price of admission. There are numerous pictures and artifacts, and the docent gave an excellent discussion of both Garibaldi and Meucci. Find out more at https://www.garibaldimeuccimuseum.com/ but go visit. There is far more to learn about both men than can be told here.

A few minutes’ walk from the Garibaldi-Meucci Museum, on Bay Street, is Bayou Restaurant, chock-full of New Orleans stuff. They served us a delicious lunch. I had not been there in almost 20 years, when I was the project manager for the installation of a new signal system on the Staten Island Railway. I was glad they’re still alive, kicking, and serving good food. From there we walked down to the waterfront and on to the Alice Austen House.

Staten Island used to have a busy working waterfront, with shipbuilding and ship repair on the North Shore - some of which still exists - and docks and warehousing along the Narrows. When the U.S. Navy’s four battleships were reactivated in the 1980s, one of them, the Iowa, was based at Stapleton, not far from where we were. Some of the structures on the waterfront are active and some are derelict.

Scene at Sylvaton Terrace and Edgewater Street. Photograph by Michael Cairl.

Walking south on Edgewater Street toward the Alice Austen House, we came upon a waterfront promenade named for a local soldier killed in the Vietnam War, Matthew Buono, and sweeping views of New York Harbor.

Looking from the Matthew Buono memorial toward Brooklyn (top) and the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge (bottom). Photographs by Michael Cairl.

Alice Austen (1866 - 1952) was a photographer and native Staten Islander, not just a pioneering female photographer but a pioneering photographer and pioneering woman. Her home, Clear Comfort, was built in 1690 as a one-room Dutch farmhouse. In 1844 it was purchased by John Haggerty Austen, Alice Austen’s grandfather. It sits upon a slight, well-shaded rise above the Narrows, a beautiful spot now to visit and once to have lived. Austen photographed streetscapes, landscapes, scenes of the harbor, and ordinary working people. One can draw a line from her work to that of later photographers such as Berenice Abbott (1898 - 1991) and Helen Leavitt (1913 - 2009). To this longtime amateur photographer, Austen’s eye and sensitivity were remarkable. I could have spent hours going through the library of her prints, and I will go back specifically to do so.

Parlor in the 1844 addition to the house. Photograph by Michael Cairl.

Images of the Quarantine Station on Hoffman and Swinburne Islands, man-made islands from the 19th Century to seaward of the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge. Photograph by Michael Cairl.

About Austen, from the website https://aliceausten.org:

Austen was independently wealthy for most of her life and has widely been considered an amateur photographer because she did not make her living from photography. However, in addition to completing a paid assignment documenting the people and conditions of immigrant quarantine stations in New York during the 1890s, Austen copyrighted, exhibited and published her work.

Alice Austen’s life and relationships with other women are crucial to an understanding of her work. Until very recently many interpretations of Austen’s work overlooked her intimate relationships. What is especially significant about Austen’s photographs is that they provide rare documentation of intimate relationships between Victorian women. Her non-traditional lifestyle and that of her friends, although intended for private viewing, is the subject of some of her most critically acclaimed photographs. Austen would spend 56 years in a devoted loving relationship with Gertrude Tate, 30 years of which were spent living together in her home which is now the site of the Alice Austen House Museum and a nationally designated site of LGBTQ history.

Austen’s wealth was lost in the stock market crash of 1929 and she and Tate were finally evicted from their beloved home in 1945. Tate and Austen were separated by family rejection of their relationship and poverty. Austen was moved to the Staten Island Farm Colony where Tate would visit her weekly. In 1951 Austen’s photographs were rediscovered by historian Oliver Jensen and money was raised by the publication of her photographs to place Austen in private nursing home care. On June 9, 1952 Austen passed away. The final wishes of Austen and Tate to be buried together were denied by their families.

One of the images above is about the quarantine station on Hoffman and Swinburne Islands. A quick sidebar on these, from The Other Islands of New York City: A History and Guide, Second Edition by Sharon Seitz and Stuart Miller (The Countryman Press, 2001):

Staten Islanders had had enough. In 1858, after more than fifty years as New York’s dumping ground for people with deadly, contagious diseases - yellow fever, typhus, cholera, and smallpox - infuriated mobs burned the New York Quarantine Hospital to the ground. In the face of this unsurpassed expression of NIMBY-ism, the government was forced to create two artificial islands, Hoffman and Swinburne, to house the ill.

These islands, to seaward of the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge, are now part of the Gateway National Recreation Area and are home to migratory birds. For years in the 1970s, the Cunard liner Caronia was abandoned, at anchor off Hoffman Island, a ghostly presence.

Profile of this walk, readiing from left to right.

This walk was yet more proof of the fascinating things to be found in this city when one ventures beyond the well-trod tourist trail. It was a good walk with fascinating places visited, a good stair street, a fine lunch, all with good company. Onward!

Bayonne Bridge

WHERE: The Bayonne Bridge, from Staten Island, New York to Bayonne, New Jersey.

START: Innis Street and St. Joseph Avenue, via S46 bus from St. George Ferry Terminal.

FINISH: 8 Street station, Hudson-Bergen Light Rail (fully accessible)

DISTANCE: 2.3 miles (3.7 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl. Map courtesy footpathapp.com.

Bike racks and tire pump at the Staten Island end of the bridge.

I picked a very pleasant day for this walk, with low humidity, a refreshing breeze, and high temperature of 26C (79F). The Bayonne Bridge, which opened in 1931, was the longest steel arch span in the world at the time of its construction and remained so for many years. It spans the narrow Kill van Kull that links Newark Bay and the huge container terminals at Port Elizabeth and Port Newark to New York Harbor. With the addition of a new, larger set of locks at the Panama Canal, “post-Panamax” container ships, those larger than could be accommodated by the original Panama Canal locks, could reach the Port of New York and New Jersey but for insufficient vertical clearance at the Bayonne Bridge. In recent years the roadway was raised some 50 feet (16 meters) to allow greater vertical clearance, the work being completed in 2019. The original steel arch was left intact but the roadway, being suspended from the arch on cables, was raised up. A new, much wider bike and foot path was built on the east side of the bridge, replacing the old path on the west side. For a nice, succinct history of this bridge go to https://www.panynj.gov/bridges-tunnels/en/bayonne-bridge/history.html.

I had biked across the bridge twice in the early 1990s, both times from Bayonne to Staten Island. This was my first time crossing on foot and going in the opposite direction. I don’t recall ever driving over the bridge.

The start of this walk was in the modest Elm Park neighborhood on Staten Island’s north shore, a microcosm of a much more diverse place than Staten Island is often thought to be. With the roadway being raised the ascent was steep but not too tiring. Along the way were interpretive posters about the waterway, the economy of the area, the construction of the bridge, and the ecology of the area. Not being in a hurry, I took time to read each of them. Three examples are in the following images.

The bridge itself is impressive and the views from the bridge were remarkable.

From mid-span on the bridge: Bayonne at left, Staten Island at right, the towers of Manhattan and Brooklyn in the distance.

Bayonne Bridge at mid-span.

Beyond the bridge, the Port Newark container terminal.

The end point was a short walk from the north end of the Bayonne Bridge, the southernmost point on New Jersey Transit’s Hudson-Bergen Light Rail, the 8 Street station. This was once a terminus for passenger trains on the Central Railroad of New Jersey. A handsome station building recalls the old, long since demolished Jersey Central station. I took the light rail to Exchange Place in Jersey City where I transferred to the PATH train to the World Trade Center, then to the subway for the trip home.

8 Street station, Hudson-Bergen Light Rail.

This was a fine walk, a long time in the works. I’m glad I picked a picture-perfect day for it. It was good to get farther than usual from the tourist trail, to see an engineering marvel adapted to changing times and made inviting for bicyclists and pedestrians. The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey did a nice job with this. You can see the detailed route of this walk at https://footpathapp.com/routes/8c1fab62-fa12-4d1e-9495-5aa544ab0ccc.

Map of this walk, reading from bottom to top.

To the Henry Hudson Bridge and Beyond

Henry Hudson Bridge in background.

WHERE: Inwood neighborhood of Manhattan, the Henry Hudson Bridge, and the Spuyten Duyvil and Kingsbridge neighborhoods of the Bronx.

START: Dyckman Street subway station (1 train, partially accessible)

FINISH: 238 Street subway station (1 train)

DISTANCE: 3.5 miles (5.6 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl and Keith Williams. Video and voice-over by Keith Williams. Maps courtesy Google Maps.

Route of this walk, reading from bottom to top.

Profile of this walk, reading from left to right.

The Henry Hudson Bridge is a high arch span over the Harlem River, just east of where it meets the Hudson River. There’s a walkway on the west side of the lower level of the bridge, accessible by local streets on the Bronx side and by a steep path through Inwood Hill Park on the Manhattan side. I hadn’t walked across the bridge in more than 25 years and wanted to do so again, in part to prove I could climb that slope on the Manhattan side (highlighted in red on the accompanying map).

On this low-humidity day I was joined by my friend Keith and his friend Cat. We set out from the Dyckman Street station of the 1 train. This station, dating from 1906, emerges from the deepest tunnel in the subway system. There is an elevator to the downtown platform; an elevator to the uptown platform is under construction. Dyckman Street is a busy commercial thoroughfare in a crazy-quilt multi-ethnic neighborhood; we walked northwest toward the Hudson River and Inwood Hill Park. There we walked along the river toward the footbridge over Amtrak’s Empire Line and the path to the Henry Hudson Bridge, enjoying a refreshing breeze along the river.

View of the Hudson River and the New Jersey Palisades from the Inwood Hill Park trail.

Footbridge over the Amtrak line, 46 steps up.

The footpath to the bridge continues from the east end of the footbridge over the Amtrak line. This is the route Amtrak uses for trains between New York and Albany, part of one of the most scenic train rides in America, along the Hudson River. The footbridge has 46 steps and is in good condition. At the east end of the footbridge we were greeted by a gentleman, older than I, who said he had recently walked from Kappock Street, near the Bronx end of the bridge, to Houston Street in Manhattan, about 13 miles (21 kilometers). Outstanding!

The footpath to the bridge is in very good condition and is well-shaded but it is steep. Steep hills are more difficult for me than stairs. I walked with care and was glad I had company for this part of the walk in particular. I was confident I could make it all the way to the bridge footpath and I did, feeling a nice sense of accomplishment at the top.

In the words of Yogi Berra, when you see a fork in the road, take it. The path to the right leads to the bridge; the path to the left leads under the bridge and to the east side of Inwood Hill Park.

The summit! The south end of the Henry Hudson Bridge.

View from the Henry Hudson Bridge of Amtrak’s Spuyten Duyvil drawbridge, the Hudson River, and the New Jersey Palisades. Compare with the previous image taken from river level. At mid-span the lower level of the bridge is 135 feet above mean high water.

The bridge footpath ends with 8 steps down to the frontage (service) road of the Henry Hudson Parkway. From there we went to nearby Henry Hudson Park, the centerpiece of which is a classical column that is a memorial to the navigator Henry Hudson. From urban archive.org:

During the Hudson-Fulton Celebration of 1909 (commemorating the 300th anniversary of Hudson's arrival and the centennial of Fulton's steamboat) a plan was developed to honor Hudson with a memorial. Land was donated, funds were amassed, architects Babb, Cook and Welch designed a 100-foot-high Doric column, and sculptor Karl Bitter began to model his statue of Hudson. The column was erected in 1912 but the project stalled in 1915 with low funds and the death of Bitter.

In 1935, Parks Commissioner Robert Moses revived the monument plans as part of his Henry Hudson Bridge and Park project. Karl H. Gruppe, one of Bitter's students, created the statue which was finally placed on top of the 25-year-old column and dedicated in January of 1938.

History has been rightly unkind to Robert Moses (1889 - 1981), New York’s “master builder,” but we all walk this earth leaving a mixed legacy. This was one of his good works.

Yours Truly approaching the West 232 Street stairs.

The rest of the walk took us along some semi-suburban blocks leading to the West 232 Street stairs (60 steps down) and the Manhattan College stairs (120 steps down), both described in my post “Over Hill and through More of Riverdale” on “The Stair Streets of New York City” page, punctuated by lunch at an Irish establishment called An Beal Bocht (Irish for The Poor Mouth), from the novel of the same name by by Irish author Flann O’Brien. From the cafe’s website: “Set in a remote region in Ireland, the fictional memoir discusses life, language, and abject poverty in Ireland. It is considered one of the greatest Irish-Language novels of the 20th Century,”

This was an outstanding walk on a fine day. The climb up to the Henry Hudson Bridge was a physical and mental challenge and I’m glad to have done it. Having good company made it better. I’ll be back to Inwood Hill Park and the bridge soon.

Inside An Beal Bocht Cafe.

Here’s a video of me descending the Manhattan College stairs:

STAIR COUNT: 46 up, 188 down, total 234 (not counting subway stations).

ONWARD!

Harlem and Heights History Walk (Manhattan)

WHERE: Harlem, Harlem Heights, Sugar Hill, and Washington Heights, Manhattan

START: 135 Street subway station (2 and 3 trains, fully accessible)

FINISH: 168 Street subway station (A and C trains, fully accessible)

DISTANCE: 2.6 miles (4.2 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl and, where noted, by Matt Summers.

Route and profile of this walk, reading from bottom to top. Map courtesy footpathapp.com.

History is all around us in this city, and I mapped out this walk to include a good chunk of history, much of which hides in plain sight. My friend Matt and I met for this walk in front of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, an important research unit of The New York Public Library. From the NYPL website:

Founded in 1925 and named a National Historic Landmark in 2017, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture is one of the world’s leading cultural institutions devoted to the research, preservation, and exhibition of materials focused on African American, African Diaspora, and African experiences. As a research division of The New York Public Library, the Schomburg Center features diverse programming and collections spanning over 11 million items that illuminate the richness of global black history, arts, and culture.

Established with the collections of Arturo Alfonso Schomburg [97] years ago, the Schomburg has collected, preserved, and provided access to materials documenting black life in America and worldwide. It has also promoted the study and interpretation of the history and culture of people of African descent. In 2015, the Schomburg won the National Medal for Museum and Library Service and in January 2017, the Schomburg Center was named a National Historic Landmark by the National Park Service, recognizing its vast collection of materials that represent the history and culture of people of African descent through a global, transnational perspective. Today, the Schomburg continues to serve the community not just as a center and a library, but also as a space that encourages lifelong education and exploration.

For much more information about this special place go to https://www.nypl.org/about/locations/schomburg.

Across Lenox Avenue from the Schomburg Center is the Harlem Hospital Center, a major “safety net” hospital for the community. We walked up to and west on West 137 Street, past Mother African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church. Founded in 1796, this is the oldest A.M.E. Zion congregation. “Mother Zion” has been at this location since 1925, the building having been designed by the early African-American architect George W. Foster, Jr. From there we went around the corner to West 138 Street to have a look at Abyssinian Baptist Church. From The AIA Guide to New York City, Fifth Edition:

Random ashlar "Collegiate Gothic" (the building would be at home at Princeton or Yale), doubly a landmark in Harlem due to the charisma, power, and notoriety of its spellbinding preacher, Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. (1908-1972), 14-term member of the House of Representatives. The church has established a memorial room, open to the public, containing artifacts from his life. Call before you visit.

From Abyssinian Baptist we walked west past Strivers’ Row. These row houses occupy the full block of West 138 Street to West 139 Street, from Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard to Frederick Douglass Boulevard. These were built between 1891 and 1893 as the King Model Houses, to the designs of some of the leading architects of the time, among whom was Stanford White. Again from The AIA Guide to New York City, Fifth Edition:

Despite Harlem's ups and downs, the homes and apartments retained their prestige and attracted (by 1919) many successful blacks in medicine, dentistry, law, and the arts such as W.C. Handy [232 W. 139], Noble Sissle, Fletcher Henderson [228 W. 139], Eubie Blake, and architect Vertner Tandy [221 W. 139]. As a result, Strivers' Row became a popular term for the district in the 1920s and 1930s.

From the WPA Guide to New York City (1939):

West 138th and 139th Streets, between Seventh and Eighth Avenues, are known in Harlem as STRIVERS' ROW because so many Negroes aspire to live in the attractive, tan-brick houses on these two tree-shaded streets. The residents are mostly of the better-paid, white-collar and professional class; some rent furnished rooms in order to meet the comparatively high rental. The 130 dwellings were designed by Stanford White and erected shortly before the Negroes came to Harlem. The most interesting section of the row is the north side of 139th Street. Here dark brick and terra·cotta facades enriched with wrought-iron balconies and delicate entry porch roofs, were designed with considerable artistry in the spirit of the Florentine Renaissance.

When built, these houses were not open to “Negroes.”

Unusually for Manhattan, these houses include an alley in the rear, originally for keeping horses. In the second image below, note the sign on the pillar: PRIVATE ROAD WALK YOUR HORSES.

Across West 138 Street is a small church that had me wondering about its origins. Again, the AIA Guide provides an answer:

Victory Tabernacle Seventh Day Christian Church/ formerly Coachmen’s Union League Society of New York City. 252 W. 138th St., bet. Adam Clayton Powell. Jr. Blvd. and Frederick Douglass Blvd. 1895-1896. … It was built to sell life insurance to residents of this newly opened "suburb” of Harlem, particularly to those living in the King Model Houses.

Row houses in the Dorrance Brooks Square Historic District.

Continuing across Frederick Douglass Boulevard we came upon the Dorrance Brooks Square Historic District and row houses that would be right at home in my neighborhood in Brooklyn. It is named after Dorrance Brooks (1893-1918), an African-American soldier who died while serving in the segregated military during World War I. He was a member of the 369th Infantry Regiment, better known as the Harlem Hellfighters. The area is a residential neighborhood consisting mostly of Renaissance Revival- and Queen Anne-style row houses built in the late 19th and early 20th century. The district was home to many notable African American thinkers, artists, actors and doctors during the Harlem Renaissance (1920s-1940s), including intellectual W.E.B. DuBois, performer Ethel Waters and sculptor Augusta Savage. (Source: https://www.thecuriousuptowner.com/post/get-to-know-beautiful-dorrance-brooks-square-harlem-s-proposed-new-historic-district.)

At this point Matt and I were by no means done with our history walk. We walked up St. Nicholas Avenue and west up the steep hill of West 141 Street, to Hamilton Grange, the home of Alexander Hamilton, 1776 graduate of King’s College (now Columbia University), one of the authors of the Federalist Papers and the first Secretary of the Treasury. The Grange was completed in 1802 and Hamilton’s enjoyment of it was short, as he was killed in a duel with Vice President Aaron Burr two years later.

Hamilton Grange. Photograph by Matt Summers.

From the Grange we crossed West 141 Street and walked up Hamilton Terrace, past more fine row houses to West 144 Street and then to Convent Avenue. Convent Avenue north of City College is tree-shaded and has many fine row houses. I’ve described this area in a previous post, “Hamilton Heights, Sugar Hill, Polo Grounds” on the “The Stair Streets of New York City” page.

We continued north along Convent Avenue, West 150 Street, and St. Nicholas Terrace to the Harlem River Driveway and the John T. Brush Stairway across from the site of the Polo Grounds stadium, demolished in 1964. See a fuller description in the aforementioned post. Up the 96 steps we went to Edgecombe Avenue. This is Sugar Hill, so named because life was sweet up there. Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Lena Horne, and Paul Robeson were among the many famous people who lived on or near Edgecombe Avenue. We turned onto West 160 Street and another steep hill to the Morris-Jumel Mansion (1765). This was built as a country estate by Roger Morris (1727 - 1794), a colonel in the British Army, for himself and Mary Philipse, middle daughter of Frederick Philipse, second Lord of the Philipsburg Manor. She owned a one-third share of the Philipse Patent, a vast landed estate on the Hudson River which later became Putnam County, New York. (Source: Wikipedia).

Corner of the Morris-Jumel Mansion. Photograph by Matt Summers.

Lithograph of Madame Jumel, 1852.

The mansion served briefly as George Washington’s headquarters in 1776 after his army fled Brooklyn, when it was retreating from Manhattan. The British would occupy what is now New York City for the rest of the Revolution. As the Morrises were Loyalists (to the British Crown), their lands, including this house, were seized by the revolutionary government of the Colony of New York and sold to pay war debts, and for a time afterward the house was an inn and tavern, conveniently located near the Albany Post Road. In 1810 the house was bought by Stephen Jumel, a wealthy Frenchman, for himself and his wife, the former Eliza (Betsey) Bowen (1775 - 1865), who grew up in a brothel in Providence, Rhode Island. The Jumels were not accepted socially in New York. After Jumel’s death under suspicious circumstances, Eliza inherited this house and his large fortune, and shortly after Jumel’s death married Aaron Burr. (Perhaps it is more correct to say he married her.)

The house is on a tree-shaded plot on one of the highest points in Manhattan and is open to the public.

From there we crossed Jumel Terrace to walk along Sylvan Terrace, described in the post “Sylvan Terrace” on “The Stair Streets of New York City” page and from there walked to the last stop on this tour, West 165 Street and Broadway. This building, the former Audubon Ballroom, lay derelict for years until Columbia University acquired it and built a new interior behind a restored façade. The Audubon Ballroom was where Malcolm X was assassinated in 1965. Born Malcolm Little, he was a vocal advocate for black empowerment and the promotion of Islam within the black community. History is all around us, in plain sight. The building now houses the The Malcolm X & Dr. Betty Shabazz Memorial and Educational Center (Betty Shabazz was Malcolm X’s wife). This area is now dominated by Columbia’s Health Sciences Campus and the various parts of Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center. Presbyterian Hospital is on the site of the former Hilltop Park, the home of the New York Yankees (formerly the Highlanders) until 1920. Columbia’s College of Physicians and Surgeons is the oldest medical school in the United States and predates the Revolution.

Former Audubon Ballroom. Photograph by Matt Summers.

In less than three miles we traversed a lot of history, and with the hills and stairs I got in some good physical therapy. As with all my favorite walks around this city, all of it was well off the tourist trail. I recommend this walk to anyone.

Sometimes I Stumble

Bayside station’s accessibility is with ramps, not elevators, eliminating a maintenance headache.

WHERE: Crocheron Park, Bayside, Queens

START/FINISH: Bayside station, Long Island Rail Road (Port Washington Branch, fully accessible)

DISTANCE: 1.9 miles (3.1 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl and Jordan Centeno. Map courtesy Google Maps.

I advertised this trip as a walk along the Joe Michaels Mile foot and bike path along Little Neck Bay to Fort Totten in eastern Queens. My friend Jordan and I set out from the Bayside train station along Bell Boulevard, Bayside’s commercial spine and restaurant row, to Crocheron Park, from which we would take the footbridge over the Cross Island Parkway to the foot path. I didn’t know beforehand that the footbridge was accessible only from within the park. At the end of 35 Avenue there is a steep staircase without handrails up into the park. I remembered that we had passed a shallower set of steps, also without handrails, so we backtracked to and climbed those.

A short distance from the top of the stairs I stumbled on some uneven pavement and fell on my left side, right onto my metal water bottle (it wasn’t hurt), giving me some bruised ribs and “road rash” on my left hand. When I was able to get up, Jordan and a passerby helped me up and onto a nearby bench, and Jordan cleaned up my road rash. Slowly we made our way out of the park to Bell Boulevard and the local bus to a lunch of some great Greek food at Taverna Kyklades.

Map of this walk. X marks the approximate spot where I fell.

I’m glad I didn’t do this walk by myself. It’s more fun to go on these treks around the city with someone, and I could not have got up by myself after falling. Some takeaways from this walk:

I’m grateful for everyone who has ever joined me on a walk.

Since I’m more likely to fall on my weaker left side, wear my water bottle sling on my right side.

I need to be ever mindful of where I walk, going at a safe pace and remembering to lift my feet.

Parks Department, add handrails to those stairways.

Early on in stroke recovery I realized that every day was not going to be better than the day before, so I had to focus on the trend, not fret over the day-to-day, and take my positives when I can. That perspective is just as valid today as it was then.

On our way to Crocheron Park we passed Corporal Stone Street and a street co-named for Geri Cilmi. Wondering who these people are or were, I had to look them up. From a contributor to Kevin Walsh’s great website Forgotten NY (https://forgotten-ny.com/2008/06/bayside-part-1-queens/):

Charles B. Stone was killed on the front lines in France on October 30, 1918. He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery. He was my father’s uncle. His mother, Augusta Wheeler Stone, and sister, Marion Stone, lived in Bayside. Augusta Stone was a long-time member of the Altar Guild at All Saints Episcopal Church in Bayside. My father, Charles Edmund Wolcott, was the son of Marion, Charles B. Stone’s sister, and Edmund Wolcott.

I think Charles B. Stone was employed as a courier on Wall Street before enlisting in the Army and was a Junior Member of the Bayside Yacht Club. He was only about 20 years old when killed.

Geri Cilmi was a longtime science teacher at Public School 41 and seems to have been a remarkable person I wish I had known. A story about her is at https://qns.com/2014/06/street-to-be-co-named-for-bayside-teacher-who-died-from-cancer/. From that post: “Former P.S. 41 science teacher Geri Cilmi’s motto to her students in the Bayside school was ‘You get what you get, and you don’t get upset.’”

One day soon my ribs won’t hurt and I’ll be back exploring the city, chastened and slowed down a bit. I often forget that stumbling and falling is part of my journey in recovery and in life. I might not like this but I’m allowed to stumble and fall. Onward!

The Museum Steps and Other Things in Philadelphia

WHERE: The “Rocky Steps” and other places in Center City (downtown) Philadelphia

START: 30 Street Station (Amtrak, SEPTA, NJ Transit; fully accessible)

FINISH: Jefferson Station (SEPTA Regional Rail; fully accessible)

DISTANCE: 4.1 miles (6.6 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl and a gentleman at the Museum Steps named Andrew. Map courtesy Google Maps.

Route of this walk, reading from left to right.

What might have been an offhand comment by my work colleague Don Brandt got me thinking about climbing the grand staircase at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, made famous in the movie “Rocky.” As luck would have it, Amtrak had one of their occasional fare sales at the time. With a cut-price ticket in hand, off I went. I had not been in Philadelphia since before the stroke.

Upon arriving in Philadelphia, I crossed the short bridge over the Schuylkill (pronounced school-kill) River to the ramp and 35 stairs leading down to the Schuylkill Banks bike and foot path along the river. Although it was the day before the official start of Spring, it was a warm, pleasant day, and a lot of people were out on the path on two feet or two wheels.

Approaching the Philadelphia Museum of Art, I went up 24 steps to Spring Garden Street, then made my way to the base of the Museum steps. Running up these steps is a popular thing to do, recreating a scene from the movie “Rocky” where Sylvester Stallone runs up the steps to the top and raises his arms. Off to the side of the steps is a life-size statue of Stallone with his arms raised. Tourists lined up to be photographed there.

The challenge of the steps is not the number (72) as much as the absence of a handrail. Going up and going down, I got off to a slow start until I got the hang of the stairs and the use of my cane as my sole support. When I got to the top I felt I had really accomplished something. A fellow named Andrew offered to take pictures of me, which I accepted, and then I descended the stairs. The descent was more difficult than the ascent but I made it.

Boathouse Row. The outlines of the buildings are illuminated at night; this is a fine sight from Amtrak trains just north of 30 Street Station.

From there I walked toward Boathouse Row, past the Azalea Garden, and down the Benjamin Franklin Parkway toward City Hall, passing the Rodin Museum, the Barnes Foundation, and the Franklin Institute along the way. I ended my walk at the outstanding Reading Terminal Market and Jefferson Station for the short train ride to 30 Street Station and the train back to New York.

The forecourt of the Rodin Museum, the Shakespeare Memorial across from the Free Library, entrance to the Reading Terminal Market, historical marker across from City Hall.

This was a day very well spent. I’ll surely come back before too long to revisit several museums and discover new things in the City of Brotherly Love.

Stair recap: 96 up, 107 down, total 203.

The Bronx and Pelham Parkway (Bronx)

Route of this walk, reading from right to left.

WHERE: Along and near Pelham Parkway, Bronx

START: Pelham Bay Park subway station (6 train, fully accessible)

FINISH: Pelham Parkway subway station (2 train, fully accessible)

DISTANCE: 3.0 miles (4.8 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl except as noted. Maps courtesy Google Maps.

The Bronx and Pelham Parkway - nobody calls it anything but Pelham Parkway - was built as a linear park to link Bronx Park and Pelham Bay Park, hence the name. Land for the parkway was acquired in 1884 and in the following years it acquired its present form. From Boston Road to Stillwell Avenue it is over 200 feet (61 meters) wide with four roadways separated by wide green spaces. There’s a well used bike and pedestrian path that I’ve biked many times but never walked until today, that is in fair condition but should be rebuilt with an even surface and proper drainage. It is part of the East Coast Greenway. I found the idea of walking along Pelham Parkway appealing, and chose a mild day to do so. I was able to put together a fully accessible route, including the subway stations at either end.

I started at the elevated Pelham Bay Park subway station, where there is a spur to the main Pelham Parkway bike trail. At Stillwell Avenue, just west of where the parkway crosses Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor, the bike/pedestrian path switches from the south side of the parkway to the north side. Between Stillwell Avenue and Eastchester Road, on Pelham Parkway North, is a house that for decades has had a year-round display of Christmas and other stuff. I remember being astonished by the sight when I first biked past it in the late 1980s. It is still quite a sight.

Profile of this walk, reading from left to right.

The route is a gentle but steady uphill from Stillwell Avenue to Williamsbridge Road, where I turned off and where there is a small triangle called Peace Plaza. It is dedicated to, and was clearly the vision of, the late Rudy Macina, a pillar of the local community. Peace Plaza honors the dead from the two World Wars, the Korean and Vietnam wars, the 1991 Persian Gulf campaign, and the attacks on September 11, 2001. I stopped to look around there and continued on toward a local Roman Catholic shrine, the Our Lady of Lourdes grotto, part of St. Lucy’s Church. Reflecting its neighborhood, St. Lucy’s offers masses in English, Spanish, Italian, and Albanian. I sat on one of the benches outside for a few minutes, watching the faithful come and go, many of them carrying bottles or jugs with which to take home holy water. Lourdes of America in the Bronx - and I thought my native Brooklyn is the land of miracles. Before arriving there I had a tasty lunch at a tiny Albanian restaurant on Mace Avenue, where Mama did the cooking and her teenage son served. I’ll surely be in the area, and there, again. From the shrine I walked to the end point, the elevated subway station at Pelham Parkway and White Plains Road.

This is an area that 100 or so years ago was semi-rural. Today the area is largely low-rise and semi-suburban, with a few higher-rise buildings such as health care facilities and the New York City Housing Authority’s Pelham Parkway Houses. This was a satisfying, interesting walk through yet another untouristed part of the city with its own genuine, not manufactured, vitality. (Sorry, Times Square.) A short distance west of today’s end point is the Bronx Zoo, and just past there is the New York Botanical Garden. This walk was also worthwhile as it was 100 percent accessible. I recommend it highly. If you don’t want to do the whole walk, consider starting or finishing at the Pelham Parkway station on the 5 train (not accessible) or by taking a bus on Williamsbridge Road, Eastchester Road, or Pelham Parkway.

The Garabedian Family Christmas House. Looking south on Eastchester Road, 1924 (image courtesy New York Institute for Special Education) and 2022.

Peace Plaza.

Where I had lunch, view of the Our Lady of Lourdes Grotto, and sign showing the diversity of the community served by St. Lucy’s Church.

Pelham Parkway west of Eastchester Road (it’s wider than it looks) and two views of the trail (spur from Pelham Bay Park subway station, and near Throop Avenue).

Some more “then and now:” Pelham Parkway North, 1923 (image courtesy New-York Historical Society) and 2022.

New Life for Old Railroad Stations in the Bronx

This item in The New York Times is an excellent look at initiatives to restore and reuse three stations built in the Bronx over 100 years ago. For some context read my post “Lower Bronx River Greenway” on this page. It is very encouraging to see the distinct possibility of adaptive reuse of these buildings.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/28/realestate/cass-gilbert-train-stations-bronx.html?smid=url-share

Bushwick and a bit of Ridgewood (Brooklyn)

WHERE: Some of the western part of Bushwick and a bit of Ridgewood, Brooklyn

START: Jefferson Street subway station (L train)

FINISH: Seneca Avenue subway station (M train)

DISTANCE: 1.4 miles (2.25 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl. Maps courtesy of Google Maps.

Route of this walk, going from left to right.

This was a spur-of-the-moment trip following most of a route I mapped out some time ago. The western part of the Bushwick neighborhood is an old industrial and warehousing area that still has a lot of those activities and has been discovered by artists and (I loathe this term) “hipsters.” For starters, I wanted to say hello to my friends Paul and Sarah, who are the creators of Kings Kolache at 321 Starr Street, at Cypress Avenue. Kolaches are Czech breads; Paul and Sarah make them with a Texas twist. Find out more at https://www.kingskolache.com/. They weren’t in but their associate Colin let them know I had been by. Undaunted, I walked a few blocks to the VanderEnde-Onderdonk House, a Dutch farmhouse built in 1709, on Flushing Avenue. This little museum, maintained by the Greater Ridgewood Historical Society, is fascinating and well worth a visit. The VanderEnde and Onderdonk families lived here for over 200 years. It used to sit on a farm of some 50 acres (20 hectares). The house is open only on Saturday and Sunday afternoons but do go for a fascinating look at a piece of Brooklyn’s history. More information is at https://onderdonkhouse.org/.

Three views of the VanderEnde-Onderdonk House, part of one of the exhibits, and the parlor of the house.

Will of Paulus VanderEnde dated January 17, 1722, written in Dutch, witnessed by his neighbors on what is now Flushing Avenue.

From there I walked east on Onderdonk Avenue, a residential area with small shops at several intersections.. I came upon another cathedral for the common people, St. Aloysius Roman Catholic Church, at Stockholm Street. Serving a diverse congregation, this busy church offers Masses in English, Polish, and Spanish.

A few blocks farther on is a much simpler but very attractive church, the Safe Haven United Church of Christ, at Grove Street. I ended the walk at the elevated Seneca Avenue subway station.

Safe Haven United Church of Christ, and the view of Seneca Avenue from the subway station platform, with the towers of Manhattan in the distance.

Profile of this walk.

This wasn’t a long walk but it was a rewarding one, in an area in which I’ve done very little walking but will happily do more.

The Putnam Trail (Yonkers and The Bronx)

Route of this walk.

WHERE: The very southern end of the South County Trail in Yonkers, which becomes the Putnam Trail in Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx.

START: McLean Avenue and Tibbetts Road, Yonkers (Bee-Line number 4 bus from Woodlawn subway station - 4 train)

FINISH: 238 Street subway station (1 train)

DISTANCE: 2.7 miles (4.3 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl. Maps courtesy of Google Maps.

Profile of this walk.

Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx is bisected by the Putnam Trail, following the route of the old Putnam Division of the New York Central Railroad. Passenger trains ran on the “Put” until 1958 to Brewster, New York and occasional freight service continued until 1980. Like passengers on the New York, Westchester & Boston, passengers on the Putnam Division (except for electric trains on the Getty Square branch, abandoned in 1943) could not go through to Grand Central Terminal, having to transfer at the Sedgwick Avenue terminal in the Bronx to trains to Grand Central or to the Ninth Avenue elevated. In 1940 the latter was reduced to a shuttle from the Polo Grounds to the 167 Street subway station. The Polo Grounds shuttle was discontinued in 1958 after the New York Giants baseball team moved to San Francisco at the end of the 1957 season, a few months before the end of passenger service on the “Put.” The route from the New York City limits was paved over time, giving a bike and pedestrian path that is a continuous trail from the Bronx to Brewster except for a couple of diversions onto local roads. Once, in 2010, I biked the whole length of the trail. It is a beautiful ride even with about 25 miles (40 kilometers) of gentle but steady uphill from Elmsford to Baldwins Place. The Putnam Trail is part of the Empire State Trail, a 750-mile long system of bike paths, on-road bike routes, and canal towpaths running north to south and east to west across the State of New York.

One of a series of stained glass windows at the Woodlawn subway station, the series entitled “Children at Play.”

Until about a year ago the portion of the trail in Van Cortlandt Park was unpaved. Much of the trail became muddy after a little rain, and north of Van Cortlandt Lake the trail was a narrow path hemmed in by vegetation and railroad ties. Years of planning to pave it were accompanied by years of protests and hand-wringing, until finally it was paved. I had not seen the paved trail, so I set out to walk it. On an unseasonably warm day I was accompanied by Ken, who joined us last week on the East Bronx Ramble (see “The Stair Streets of New York City”).

It is a few minutes’ bus ride from the Woodlawn subway station to McLean Avenue and Tibbetts Road, just a short walk from the trailhead where one can go north toward Brewster or south toward the Bronx. The trailhead is accessible from a short street, Alan B. Shepard Jr. Place, named after the second person and first American to go into space, in 1961. I don’t know that Shepard had any connection to the city of Yonkers.

The approach to the trailhead, the trailhead, and looking to the north from the trailhead, with the Saw Mill River Parkway, the trail, and Tibbetts Brook.

The paved trail is excellent for walking, running, or biking. It goes past the Van Cortlandt Park golf course, the oldest public golf course in the United States.

Two views of the trail at the City line, the trail passing the golf course (on left), the upper reach of Van Cortlandt Lake and a wetland just beyond, created by the damming of Tibbetts Brook over 100 years ago.

Near the southern end of the trail is an unusual grouping, the Grand Central Stones. These came from different quarries in 1905 to evaluate their suitability for the new Grand Central Terminal that opened in 1913. Exactly why the New York Central Railroad placed them here, of all places, is anybody’s guess, but they are a surprise on the trail, accompanied by an excellent interpretive sign.

As seen on Bailey Avenue.

The end of the walk took us across Van Cortlandt Park South and south on Bailey Avenue, then west on West 238 Street to the Bronx Ale House for lunch and then to the subway. This was an easy but fun walk, and I’m glad to have seen the newly paved Putnam Trail in Van Cortlandt Park.

Off-roading on Staten Island

WHERE: The Staten Island Greenbelt, mostly

START: New Dorp station, Staten Island Railway

FINISH: Joe & Pat’s Restaurant, Victory Boulevard at Manor Road, then S62 bus to St. George Ferry Terminal

DISTANCE: 5.19 miles (8.31 kilometers)

Maps by Google Maps and Carl Bombara. Photographs by Carl Bombara except where noted.

A few years ago my friends Rob and Kristin told me about an excellent pizza restaurant on Staten Island called Joe & Pat’s. I had not been on Staten Island in about 10 years and wanted to do a walk there, I wanted to go to Joe & Pat’s, and my good friend Carl lives on Staten Island, so it was time to plan a walk. Working with Google Maps, I mapped what looked like a good hill-climbing walk. Carl met me at the New Dorp train station and off we went.

The Staten Island Railway is an oddity. Once upon a time, fares were collected aboard the train; now, fares are collected only at the St. George Ferry Terminal and Tompkinsville station, On the rest of the line, one can travel between stations at no charge. The railway dates from the 1860s and was once owned by the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad. In 1925 the B&O electrified the line and placed subway-type cars in service. The Metropolitan Transportation Authority acquired the line around 1971, and in 1973-74 delivered new subway cars for the line that are still in service today. As a sidebar, from 2002-2004 I was the project manager for the introduction of a modern signal system on the line.

New Dorp’s commercial strip, New Dorp Lane, is centered on the train station and has many shops and restaurants. The station is one of 10 subway and Staten Island Railway stations that are in the process of being made accessible, though work has yet to start at New Dorp.

Starting out, the walk was uneventful, along streets. When we got to High Rock Park we found an unmarked trail and ended up walking the first of several near-circles. No colored blazes on the trees or anything else, even though the Google Maps called out the “Yellow Trail” for the entire distance in the park. Thankfully, Carl took on the role of navigator. We walked along several trails, some of then marked, but the markings were rarely yellow. The trails had little wooden bridges here and there fording streams. Some of the trail walking was very steep and it was mostly unpaved. I had to tread carefully and with help lest I trip and fall because of a rock or a tree root. Eventually we found an outlet to Manor Road, where we would have ended up on the mapped route, and walked for some distance where there was no sidewalk and only a narrow shoulder. And sleet started falling while we were out there. Passing motorists gave us wide berth but I do not recommend walking on that road through the Greenbelt.

The route as mapped versus the route as walked.

This proved to be my most challenging walk by far, on stair streets or not, since the stroke, as well as the longest. The challenge came from the trails not being well-marked and for their being rugged, eroded in many places, and not paved. Tree roots and wet leaves were constant tripping hazards. I am most grateful to Carl for being there, navigating, and making sure I didn’t trip or fall.

As mapped we would have been on Todt Hill, the second-highest elevation on the Atlantic coast after Cadillac Mountain in Maine. We ended up doing a good climb anyway.

If anyone from the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation is reading this, I know your budgets have been cut to the bone over many years, but come on. Somebody please re-mark the trails in the Greenbelt. I’m not kidding. As we approached Manor Road we saw a tree on the left with a blue blaze, then happened to turn around and saw the same tree with a yellow blaze on the opposite side. Grade the trails. Put decent directional maps along the way. And bring someone from Google Maps with you.

All this said, the Staten Island Greenbelt is truly a wonderful place, tranquil and stress-relieving, a far remove from the city. It is astounding to think that the city’s late master planner, Robert Moses (1888-1981), planned a superhighway called the Richmond Parkway to be built through here, connecting the Staten Island Expressway (and the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge) with the Outerbridge Crossing at the southwestern tip of the island. A half-finished interchange to what would have been the Richmond Parkway stood on the Staten Island Expressway for decades until it was demolished during the expressway’s widening.

Carl and me, a pond near the park entrance (photo MC), trail showing a bridge and blue and yellow blazes marking the trail, Manor Road through the park.

We continued to our destination for an excellent cheese pizza. Well-done, thin crust, fresh ingredients. It was a fine reward and I will be back, no question about it. At the end, as we got to Victory Boulevard (renamed from Richmond Turnpike during World War I), Carl remarked that the name was a fitting conclusion to a tough walk. Indeed it was. Thanks, brother, for keeping me going on this walk, which gave me a huge sense of accomplishment.

Therapy Walk (Astoria, Queens)

START: Astoria Boulevard subway station (N train, fully accessible)

FINISH: Ditmars Boulevard subway station (N train)

DISTANCE: 2.1 miles (3.4 kilometers)

Images courtesy of Google Maps except where noted.

Map of today’s walk.

Profile of today’s walk.

Today’s walk was designed to be an event for the stroke support group at New York Presbyterian - Brooklyn Methodist Hospital, of which I am a member. It was an easy walk with only one gentle hill, on Ditmars Boulevard. I was joined by Peter, the leader of the stroke support group.

This was a perfect day for this walk, with sunny skies and a high temperature of 55F/13C. The dog run in Astoria Park was full of happy puppies. From the Astoria Boulevard subway station we walked down to the East River and Astoria Park, then along the riverfront on Shore Boulevard past the Triborough and Hell Gate Bridges to Ditmars Boulevard. As many times as I have biked this route, I had walked only a portion of it once before; see my post entitled “Marching Through Astoria” on the “Stair Streets of New York City” page. Peter and I had lunch at an excellent Greek restaurant, Agnanti, on Ditmars Boulevard and 19 Street, then walked to the elevated subway station on 31 Street at Ditmars Boulevard. This extended the originally planned walk by 0.6 mile (1 kilometer).

I recommend this walk for anyone, not just those with mobility issues. Astoria is a busy, diverse, fascinating neighborhood with a fine restaurant scene.

Hell Gate Bridge and Triborough Bridge (photograph by Michael Cairl); Agnanti Restaurant (photograph courtesy Google).

Central Bronx Mix No. 1

WHERE: Van Nest and Parkchester neighborhoods, the Bronx

START: East 180 Street subway station (2 and 5 trains; fully accessible)

FINISH: Parkchester subway station (partially accessible; escalators from street level to platforms)

DISTANCE: 2.0 miles (3.2 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl

Route and profile of this walk, courtesy Google Maps.

This walk was not particularly physically taxing, it definitely was not scenic, and I knew all that ahead of time having biked these streets in the past. So why did I go there? A work assignment has me developing a work scope for the design of two stations for Metro North Railroad’s Penn Station Access project. This project will have commuter trains operating along Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor from New Rochelle, New York to Pennsylvania Station, with four new stations in the Bronx. One of them will be in the area I walked through today. Not being one to try to do this from my armchair, I had to get out there for a good look. And I coupled that with a look at Parkchester, an interesting residential area.

On the opposite side of the tracks once stood the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad’s main repair shops for electric locomotives and, before that, a thoroughbred race track. The New Haven electrified this line in 1912 and it once had as many as six tracks for both passenger and freight trains. Now it has just two tracks for Amtrak. The old steel bridges carrying the overhead wires that carry the electric power for the trains still stand, and one is visible in the third image below.

Starting at the landmark East 180 Street subway station (look at my post “Lower Bronx River Greenway” for a photo and description), I walked to and along East Tremont Avenue, with the Northeast Corridor tracks on one side and the northern extent of Parkchester on the other. This streetscape is ugly. Enough said. There are plenty of automobile repair places, parking lots, filling stations, a car wash, and a Golden Corral all-you-can-eat buffet. Some of this stretch of East Tremont was part of my bike route from Brooklyn to City Island. I turned off at Castle Hill Avenue, with St. Raymond’s Church at the corner, then turned onto Metropolitan Avenue for the walk through Parkchester.

East Tremont Avenue streetscape.

St. Raymond’s Church, corner Castle Hill Avenue and East Tremont Avenue. Yet another neighborhood cathedral in the Bronx; see St. Nicholas of Tolentine on Fordham Road.

Parkchester was one of several planned apartment communities in New York City built by the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company on the eve of U.S. involvement in World War II. The others are Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village on Manhattan’s East Side, and Riverton Houses in Harlem. When these were built, African-Americans were restricted to Riverton, which was built to much the same standards as the others but was smaller. For a concise history of Parkchester go to https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parkchester,_Bronx

Parkchester is traversed by two wide streets, Metropolitan Avenue and Unionport Road, forming an X and meeting at Metropolitan Oval, a pleasant park. The commercial heart of Parkchester is along Metropolitan Avenue between the oval and the Parkchester subway station. There are numerous restaurants and stores, even a branch of Macy’s. Walking along the length of Metropolitan Avenue, the area had something of the feel of Roosevelt Island, only older, lower-rise, and more spacious. Those of you who are familiar with Roosevelt Island and Parkchester will understand exactly.

Parkchester is well-designed and its population is now very diverse, certainly representative of the crazy quilt that is this city. Although as I started along Metropolitan Avenue the ugliness of East Tremont Avenue was only a block away, the streetscape gave no hint of that. Many building facades are enlivened by terracotta art work; this and the sculptures in the fountain at Metropolitan Oval lend a definite whimsy to the place - but one has to look up and around.

View along Metropolitan Avenue; examples of terracotta artwork.

Top row: fountain and sculpture in Metropolitan Oval. Bottom row: subway station in Hugh J. Grant Circle; marker explaining who Hugh J. Grant was.

This walk ended at the Parkchester subway station, a massive structure with nice tile work in the middle of Hugh J. Grant Circle, named for the youngest-ever mayor of New York. This walk had its share of contrasts and even a few surprises, making for a Sunday afternoon well spent.

All the way around Long Island Sound

START: Atlantic Terminal, Brooklyn (Long Island Rail Road, fully accessible)

FINISH: Moynihan Train Hall, Pennsylvania Station (Amtrak and Long Island Rail Road, fully accessible)

WALKING DISTANCE: 2.7 miles (4.3 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl except where noted. Maps courtesy Google Maps.

This was an all-day adventure on the Long Island Rail Road, Suffolk Transit, Cross Sound Ferry, and Amtrak, plus walks in Greenport, New York and New London, Connecticut. The “walk around town” was a short walk in Greenport and a longer walk in New London. I’m writing about this because the whole trip was accessible. This was a day very well spent and a trip worth doing again.

The first leg of the trip, from Brooklyn to Greenport, was on the original main line of the Long Island Rail Road. The LIRR was chartered in 1834 and started operations from Brooklyn to Jamaica, Queens (9 miles). Today, Jamaica Station is a busy place, the hub of all LIRR branches except one, plus a subway station and one terminal of the JFK AirTrain. I had to change trains at Jamaica and would do so again at Ronkonkoma, the eastern end of electric train service on the main line.

First leg of the trip: Brooklyn to Greenport on the Long Island Rail Road.

At the old Greenport train station.

The LIRR reached Greenport in 1844. The old station building from the 1880s is now a maritime museum, and the ferry to Shelter Island is just steps from the station. Greenport still has something of a fishing village about it but it has been “discovered” by tourists and day trippers.

From the station it’s a short walk along the waterfront and across Front Street to the S92 bus to the ferry at Orient Point. The Suffolk Transit bus was new, comfortable, and accessible. The bus ride takes about 15 minutes, but don’t schedule too close a connection to the ferry as heavy traffic west of Greenport is common and delays the bus. The bus I took ran very late but the ferry for which I had bought a ticket was also late, and was still boarding cars and passengers when I got there.

Second leg of the trip: Suffolk Transit S92 bus.

Scenes from Greenport: map of the walk from the train station to the bus, the waterfront walk, two views on Front Street.

Most of Cross Sound Ferry’s boats are accessible but some are not; mine was not but I got up the stairs to where there was seating. Accessible ferries are noted on their website. Note that the ramp between ferry and dock might be a little steep.

On the crossing there was a good breeze, the sea was choppy, and the day was cool. It felt great to be out on deck!

Ferry route from Orient Point (bottom) to New London, approaching New London, the U.S. Coast Guard training ship Eagle moored near Fort Trumbull, New London from the ferry.

New London has a long history, much of it tied to the sea. New London is home to the U.S. Coast Guard Academy, a U.S. Navy submarine base, and the Navy’s submariners school. Across the Thames River in Groton is a shipyard, still referred to by its old name Electric Boat, that has built submarines for the Navy since before World War I, and Pfizer’s major research and development center. A few miles to the east is Mystic, a major whaling port in the 19th century.

Walking along Bank Street in New London proved quite interesting. There wasn’t much going on this gray Saturday afternoon, but there was history everywhere.

Route of my walk in New London, starting at the ferry and ending at Union Station; historical note outside Thames Landing restaurant; two of several historical plaques in the sidewalk along Bank Street; the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument across from Union Station; where I walked for lunch (it was good but no match for Lenny & Joe’s Fish Tale in Madison, Connecticut).

Before I did that walk I didn’t know that Benedict Arnold set fire to the city in 1781. I certainly didn’t know the city’s connection with the drive to abolish slavery. I was to learn something in front of the old U.S. Customs House, now a museum.

ON THIS SITE, AUGUST 29, 1839 -

“A Federal investigative inquiry indicted 38 enslaved Mende Africans accused of revolt on the high seas and murder of the captain and cook of the Spanish slave ship Amistad which was captured and brought into New London by U.S. revenue cutter Washington, Lt. Gedney commanding.

“This first step to freedom revealed resources which ultimately through trials in Hartford and New Haven and an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court by former President John Quincy Adams, won their liberty as persons to return home by missionary ship to Sierra Leone in 1841.

“Thames River waves lapped against the white-striped low black hull of Amistad for 14 months until it was refurbished and sold for salvage at Joseph Lawrence’s dock. The cargo of silks, satins and other treasures were auctioned off at this Custom House on these front steps.

“Amistad had unjustly held leader Joseph Cinque and his people as slaves in its hold before it became the vehicle for their passage to freedom. Never before, or since, has there been record of such freedom won!”

The Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument was donated to the city by the sons of Joseph Lawrence, a prosperous whaler in the 19th century. Learn more about him and the monument at http://ctmonuments.net/2010/01/soldiers%E2%80%99-and-sailors%E2%80%99-monument-new-london/

Union Station, designed by H.H. Richardson, is a handsome structure completed in 1887. Today it serves Amtrak (Northeast Regional and some Acela trains) and Connecticut Shore Line East trains to New Haven. It was a fine place to await the last leg of this trip, the train to New York.

New London Union Station. Photograph courtesy Wikipedia.

Final leg of the trip, on Amtrak from New London (right) to New York.

George Washington Bridge

Photograph by Edward Steichen, 1931, courtesy MutualArt.

WHERE: The George Washington Bridge, from Manhattan to Fort Lee, New Jersey and back

START/FINISH: 175 Street subway station (A train, fully accessible)

DISTANCE: 3.2 miles (5.1 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl except where noted

I’ve biked across the George Washington Bridge many more times than I’ve driven across it, and the ride back to New York has usually been faster than the car traffic without my even trying. But until today I had never walked across the bridge. So, taking advantage of a beautiful day, I left the state of New York for the first time since February 2020.

The George Washington Bridge, linking upper Manhattan and Fort Lee, New Jersey, opened in October 1931 and is the nation’s busiest bridge. The upper deck (8 lanes) was supplemented by the lower deck (6 lanes) in 1962 and carries Interstate 95 and U.S. Routes 1 and 9. Other highways feed traffic to the bridge at either end. The bike and pedestrian path on the south side of the bridge gets a lot of use, and the approach to it on the New York side is to be rebuilt. A suburban and intercity bus terminal, designed by the great Italian architect Pier Luigi Nervi, is at the Manhattan end of the bridge, elevated over Fort Washington Avenue and Broadway. The bridge is almost as iconic as the Brooklyn Bridge and has been photographed countless times for its mass and beauty.

At the New Jersey side of the bridge is the southern end of Palisades Interstate Park. I had planned to go into the park but the pedestrian entrance at the bridge is being rebuilt as part of a rebuilding of the interchange with the Palisades Interstate Parkway. I’ll just have to go back in a year or so.

Getting to the bridge from either side is easy. Whether biking or walking, crossing the George Washington Bridge is truly rewarding.

George Washington Bridge from Washington Heights, Manhattan, 1988.

Plaque at the elevator at the 175 Street subway station, honoring disability rights advocate Edith Prentiss (1952 - 2021); a small park at the New York end of the bridge with plaques honoring those who perished aboard American Airlines flight 587 in November 2001, and local activist Louie Stern; memorial at the New Jersey end of the bridge to Port Authority Police Officer Bruce Reynolds, who died on September 11, 2001.

View looking south from the bridge; the New Jersey tower; obligatory selfie.

The Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway, Part 1

Route of today’s walk, courtesy Google Maps.

WHERE: The Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway

START: Broadway and Bedford Avenue (B62 bus)

FINISH: Flushing Avenue and Clermont Avenue (B69 bus)

DISTANCE: 1.9 miles (3.1 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl.

Brooklyn’s waterfront along the East River and Upper New York Bay was, until fairly recent times, given over to docks and industry. As such, very little of it was accessible to the general public. This remained the case even after the docks and waterfront became largely quiet.. In 1966 the U.S. Navy closed the Brooklyn Navy Yard, where many warships were built, including the battleships Arizona and Missouri, idling many thousands of shipyard workers. Environmental advocate Milton Puryear had a vision to make the waterfront accessible to the communities abutting it. In 2003 he and two other activists, Brian McCormick and Meg Fellerath, founded the Brooklyn Greenway Initiative (BGI) to connect the waterfront to the communities along it and to create a 14-mile bicycle and pedestrian path linking these communities, from Greenpoint in the north of Brooklyn to Bay Ridge, just north of the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge. In 2021 a significant amount of the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway is complete in either final or interim form, and it has become a major resource for transportation and recreation. BGI has expanded the scope of the Greenway to continue along the Narrows, through Coney Island, along Jamaica Bay almost to JFK Airport, and across Jamaica Bay to the Rockaway Peninsula, a total of more than 30 miles. Learn more about this outstanding organization and the Greenway at https://www.brooklyngreenway.org/.

I was a member of BGI’s Board of Directors from 2008 - 2021 and the Board Chair from 2013 - 2019, and saw the waterfront evolve with new residential development and park land, the Brooklyn Navy Yard re-imagined as a cluster of high-tech and artisanal industry (and yes, ship repair), Brooklyn Bridge Park coming into being where docks used to be south of the Brooklyn Bridge, Industry City and neighboring Bush Terminal following a similar path as the Brooklyn Navy Yard, and communities up and down the waterfront finally being able to enjoy it. As a cyclist I’ve biked the entire 30-plus-mile Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway many times; now, since the stroke, I am walking the Greenway with the goal of covering its entire length on foot to get a sense of a pedestrian’s experience of the Greenway and its accessibility.

Today I did my third Greenway walk, even though this is the first time I’m writing about it on this site. To recap the previous two walks: the first started in Long Island City, Queens, and along the northern part of the Greenway in the Brooklyn neighborhoods of Greenpoint and Williamsburg. The second walk was a shorter walk wholly within Williamsburg.

Maps of the first and second Greenway walks, courtesy Google Maps.

Some views from the first two Greenway walks: two views of the Greenway on West Street in Greenpoint (bike lane is painted green), crossfit gym on Franklin Street, Brooklyn Greenway roundel with unofficial smiley face (I like it) on Kent Avenue in Williamsburg, two views of the Williamsburg Bridge.

On today’s walk I picked up where I left off on the second walk. Twenty years ago, the westernmost blocks of Broadway were run down with few people around except for those going to the landmark Peter Luger’s Steak House. Now, the same blocks have cafes, bars, new residential buildings, and Peter Luger’s. Twenty years ago, Kent Avenue, running parallel to the waterfront, had a lot of truck traffic on weekdays but was deserted on weekends, making for easy bike riding. Hardly anyone lived on Kent Avenue. Today, nearly all the new waterfront development is centered on Kent Avenue. For an excellent look at what Kent Avenue was, and was becoming early in its redevelopment, go to https://forgotten-ny.com/2009/01/i-kent-explain-a-brooklyn-waterfront-avenue/.

Clockwise from upper left: Broadway, looking east from near Kent Avenue; view from the foot of Division Avenue (this could become a small park!); two views of the Greenway along Kent Avenue, with the Brooklyn Navy Yard at right.

Proposed car-free zone on Kent Avenue. Map courtesy Google Maps.

North of Division Avenue, Kent Avenue is much narrower than it is to the south. The sidewalks are narrow and there’s a very busy two-way bike path on the west side of the street,. There isn’t enough room for pedestrians, cyclists, cars, trucks, and city buses. I would like to see Kent Avenue closed to motor vehicles except emergency vehicles and small delivery trucks, year round, from Broadway to Bushwick Inlet Park (solid blue line on map). Making this street a full-time pedestrian mall, similar to Rue Ste-Catherine in Montréal, would create a safer, more accessible situation for pedestrians and cyclists. It could become a second showpiece for the Greenway; I’ll discuss the first shortly.

Between Division Avenue and the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway (Interstate 278), Kent Avenue is wide enough to accommodate two travel lanes, left-turn lanes, car parking, and a wide bike path that is separated from a wide sidewalk by native plantings. Disused marine containers stacked three high form an unexpectedly attractive wall that pays homage to the Brooklyn Navy Yard on the other side.

Running parallel to the expressway is Williamsburgh Street West, where the Greenway consists of a sidewalk and a bike lane separated from car traffic by concrete “Jersey barriers.” A short distance along is a real gem, the Naval Cemetery Landscape.

From the 1830s until World War II a naval hospital occupied the southeast corner of the Brooklyn Navy Yard. When the hospital was moved to Queens many of the remains in the hospital cemetery were disinterred and moved elsewhere. Some remains were thought still to be there decades later. BGI obtained an agreement with the Brooklyn Navy Yard Development Corporation to transform the former cemetery site into a contemplative space and secured funding from a private foundation for this. The Naval Cemetery Landscape is stunning, a peaceful oasis, a fitting memorial to those who served in the Navy and died in the hospital. It has also become a green space for a diverse community that sorely lacks green space. I have often said that the Naval Cemetery Landscape is the best part of the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway, making the Greenway more than just a ribbon of asphalt. The site is filled with native, non-invasive plants that BGI co-founder Milton Puryear championed. Read more about the history and design of the Naval Cemetery Landscape at https://www.brooklyngreenway.org/naval-cemetery-landscape/history-and-design/.

Some views of the Naval Cemetery Landscape.

Back to the Lower Bronx River

WHERE: Park trails and local streets along or near the lower Bronx River

START: Soundview Ferry Terminal (fully accessible)

FINISH: Simpson Street subway station (2 and 5 trains; fully accessible)

DISTANCE: 3.9 miles (6.3 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl

The NYC Ferry has received some criticism as a rather heavily subsidized boat ride for tourists. There is some truth to that but it also provides fast and cheap transportation to and from some otherwise hard-to-get-to parts of the City. New York City’s waterways constitute an underutilized path for public transportation.

Having discovered that I could take NYC Ferry from the foot of Wall Street in Manhattan to Soundview in the Bronx, a 50-minute ride for $2.75, I put together a good walk combining some unexplored territory for me, and a route I’ve biked and/or walked. From the time I left the subway at Wall Street, to the time I stepped off the train at Grand Army Plaza going home, the whole trip was accessible.

Route of today’s walk, courtesy Google Maps.

Profile of today’s walk, courtesy Google Maps.

The ferry from Wall Street to Soundview gives a good look at different parts of the City.. Not well known but very interesting is North Brother Island (lower left corner on the map); the ferry passed between it and privately owned South Brother Island. From the ferry one can see the ruins of Riverside Hospital on North Brother Island. This was a City hospital for the chronically ill, and its most famous resident was “Typhoid Mary” Mallon.

The Soundview ferry terminal is at Clasons Point, across the East River from College Point, Queens (see my post “On the Trail of Conrad Poppenhusen” under “The Stair Streets of New York City”), just west of the Bronx-Whitestone Bridge, and just across the Bronx River from the Hunts Point Terminal Market, from which most of the City’s perishable foods are distributed. Clasons Point Park is a little riverfront park at the ferry terminal, with sweeping views. Soundview Avenue runs northwest from Clasons Point Park, and after a short distance the Shorehaven waterfront path begins.

Left to right: selfie at Clasons Point Park, just off the ferry, with the Bronx-Whitestone Bridge in the background; view from the Shorehaven Esplanade with the towers of Manhattan in the distance; bungalows along Leland Avenue.

At the end of the Shorehaven Esplanade I continued on Bronx River Avenue and then Leland Avenue, into one of those parts of thew Bronx where I almost had to slap myself and ask, “Am I in the Bronx?” This is a community I’ve biked through a few times on the NYC Century and the Tour de Bronx. It is a community near the water, mostly of small bungalows nestled close to each other. It is not at all the Bronx that is often portrayed in the media and it is not the only such community in the Bronx. The Country Club neighborhood, Riverdale, and the brownstones on Alexander Avenue in the South Bronx, all have left me astonished, and not just the first time I have seen them. Flags of the United States and Puerto Rico were flying in about equal number from in front of people’s homes.

At O’Brien and Leland Avenues I started out on the bike and pedestrian trail through Sound View Park. This park hugs the mouth of the Bronx River. Along most of the trail it seemed that I was in a dandelion snowstorm. Like most of the City’s parks that operate without a not-for-profit conservancy, Sound View Park needs some attention, but it is generally in good condition and it proved to be a quiet oasis.

Left to right: First row, path in Sound View Park with a lot of dandelion seeds, and NYC Greenway roundel. Second row, two sides of the same sign at the north entrance to the Sound View Park trail (Colgate and Lafayette Avenues.)

Along the north end of the Sound View Park trail are several baseball fields, all of which saw a lot of use today. Beyond the north end of the trail are a few blocks of high-rise apartment houses and assorted light industry, before returning to the Bronx River and entering Concrete Plant Park. I wrote about this park in my 2020 post entitled “Lower Bronx River Greenway,” so I won’t repeat it here but please refer back to it. Suffice it to say that it is an urban gem and the revival of the Bronx River as a home for fish and birds is testimony to the great work of the Bronx River Alliance.