High Kingsbridge and Low Kingsbridge

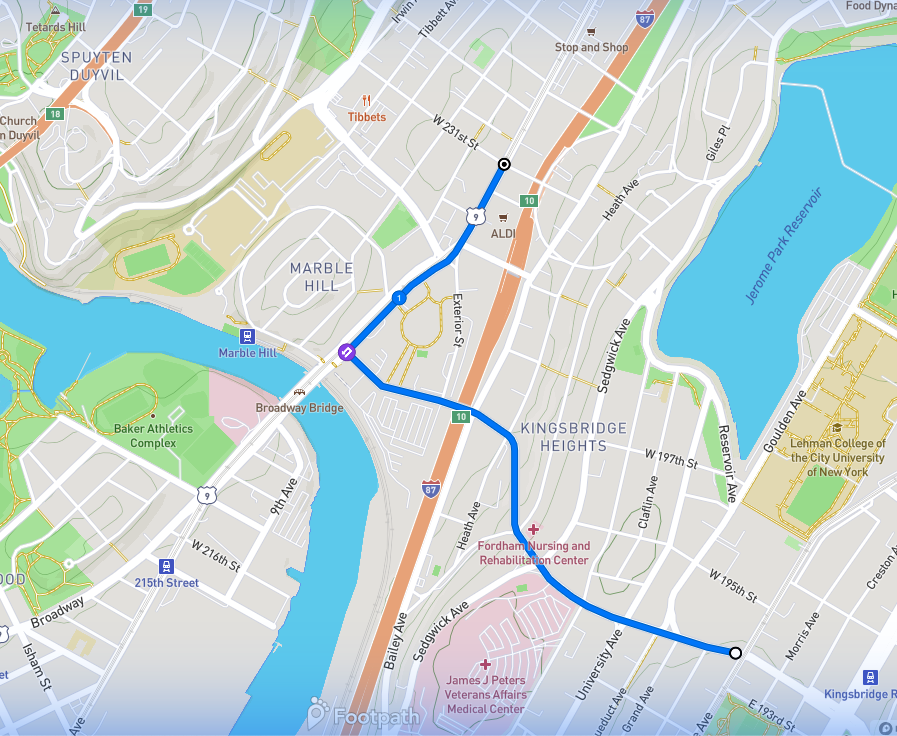

Map of this walk, reading from bottom to top.

WHERE: The Kingsbridge section of the Bronx

START: Kingsbridge Road subway station (4 train)

FINISH: 231 Street subway station (1 train), fully accessible

DISTANCE: 1.28 miles (2.06 kilometers)

Photographic credits as noted. Map courtesy footpathmap.com.

This day’s walk was supposed to have been longer, taking in a lot of pre-World War II architecture on the upper Grand Concourse before ending up in Kingsbridge. My friend Joe was the only person who joined me, so we did a different walk. What this walk lacked in distance was offset by physical challenge. Walking downhill is harder by far than walking down stairs. This walk featured a long, steep downhill on West Kingsbridge Road.

We started at the massive Kingsbridge Armory, possibly the largest armory ever built. It was constructed between 1912 and 1917 and covers all of a 5-acre (2 hectare) site. It was designated a city landmark in 1974. At that time the city's Landmarks Preservation Commission called it "an outstanding example of military architecture." The building fell into disrepair and title to it was transferred to New York City in 1996. Before that time and since, there have been several plans for re-use of the armory, none of which have come to fruition as the City and the community have been unable to develop a common vision for the armory. Meanwhile, it stands mute and unused. Outside the armory along West Kingsbridge Road were people selling all manner of stuff. Laid out on a blanket was an assortment of women’s wigs. I wish I had photographed all this. I might have to go back soon.

Kingsbridge Armory, looking west along West Kingsbridge Road from the elevated subway station. Photograph courtesy curbed.com.

We continued west on a gentle uphill past University Avenue and the Old Croton Aqueduct crossing, before beginning a tough downhill to the Major Deegan Expressway (Interstate 87) starting at Webb Avenue (for which the Webb Institute of Naval Architecture was named) and the Bronx Veterans Affairs Medical Center. This descent was 138 feet (42 meters) in 0.39 mile (0.63 kilometer), or 6.7 percent. Some sense of this can be gained from the following screenshots from Google Earth, proceeding west.

The rest of the walk was unremarkable, going past a large shopping center across from which is a large public housing complex. These were built on the bed of the old Spuyten Duyvil Creek. For more about this area go to my post “Over Hill and Through Riverdale” on the page “The Stair Streets of New York City.”

For me to walk down a steep hill requires care and mindfulness. Looking down the hill from Sedgwick Avenue, I said to Joe, “I’m not liking this hill.” I was concerned by the steepness of the hill and uncertain about the condition of the sidewalk. But I wasn’t going to go back to the Kingsbridge Armory, so we pressed on, carefully and successfully. I felt a lot of satisfaction after this walk.

A Basketball Court and a Ghost Railway

WHERE: New Rochelle and Pelham, New York

START: New Rochelle station (Metro North Railroad, New Haven Line, and Amtrak), fully accessible

FINISH: Pelham station (Metro North Railroad, New Haven Line), accessible at the eastbound (outbound) platform

DISTANCE: 2.0 miles (3.2 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl except as noted. Map courtesy footpathmap.com

Route of this walk, reading from right to left.

I’ve recently met an abstract artist, Scott Albrecht, whose work I like a lot. Scott is also a very kind and intelligent soul. He designed the surface of a basketball court in a city park in New Rochelle, just north of New York City. I was determined to have a look for myself and combined that with a visit to one of the few remaining vestiges of the New York, Westchester and Boston Railway north of the Bronx. The route was fairly hilly, making for a decent workout on a crisp late November day.

The walk started at the New Rochelle station of Metro North and Amtrak. From the station house at the westbound (inbound) platform I walked up the ramp to North Avenue and turned left. There was a fully accessible detour around where North Avenue crosses the New England Thruway (Interstate 95) owing to the rebuilding of the North Avenue crossing. I continued a few blocks up North Avenue, through a tired-looking commercial strip, then crossed and turned left on Lincoln Avenue. A few blocks on, I crossed Malcolm X Way then crossed to the opposite (south) side of Lincoln Avenue and turned right. At this point Lincoln Avenue is on a steep-but-not-too-steep hill, and on the left was my first stop, Lincoln Park.

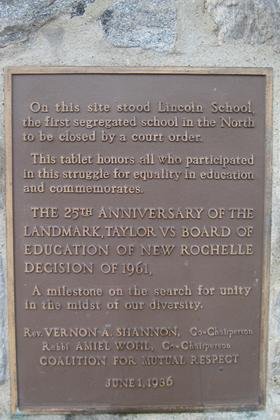

Lincoln Park is on the site of Lincoln School, a segregated public school that was closed by court order in 1961 and subsequently razed. This history is memorialized on a plaque on Lincoln Avenue near the corner of Prince Street.

Just inside the park was the basketball court I was looking for. This was completed in 2018 in partnership with Project Backboard and the National Basketball Players Association. Seeing an aerial view, I had to see it at ground level. I was not disappointed.

Image courtesy Google Earth. Lincoln Avenue is at the bottom.

For all the life and activity there is on a basketball court, it can be a pretty humdrum place, just a rectangle of asphalt. The Lincoln Park court is something special, a gift to a diverse community that might have been overlooked. Perhaps this can be viewed as a mural put not on a wall but on an athletic surface. Scott Albrecht’s horizontal mural fills its space differently than the usual vertical mural would, leading to a different interaction. The patterns on the court could be seen as mimicking how a player maneuvers in a basketball game. It is not representational art. It’s not what’s there; it is what we see. This place allows one to see and imagine many things while shooting hoops or, as I did, just looking on. I’m glad I came here, for it is a special place.

Leaving the park, I continued uphill (west) on Lincoln Avenue through a tidy neighborhood. The sidewalks were in good condition and most of the curb cuts were. At the boundary between the City of New Rochelle and the Village of Pelham (pronounced pell-um) I saw this.

A short distance on I turned left onto Highbrook Avenue, stumbling but not falling as I did so. Suffice it to say that the sidewalks in leafy Pelham could benefit from some attention. Ahead of me was the Highbrook viaduct, built by the New York, Westchester and Boston Railway.

I’ve written about the “Westchester” after several previous walks in the Bronx. This state-of-the-art (for 1912) commuter railroad was a spectacular failure, built by the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad and essentially competing with the New Haven. After service on the “Westchester” ended on the last day of 1937, little effort was spared to eradicate it from the landscape, especially in Westchester County. It seems strange, then, that this substantial structure was left standing. Just west of here was the railroad’s Mount Vernon Junction, from which two tracks went north to White Plains and two went east to New Rochelle (later to Port Chester). The Highbrook viaduct is on what was the Port Chester branch. Part of the right-of-way east and west of the viaduct is now preserved as a park. Just past the viaduct is this historical marker.

Just past this marker I turned onto Harmon Avenue in the direction of the Pelham station. Harmon Avenue has many fine old houses, one of which, number 65, really caught my eye.

Lunch was at a nice neighborhood restaurant across from the Pelham station called The Rail House.

This was a good, enjoyable walk with the benefit of public art along the way. Thanks to Scott Albrecht for creating the work that got me up there. There is so much to see if we just open our eyes and minds.

Back to the George Washington Bridge

WHERE: The north walk on the George Washington Bridge, from New York to New Jersey and back

START/FINISH: 175 Street subway station (A train), fully accessible; also several Bronx bus lines and the M4 bus

DISTANCE: 3.3 miles

Photographs by Michael Cairl except as noted. Map courtesy footpathapp.com.

Map of this route.

In 2021 I posted “The George Washington Bridge” about a walk I took over this bridge, from Manhattan to New Jersey and back. Earlier this year the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey re-opened the footpath on the north side of the bridge after years of improvements, including making it fully accessible. The Port Authority is now rebuilding the footpath on the south side, on which I did the 2021 walk. I took advantage of an unseasonably warm October Saturday to walk the new footpath and, incidentally, mark the 92nd anniversary of the opening of the bridge.

This walk started a few blocks from the bridge, at West 177 Street and Fort Washington Avenue, taking the elevator from the 175 Street subway station. One block north is the George Washington Bridge Bus Station, the terminal for many local New Jersey and New York bus routes and some longer-distance buses. This opened in 1963 and is a rare structure in the United States designed by Pier Luigi Nervi (1891 - 1979), an Italian structural engineer who was noted for the innovative use of reinforced concrete in construction. For more information about this engineering genius go to https://pierluiginervi.org/.

George Washington Bridge bus terminal. Image courtesy nycrc.com.

The entrance to the north footpath is at West 180 Street and Cabrini Boulevard, five short blocks from the subway elevator. Flanking the entrance is some seating to the south, which was most welcome at the end of the walk, and some tables and seats to the north.

Up the ramp and before the bridge is an area with an historical panorama of the bridge. It’s interesting and well done.

Once the south walk of the bridge is reopened, it will be primarily a bicycle path. In the meantime both bicycles and pedestrians share the north walk, which is wide enough to accommodate both groups comfortably. That is a good thing; on this day, while there was a good amount of foot traffic, there were a lot of cyclists. I was once one of them.

At mid-span the state line is clearly marked.

The day offered some spectacular views.

View from the New York side of the bridge, Barely visible in the distance is the new Tappan Zee Bridge, officially the Mario Cuomo Bridge, 17 miles away.

View from the New Jersey side of the bridge.

Just past the New Jersey end of the bridge is a serpentine ramp leading to Hudson Terrace in Fort Lee, and a set of 42 stairs for those wishing a shorter trip. Before the reconstruction of the north walk there was a footbridge over the ramp to the Palisades Interstate Parkway, with stairs on either side (to the bridge and to Hudson Terrace) and a metal channel bolted to the stairs so one could roll a bicycle up and down. The new stairs do not have or need this. There is another set of 10 stairs going up into Palisades Interstate Park. I went up into the park and walked a short distance along the Long Path. I had to walk very carefully to avoid tree roots and stones and the occasional muddy area. But this walk was rewarded by some nice views of the bridge.

Coming back to Manhattan I took advantage of the seating area and chatted with some cyclists who had seen me walking as they rode to New Jersey and back. One of them, Marcos, ended up being the interpreter as they were all Spanish-speaking. I keep running into kind and interesting people on these walks. I am blessed.

Kudos to the Port Authority for doing such a great job rebuilding the north walk! It was a pleasure to walk this. Maybe add some seating in the large open areas they added by the two towers.

And just throwing this in: a picture I took of the George Washington Bridge in 1988, from just south of Fort Tryon Park. Pure luck: right place, right time. 50 mm lens on a Canon AE-1, Kodachrome 64 film.

Eastern Parkway (Brooklyn)

WHERE: Eastern Parkway and a detour into the northern part of Crown Heights, Brooklyn

START: Eastern Parkway - Brooklyn Museum subway station (2, 3 trains), fully accessible

FINISH: Crown Heights - Utica Avenue subway station (3, 4 trains), fully accessible

DISTANCE: 2.54 miles (4.09 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl except as noted. Map courtesy gmap-pedometer.com.

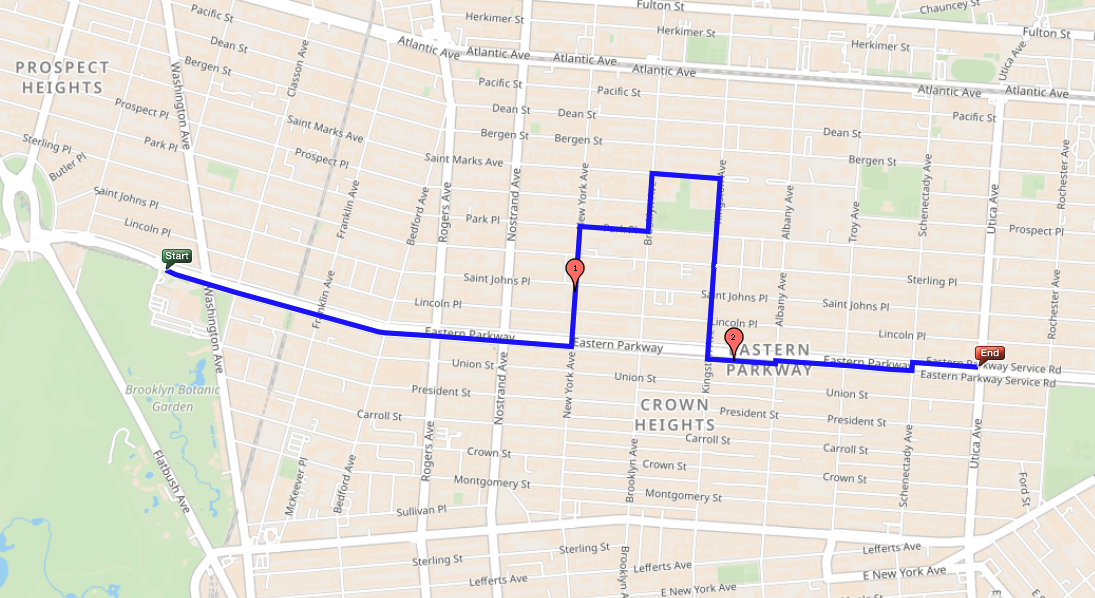

Route of this walk, reading from left to right.

New York City has many streets called “Parkway” but only a few are broad, landscaped avenues, typically with a main road in the middle, landscaped malls on either side, and side roads.

Eastern Parkway, looking east from Rogers Avenue.

In the Bronx, Pelham Parkway, Mosholu Parkway, and Mount Eden Parkway fit this description. In Brooklyn there are Ocean Parkway, going south from Prospect Park, and Eastern Parkway, going east from Grand Army Plaza. These were planned and built in the late 19th century as part of an ambitious plan of civic improvements by the City of Brooklyn. Today’s walk connected two accessible subway stations on Eastern Parkway, starting at the Brooklyn Museum, on a cloudless Sunday.

When the Eastern Parkway - Brooklyn Museum subway station was rehabilitated, architectural artifacts from the Museum’s collection were put in the station mezzanine. It’s a nice collection. Here are two examples:

I’ve often said that if New York didn’t have the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Brooklyn Museum would be the City’s pre-eminent art museum. The present building, while large, is only about one-fourth its originally intended size.

The Brooklyn Museum as conceived in the 1890s. Only the front part and some of the interior were built. Image courtesy archimaps.tumblr.com.

The Brooklyn Museum has long had a renowned collection of ancient Egyptian art. My late father told me how much he enjoyed going to the Brooklyn Museum as a youngster to see its Egyptian collection. It has important holdings in other periods of art. In the mid-2000s the Brooklyn Museum added a modern front entrance. People either love it or hate it. I love it for providing a much better entryway to the museum and for its sitting stairs, oriented not straight ahead to Eastern Parkway but toward Washington Avenue just to the east, and to the rest of Brooklyn. This physical orientation coincides with the Brooklyn Museum doing a better job of embracing Brooklyn’s artists and being more a part of where it is. To me, the YO/OY sculpture out front encapsulates perfectly this sense of place, of the spirit of Brooklyn. It says something different depending on how one sees it.

From the Museum, walk east on Eastern Parkway on the pedestrian (narrower) side of the bike-pedestrian path. Along the pedestrian paths on either side of the main road are plaques honoring local men who died in battle in World War I. Here’s an example near Washington Avenue in honor of Private George A. Greb.

At Bedford Avenue look just to the right at the huge Bedford Union Armory, now called The Major R. Owens Health and Wellness Community Center, named after the late Congressman Major Owens. Opened in 1903, the former Bedford Union Armory served as a dirt-floored training facility and stable for the Army National Guard’s horseback units. After sitting abandoned for decades, redevelopment began in 2015 with the goal of creating valuable community space while preserving as much of the building’s irreplaceable, century-old architecture as possible.

Bedford Union Armory. Image courtesy curbed.com.

Continuing on Eastern Parkway, near the intersection of Nostrand Avenue is the former Loew’s Kameo theater, built in the mid-1920s, now a church. Note the terra cotta ornamentation.

On the opposite side of Eastern Parkway is the former Kings County Savings Bank, now Banco Popular, a sort-of-Art Deco structure from 1930. Quite a grand structure for a neighborhood bank branch, albeit at a major intersection.

At New York Avenue, one block east of Nostrand, the route crosses Eastern Parkway to go north. There are some fine old row houses on New York Avenue.

Many of the avenues intersecting Eastern Parkway are named for cities in New York State: New York, Brooklyn (a separate city until 1898), Kingston, Albany, Troy, Schenectady, Utica, Rochester, and Buffalo. Somehow, Syracuse was overlooked.

At the corner of New York Avenue and Park Place is an imposing structure that, despite its appearance, is not an orphanage. It is the former Brooklyn Methodist Episcopal Home for the Aged and Infirm, built in 1889 as housing for elderly members of Methodist congregations. In 1976 the Methodist Home moved to a new facility in the East New York section of Brooklyn that it still occupies. The old facility lay derelict for decades until it was acquired by the Hebron French-Speaking Seventh Day Adventist School. Much of the complex remains in disrepair, a sad outcome for this gloomy yet stunning place.

Turning right onto Park Place, walk on the side opposite the Methodist Home, as the sidewalk is in better condition. Turn left onto Brooklyn Avenue. On the opposite side is Brower Park, and in the park between Prospect Place and St. Marks Avenue is the Brooklyn Children’s Museum, the oldest children’s museum in the world (1899).

Brooklyn Children’s Museum extension (opened 2006, Rafael Viñoly Architects).

Turn right onto St. Marks Avenue and then right onto Kingston Avenue, continuing the circuit of Brower Park. At the corner of Park Place is the magnificent Historic First Church of God in Christ. The congregation purchased this property in 1939 and transformed it from a bus garage.

Continue to and cross Eastern Parkway, then turn left onto Eastern Parkway. At the southwest corner is 770 Eastern Parkway, the headquarters of the Lubavitcher Chasidic community. Across Kingston Avenue is the Jewish Children’s Museum (opened 2004, architects Gwathmey Siegel) with its outsized dreidel in front.

In front of 770 Eastern Parkway.

Jewish Children’s Museum.

Walk east on Eastern Parkway on the pedestrian (right) side of the pedestrian/bike path; it’s in better condition than the sidewalk. Continue three blocks to Schenectady Avenue, cross and turn right on Eastern Parkway. Finish the walk at the elevator to the subway station at Utica Avenue, across from which is St. Matthew Roman Catholic Church. Two other Catholic parishes, St. Gregory the Great and Our Lady of Charity, worship here.

Eastern Parkway offers a beautiful walk and much to look at along the way. It is an elegant boulevard through an ever more diverse community. The detour north of Eastern Parkway was rewarding for a look at buildings both magnificent and unexpected.

Lower Manhattan Old and New

WHERE: Battery Park, Battery Park City, World Trade Center

START: Bowling Green subway station (4, 5 trains), fully accessible

FINISH: Fulton Transit Center (2, 3, 4, 5, A, C, J trains), fully accessible

DISTANCE: 1.9 miles (3 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl except as noted. Map courtesy gmap-pedometer.com.

Map of this route.

Much of Lower Manhattan is built on landfill, the shoreline having been extended over the centuries. Water Street was once at the East River shoreline. This walk took in Battery Park, some of which is on fill, and Battery Park City, all of which is, before going past the World Trade Center.

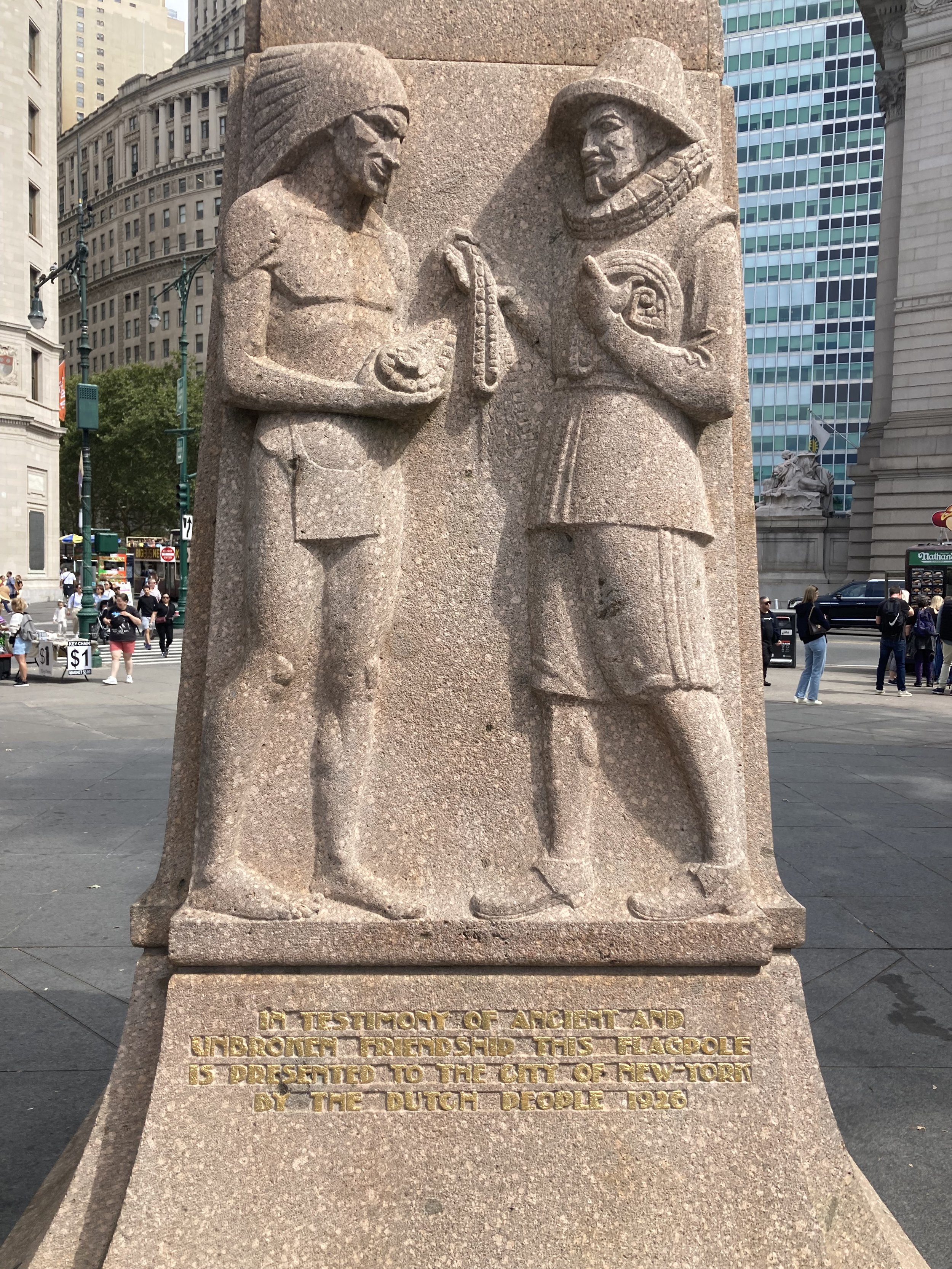

This walk began at the Bowling Green subway station, in front of the old U.S. Customs House that now is home to the Heye Foundation - Museum of the American Indian (a unit of the Smithsonian Institution), and the U.S. Bankruptcy Court. Cross State Street and bear slightly to the left to see the Netherlands Monument, donated by the Netherlands in 1626 on the three-hundredth anniversary of the founding of New Amsterdam.

From the Netherlands Monument walk back toward State Street and turn right. Directly ahead is the original (and still in use) entrance to the Bowling Green subway station, which opened in 1905. This is similar to other street-level control houses built for the first subway.

Continue walking along State Street, alongside Battery Park. At Bridge Street there is a memorial to John Ericsson (1803 - 1889), naval architect, engineer, and builder of the U.S.S. Monitor that fought in the Battle of Hampton Roads in 1862.

John Ericsson holding a model of U.S.S. Monitor.

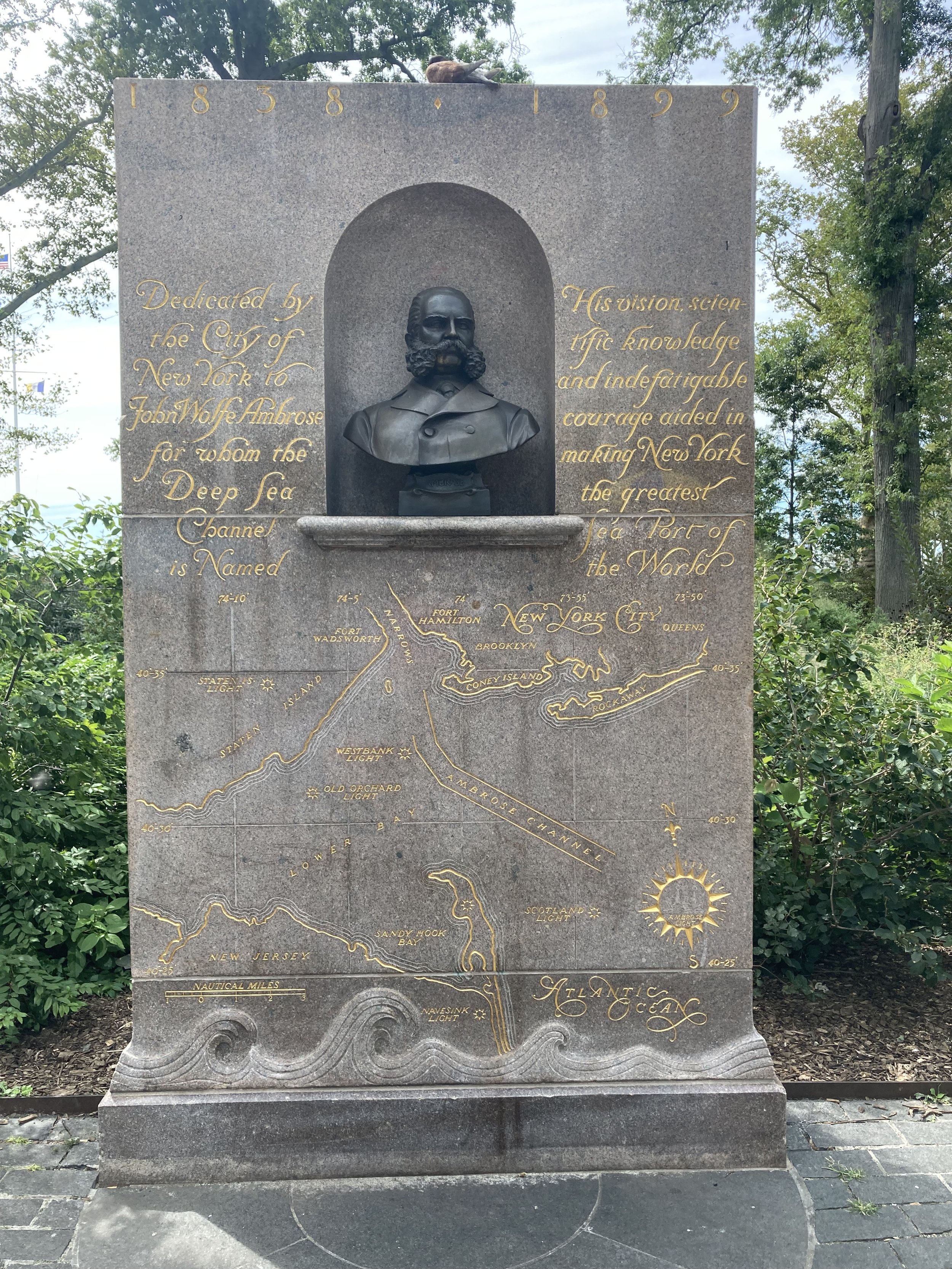

Continue walking. At Pearl Street is a memorial to John Ambrose (1838 - 1899), whose vision and persistence resulted in the deep sea channel to New York Harbor, which improved the visibility of the Port of New York, making New York City the heart of commerce in the United States. This channel is named in his honor, as was the Ambrose lightship off Sandy Hook, at the entrance to the harbor. More about Ambrose can be found at https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=145669.

Just past the Ambrose monument, turn right into the park, passing a playground on the left and a carousel on the right. Passing a restaurant on the left, turn right onto the park path. Ahead is the World War II East Coast Memorial. From the Memorial’s website:

The World War II East Coast Memorial is located in Battery Park, New York City. This memorial commemorates those soldiers, sailors, Marines, coast guardsmen, merchant mariners and airmen who met their deaths in the service of their country in the western waters of the Atlantic Ocean during World War II. Its axis is oriented on the Statue of Liberty. On each side of the axis are four gray granite pylons upon which are inscribed the name, rank, organization, and state of each of the over 4,600 missing in the waters of the Atlantic. For names where an individual’s remains have subsequently been accounted for by the U.S. Department of Defense, a rosette is placed next to the name on the memorial to indicate that the person now rests in a known gravesite.

Photograph courtesy American Battle Monuments Commission

Continuing on past the World War II East Coast Memorial, we come to a monument to Admiral George Dewey, commander of U.S. naval forces that defeated the Spanish at the Battle of Manila Bay in 1898.

Next is the Castle Clinton National Monument. This was built on an artificial island in 1812 as part of a network of defenses of New York Harbor, others being Fort Wadsworth on Staten Island and Fort Lafayette in Brooklyn, the latter having been demolished to make way for the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge. Fort Clinton was was never used for warfare and its cannons never fired a shot. In 1824, the New York City government converted Fort Clinton into a 6,000-seat entertainment venue known as Castle Garden, which operated until 1855. A popular Swedish opera singer of the 1850s, Jenny Lind (“the Swedish Nightingale”), performed here. Castle Garden then served as an immigrant processing depot for 35 years. When the processing facilities were moved to Ellis Island in 1892, Castle Garden was converted into the first home of the New York Aquarium, which opened in 1896 and continued operating until 1941. The Aquarium re-opened in Coney Island, Brooklyn in 1957.

Walk around Castle Clinton on the seaward side, then turn to the left on the path going back toward the water. To the left is New York’s Korean War Memorial.

Take the ramp down toward the promenade. On the left is City Pier A. It was built from 1884 to 1886 as the headquarters of the It was built from 1884 to 1886 as the headquarters of the New York City Board of Dock Commissioners (also known as the Docks Department) and the New York City Police Department's Harbor Department. Pier A, the only remaining masonry pier in New York City, contains a two- and three-story structure with a clock tower facing the Hudson River. The pier is a New York City designated landmark and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Until 1992 it was a fireboat station and was later redeveloped as a restaurant and events venue.

Cross Battery Place and turn left, passing the Museum of Jewish Heritage across the street. Continue to 2 Place and turn left, walking toward the river. Walk up to a 2-piece sculpture of African musical instruments and turn right. At 3 Place, turn left onto the Battery Park Esplanade, staying on it as it turns right to parallel the river.

Battery Park City, where we are now, is built on a large landfill where there used to be piers on an active waterfront. With the rise of containerized shipping after World War II, most of the port’s cargo traffic moved to New Jersey, leaving once-busy piers and adjoining areas derelict. The start of construction of the World Trade Center in the late 1960s provided the impetus to do something with the rotting piers. They were removed and the shoreline was expanded westward. The first apartment buildings arrived in Battery Park City in the late 1970s.

Continue on the promenade to where it turns right at the marina. On your right is the New York City Police Memorial. The names of police officers who died in the line of duty are inscribed on the wall.

Make your way to and into the glass atrium called the Winter Garden. It opened in 1988 as a public space that also hosts concerts and art exhibits. It was heavily damaged in the attack on September 11, 2001 and was rebuilt. The twelve live palm trees are a notable feature of the Winter Garden.

Walk past the grand staircase and exit the building, then proceed to the crossing of West Street to the left and cross here. Once across West Street, cross Fulton Street and turn left. One World Trade Center is on the left. On the right is the North Tower Pool, part of the 9/11 Memorial. This occupies the footprint of the north tower of the World Trade Center that was destroyed in 2001. Names of people who died in the attack are inscribed on the parapet surrounding the pool. Linger around the memorial or continue along Fulton Street past Greenwich Street (restored with the reconstruction of the World Trade Center site) and Church Street. Continuing along Fulton Street, St. Paul’s Chapel (1770) and churchyard are on the left. Cross Broadway and finish the walk at the Fulton Transit Center.

There is so much history on this walk, and outstanding views of the harbor. Most of the walk is off city streets. I did this walk on a very pleasant day. Pick a nice day and do it yourself.

Manhattan Bridge, and then some

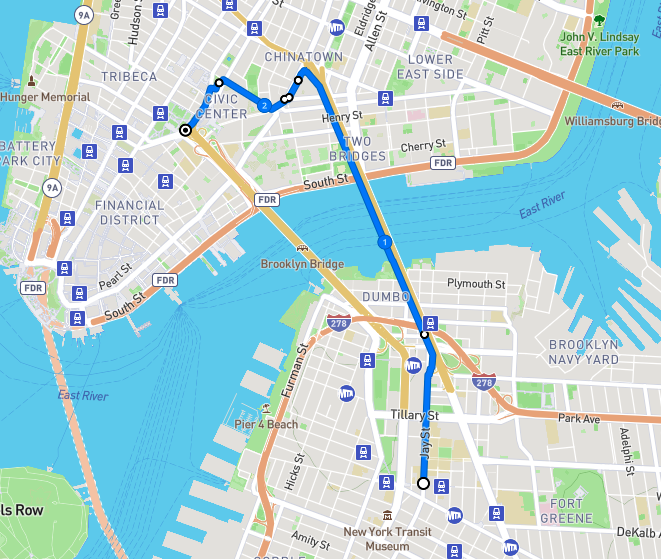

Route of this walk, reading from bottom to top. Map courtesy footpathmap.com.

WHERE: To, across, and from the Manhattan Bridge, going from Brooklyn to Manhattan.

START: Jay Street - Metrotech subway station (A, C, F, R trains), fully accessible

FINISH: Brooklyn Bridge - City Hall subway station (4, 5, 6 trains), fully accessible and connected to the Chambers Street subway station (J train), also fully accessible

DISTANCE: 2.45 miles (3.94 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl except as noted.

After falling and breaking my wrist five weeks ago, which resulted in surgery, I must admit I was feeling a bit gun-shy about going on walks. But I have been commuting to work normally, and I did a walk in upper Manhattan two Saturdays ago. On a picture-perfect day in New York, it was time for a longer walk, being mindful about each step. It’s possible to be mindful and still enjoy the walk. I’ve biked across the Manhattan Bridge many times and have taken the subway across the bridge many more times than that, but until today I had never walked across the bridge. This turned out to be a thoroughly enjoyable walk.

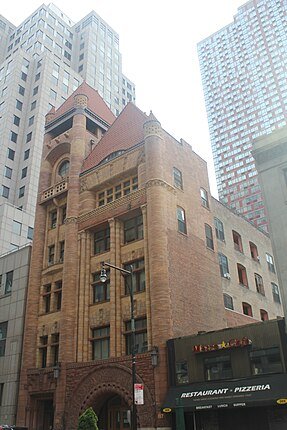

The walk began in Downtown Brooklyn at the Jay Street - Metrotech subway station. Metrotech is an office complex built mostly in the 1980s to replace blocks of buildings that were well past their prime. Metrotech also includes New York University’s engineering school, previously Polytechnic University and before that the Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn. Metrotech is architecturally boring but walking north on Jay Street, just before Metrotech, is a gem: the old Brooklyn Fire Headquarters (1892), designed by the great Frank Freeman (1861 - 1949), a prolific Brooklyn-based architect.

Old Brooklyn Fire Headquarters. Photo courtesy Epicgenius.

Continue north on Jay Street past Metrotech. The area to the left (west) is the Brooklyn Civic Center, home to state and federal court houses and many government offices. Before World War II this area was criss-crossed by elevated train lines going from the Brooklyn Bridge to points south and east in Brooklyn.

Cross busy Tillary Street and continue on Jay Street. Cross only on a complete traffic signal interval; do not attempt to cross once the signal has already turned green. On the right, past Tillary Street, is St. James Cathedral of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn. This is by no means the largest Catholic church in Brooklyn but it is the oldest. Pope Paul VI stopped by in 1965 and Pope John Paul II did so in 1979.

St. James Cathedral.

A bit farther north is the entrance to the Manhattan Bridge walkway, the beginning of which is a pleasant plaza.

Entrance to Manhattan Bridge footpath.

Photo of me taken in exchange for a photo I took of three women who had just walked across the bridge.

The Manhattan Bridge was built between 1901 and 1909 as the last of three bridges between Manhattan and Brooklyn. Unlike the Brooklyn Bridge with its stone towers and spidery suspension cables, or the Williamsburg Bridge that makes me wonder that it didn’t collapse of its own weight, the Manhattan Bridge is arguably the first modern suspension bridge, with its slender towers and a suspension system that was repeated in many bridges around the world. To be sure, it has its own problems. It is really two parallel suspension spans within a single structure. Each of these has two subway tracks above which is a two-lane roadway. The weight of the subway trains going over the bridge caused twisting in the parallel spans that led to extensive reconstruction starting in the 1980s. Between and supported by the parallel spans is a three-lane roadway.

A prominent figure in Tammany Hall, New York State Assembly Member George Washington Plunkitt, gave a series of interviews that were combined in the book Plunkitt of Tammany Hall, published in 1905. Plunkitt profited handsomely and unapologetically from the construction of the Manhattan Bridge. From the chapter entitled “Honest Graft:”

… supposin’ it’s a new bridge they’re goin’ to build. I get tipped off and I buy as much property as I can that has to be taken for approaches. I sell at my own price later on and drop some more money in the bank. Wouldn’t you? It’s just lookin’ ahead in Wall Street or in the coffee or cotton market. It’s honest graft, and I’m lookin’ for it every day in the year. I will tell you frankly that I’ve got a good lot of it, too.

The Manhattan Bridge has a pedestrian path on the west side and a bicycle path on the east side. Both are well used. I recall that on the Friday after Superstorm Sandy in 2012, the city’s Department of Transportation counted over 30,000 bikes on the bridge that day. I was responsible for two of those trips.

Manhattan Bridge footpath, looking toward Manhattan.

The architecture firm of Carrère and Hastings designed the New York Public Library’s main branch, many other buildings, and the Manhattan Bridge. Here is some of their design, marred by graffiti, at the Brooklyn anchorage of the bridge. The anchorages are where the main suspender cables are weighted down.

The Brooklyn tower of the Manhattan Bridge.

One of the great pleasures of not driving over the Manhattan Bridge is being able to take in the view, like this one.

View of the Brooklyn Bridge and Lower Manhattan.

Going into Manhattan the bridge goes over Chinatown and then into it.

East Broadway from the bridge.

The pedestrian path ends on the east side of the Bowery. Continue to Division Street, cross the Bowery, and turn left to cross Doyers Street. Doyers is a tiny, L-shaped street in the original part of Chinatown. Each of the city’s Chinatowns - the one in Manhattan and Chinatowns in Brooklyn and Queens - is worth a stroll and a blog post, and they will come.

Continue on the Bowery to where it becomes Chatham Square, crossing Mott Street and turning right onto Worth Street. Chatham Square is named for William Pitt, first Earl of Chatham and Prime Minister of Great Britain before the American Revolution. Chatham Square was once a major station on the Second and Third Avenue elevated lines. It and the area just to the west was a notorious 19th century slum called the Five Points, a focal point of the draft riots in 1863 and the setting for Jacob Riis’ How the Other Half Lives, published in 1890. This early example of photojournalism documented the squalid living conditions in the slums in the 1880s. One of the worst parts of the Five Points, known as the Bend, was later razed to make way for Columbus Park.

Columbus Park and Mulberry Street.

Across from Columbus Park on Mulberry Street are longtime Chinese funeral homes. I once got to see a traditional Chinatown funeral procession, I’m sure for a local big shot. The funeral party processed slowly on foot along Mulberry Street, led by middle-aged and elderly Italian-American men playing wheezy-sounding wind instruments. Nobody seems to know how this tradition came to be, it just did. Perhaps it is explained by the proximity of Chinatown to Little Italy, especially as Little Italy has been disappearing.

I continued west on Worth Street to Foley Square and turned left. Foley Square is named for Tammany Hall district leader and saloon keeper “Big Tom” Foley (1852 - 1925). Foley Square is Manhattan’s civic center, with state and federal court houses on the east side, the Federal Building and the U.S. Court of International Trade on the west side, a state office building on the northeast side, the Manhattan Criminal Court to the north of it, and the Municipal Building at the south end. Foley Square and the Five Points sit on the site of the Collect Pond, a source of fresh water for the city in the 18th century. From the website of the Lower East Side Tenement Museum:

Residents would spend time by the pond, picnicking in the summers and ice skating in the winter. This idyllic scene did not last long though, as the rise of industry started to affect New York City’s natural resource; the neighboring slaughterhouses, tanneries, breweries and other local shops began dumping their waste into Collect Pond. By 1800, the Pond was completely polluted, spreading cholera and other diseases to the city’s residents.

A canal was dug to drain the Collect Pond; it was later filled in and is now Canal Street. The African Burial Ground National Monument is just west on Duane Street; it is discussed in the post on this page entitled “City Hall Loop.” I walked through Foley Square, crossed to the west side of Centre Street, and continued to the end of the walk at the Brooklyn Bridge - City Hall subway station.

This was a beautiful day for a good walk. The walk across the Manhattan Bridge is very pleasant and offers picture-postcard views of Manhattan and New York Harbor. And the walk is 100 percent accessible.

Some Manhattan Bridge graffiti, from 2009 (top) and 2023.

Making a Guilder, a Pound, or a Buck

WHERE: Broadway and the eastern part of the Financial District in Lower Manhattan.

START: Fulton Transit Center: Fulton Street subway station (2, 3, 4, 5, A, C, J trains), fully accessible

FINISH: Bowling Green subway station (4, 5 trains), fully accessible

DISTANCE: 1.25 miles (2 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl except as noted. Map courtesy footpathmap.com.

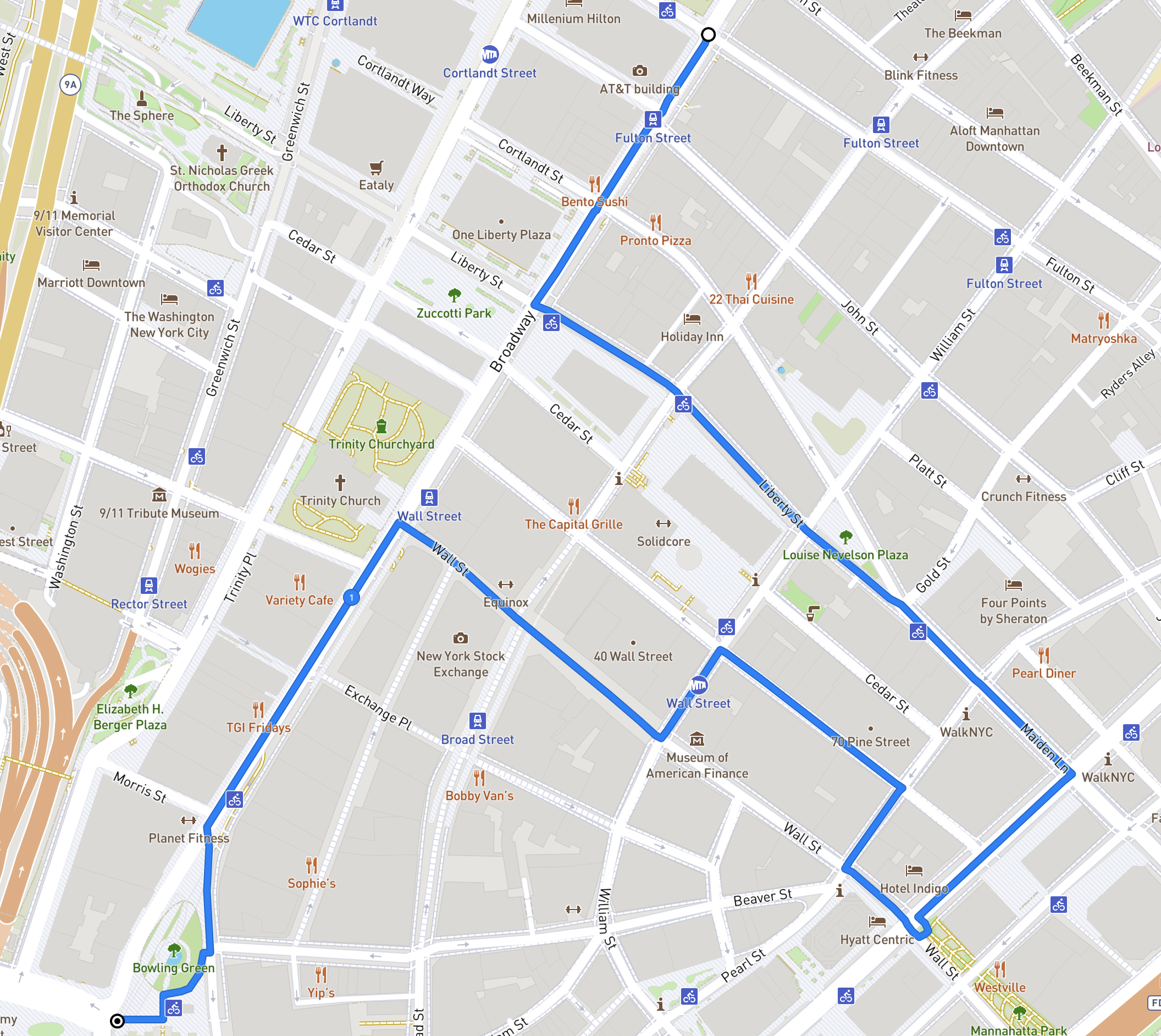

Route of this walk, going from top to bottom.

Some early arrivals in what is now New York City fled religious or political persecution - Deborah Moody in Brooklyn and Anne Hutchinson in the Bronx - and people still come to the city fleeing persecution. But New Amsterdam was founded by people seeking to make a few guilders, followed by the British wanting to make a few pounds, and after independence by people wanting to make a lot of dollars. This walk takes in some of that history. That seeking of riches came not only in the buying and selling of goods and financial instruments but in the buying and selling of human beings.

Starting at the Fulton Transit Center, turn left onto Broadway and walk south. This is the start of the “Canyon of Heroes” where dignitaries and celebrities have been treated to waste paper (ticker tape) being thrown out of upper story windows, an odd New York tradition, before arriving at City Hall to be presented with keys to the City. Stockbrokers used to get news of stock trades and prices on continuous strips of paper generated by “tickers.” Stock tickers are long out of use and ticker tape has to be specially ordered for these events. Every so often in the sidewalk you will see the commemoration of an individual or group that was treated to this sort of confetti, and the date on which it occurred.

Cross Liberty Street. Across Broadway is Zuccotti Park, where Occupy Wall Street staged a protest against economic inequality for 59 days in 2011. In front of you and to your left is 140 Broadway (1967) and Isamu Noguchi’s sculpture The Cube, whose tilt and red color play well against the smooth black skin of the building.

Turn left on Liberty Street. Across the street, near Nassau Street, is the former New York Chamber of Commerce (1902). The Chamber of Commerce moved to a somewhat less opulent location in Midtown Manhattan in 1979. The Chamber of Commerce of the State of New York was founded in 1768 as the first organization of its type in North America, and was granted a charter by King George III in 1770.

Cross Nassau Street. On your left is the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (1919 - 1924), by far the largest and most influential of the 12 regional Federal Reserve Banks. This building looks like it would take an Act of God to knock it down.

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York is uniquely responsible for implementing monetary policy on behalf of the Federal Open Market Committee and acts as the market agent of the entire Federal Reserve System (as it houses the Open Market Trading Desk and manages System Open Market Account). It is also the sole fiscal agent of the U.S. Department of the Treasury, the bearer of the Treasury’s General Account, and the custodian of the world’s largest gold reserve. Aside from these distinct functions, the New York Fed also performs the same responsibilities and tasks as the other Reserve Banks do, such as supervision and research. Once in a while there are special exhibits there; take advantage of them if you can.

Continuing past the Federal Reserve Bank, cross William Street to the triangular park on the opposite side. This is Louise Nevelson Plaza, home to several large sculptures by Louise Nevelson (1899 - 1988). Their Cubist forms contrast nicely with the surrounding buildings, notably the Federal Reserve Bank. Grab a seat and take it all in.

At the apex of Louise Nevelson Plaza, Liberty Street converges with Maiden Lane. According to The Street Book by Henry Moscow (New York, Hagstrom Company, 1978), the namesake was “a footpath beside a pebbly brook that ran from Nassau Street to the East River.” And, “Although the path (Maagde Paetje is Dutch for Maiden Lane) was a favorite strolling place for lovers, the name had a less romantic origin: the gentle grassy slope of the brook’s bank provided an ideal spot for washing and bleaching clothes, a chore assigned to young girls in most families.” Continue on Maiden Lane, crossing Pearl Street and Water Street, then turn right on Water Street.

In Colonial times Water Street was the East River waterfront. A landfill program began in 1692; Front Street (one block east of Water Street) and South Street (two blocks east) were built on the fill.

Continue to Wall Street. In the park on your left is a marker noting the site of New York’s slave market. Ships carrying human cargo docked at the wharf that was on this site. The slave market itself was established by the city one block inland, at Wall and Pearl Streets, in 1711. The slave trade was a major source of income for the Dutch West India Company, and the buying and selling of human beings continued in New York after independence. The city directly benefited from the sale of enslaved people by levying taxes on every person who was bought and sold there. Slavery was abolished in New York State only in 1827, but according to the NYC Parks website:

… complete abolition came only in 1841 when the State of New York abolished the right of non-residents to have slaves in the state for up to nine months. However, the use of slave labor elsewhere for the production of raw materials such as sugar and cotton was essential to the economy of New York both before and after the Civil War. Slaves also cleared forest land for the construction of Broadway and were among the workers that built the wall that Wall Street is named for and helped to build the first Trinity Church. Within months of the market's construction, New York's first slave uprising occurred a few blocks away on Maiden Lane, led by enslaved people from the Coromantee and Pawpaw peoples of Ghana.

In the above passage, “after the Civil War” refers to enslavement in other countries and to “sharecropping,” another name for indentured servitude, in the United States.

For more history of slave trading in New York City and the pro-slavery sympathies of New York’s business elite, go to https://www.nypl.org/blog/2015/06/29/slave-market.

Image courtesy New York Public Library,

Cross Water Street and walk west (uphill) on Wall Street. Wall Street gets its name from a wall, fortifications, and a ditch that were constructed at the northern boundary of New Amsterdam for defensive purposes, by white settlers and enslaved Africans. The wall and its fortifications were removed in 1699 as the city had grown beyond the wall.

On the Wall Street side of the building at the northwest corner of Pearl Street is a plaque noting that it was the site of the home, from 1784 - 1795, of Edward Livingston (1764 - 1836), who held many government positions, including that of Mayor of New York City, from 1801 - 1803. Without crossing Pearl Street, turn onto Pearl Street, walking north one block to Pine Street, then turn left. On your right is 70 Pine Street, which opened in 1932 as the Cities Service Building. Cities Service was an oil company that re-branded itself as CITGO in 1965. 70 Pine Street would be the last “skyscraper” to be built in Lower Manhattan until One Chase Manhattan Plaza opened in 1960. Until the construction of the new One World Trade Center, it was the tallest building in Lower Manhattan following the attack on September 11, 2001.

70 Pine Street, 2013. Photograph by Janine and Jim Eden.

At 60 Pine Street is the home of the Down Town Association. Built in 1887, this was the first purposely built private clubhouse in New York City. The membership has included the leading businessmen of New York, including many who went on to careers in public service. Women were not admitted as members until 1985.

Turn left on Nassau Street and continue to Wall Street. On your left is Federal Hall National Memorial, built on the site of New York’s first City Hall (1704), enlarged and renamed Federal Hall when New York was the capital of the United States (1788 - 1790) before moving to Philadelphia. The first two sessions of the First U.S. Congress met here. George Washington took his first oath of office as President here in April 1789. The present building opened in 1842 as the U.S. Customs House and later became the Sub-Treasury Building. There is an accessible entrance on Pine Street; go inside and look around.

Federal Hall National Memorial, 2019. Photograph by Ajay Suresh (Ajay Suresh from New York, NY, USA, CC BY 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons)

Across Wall Street on the left is the former headquarters of J.P. Morgan and Company (1913). In a grim precursor to September 11, 2001 this was the site of an anarchist attack in 1920 when a wagon load of explosives was ignited on the street, killing 33 and injuring some 400. Looking across Wall Street, down Broad Street on the right is the New York Stock Exchange (1903). Before the first World Trade Center bombing in 1993 there was a visitors center in the Stock Exchange that had a gallery looking out to the trading floor.

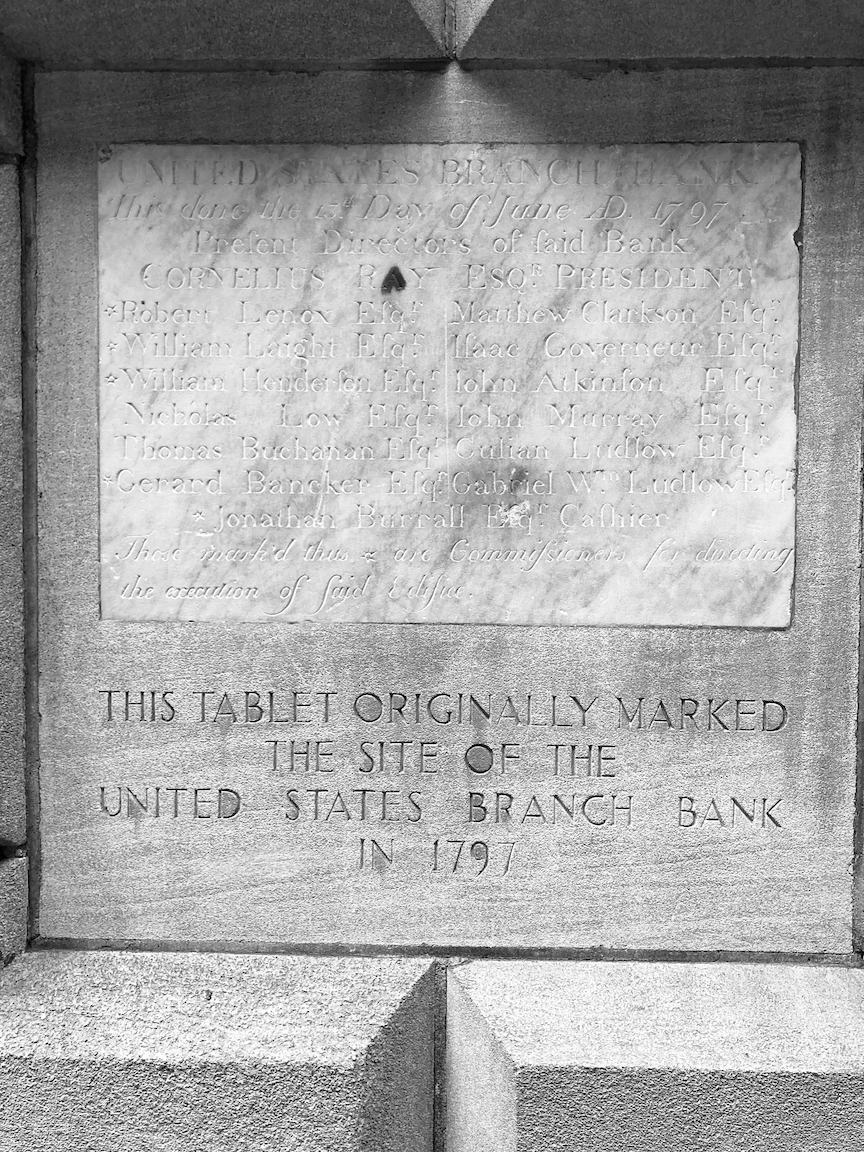

To your left on Wall Street is 40 Wall Street (1930), built as the headquarters of the Bank of the Manhattan Company, one of the predecessors of the present-day JPMorgan Chase and now called The Trump Building. This building was in a competition with the Chrysler Building to be the world’s tallest office building. After it was topped out the Chrysler Building’s distinctive spire was hoisted into place, giving it top honors. Just past 40 Wall Street is 48 Wall Street (1929), the former home of the Bank of New York, a corporate predecessor of the present-day BNY Mellon. On the facade is a tablet that marked the site of the United States Branch Bank in 1797. The Bank of the United States was established in 1791 to serve as a repository for federal funds and as the government’s fiscal agent. The Bank was based in Philadelphia with branches in eight cities.

From Federal Hall go uphill on Wall Street toward Broadway. On the left corner of Broadway is One Wall Street (1930), former home of the Irving Trust Company. If you can, get a look at the spectacular lobby. Across Broadway is Trinity Church. This, the third home of Trinity, was dedicated in 1846. Trinity received a land grant from Queen Anne in 1705 that covered Manhattan from modern-day Fulton to Christopher Streets and from Broadway to the Hudson River. Trinity has sold much of its granted property but retains a lot of it. Step inside the church and look around.

Trinity Church. Photograph courtesy bdcnetwork.com.

Continue south on Broadway: left from Wall Street, right from Trinity Church. Alongside Trinity churchyard there is a pair of original (1905) cast iron subway entrances.

Turning right on Rector Street, halfway down the block is a plaque marking the site of the first home of King’s College, founded in 1754, now Columbia University.

Farther down Broadway in the Charging Bull statue. Installed in 1989, it depicts a bull, the symbol of financial optimism and prosperity, leaning back on its haunches and with its head lowered as if ready to charge. It has been the occasional object of protests and vandalism, and has been likened by some to the Biblical golden calf. Children love to climb on it.

Photograph courtesy superiorwallpapers.com.

Just beyond is Bowling Green, New York City’s oldest park. Bowling Green was first designated as a park in 1733, when it was offered for rent at the cost of one peppercorn per year. Lessees John Chambers, Peter Bayard, and Peter Jay were responsible for improving the site with grass, trees, and a wood fence “for the Beauty & Ornament of the Said Street as well as for the Recreation & delight of the Inhabitants of this City.” A gilded lead statue of King George III was erected here in 1770, and the iron fence (now a New York City landmark) was installed in 1771. After the reading of the Declaration of Independence on July 9, 1776, a mob that included Alexander Hamilton (King’s College class of 1776) pulled down the statue and melted down much of it for musket balls. The king’s crown from the statue resides to this day in the Trustees’ Room at Columbia University’s Low Memorial Library.

Linger in the park. Think of all the history that is all around you. From here take the elevator or stairs down to the Bowling Green subway station.

City Hall Loop

WHERE: A loop around City Hall Park in Lower Manhattan.

START/FINISH: Fulton Transit Center: Fulton Street subway station (2, 3, 4, 5, A, C, J trains), fully accessible

DISTANCE: 1.1 miles (1.8 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl except as noted. Map courtesy footpathmap.com.

Map of this walk, starting and finishing at lower left.

Lower Manhattan is where New York began, with the settlement of New Amsterdam, founded by the Dutch West India Company in 1626. In 1664 Britain took over, the Dutch trading post became English, and it acquired a new name, New York. Until well into the 20th Century Lower Manhattan was the business center of the city - it is still called the Financial District - and it remains the location of many city, state, and federal government functions. Yet many older office buildings have “gone residential” or been converted to hotels or other uses. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, many large offices migrated to newer buildings with large floor areas. Arguably there was too much office space before the pandemic, and the future of office work is unsettled. Yet Lower Manhattan evolves.

Start at the Fulton Transit Center, at the southeast corner of Broadway and Fulton Street. This was built in the years following the attacks on September 11, 2001, to improve connections among, and bring accessibility to, the four subway stations there. The Fulton Transit Center is a qualified success; transferring from one station to another is certainly clearer than it was, and numerous elevators and escalators make the whole complex more easily navigable. It is also connected, by a passageway underneath Dey Street, to the World Trade Center transit hub (1, E, R subway lines and PATH trains to New Jersey). But the four subway stations, which opened in 1905 (4 and 5 trains), 1919 (2 and 3 trains), 1931 (J train), and 1933 (A and C trains), were never designed to connect easily with each other. The placement of the J train station in particular makes the whole complex still problematic. Nevertheless, it is much better than it was.

Exiting the Fulton Transit Center, cross Fulton Street and walk north on Broadway. On the left is St. Paul’s Chapel, built between 1764 and 1766 as an outpost of Trinity Church a few blocks south on Broadway. Its wooden steeple was buiilt betwen 1794 and 1796. It is the only extant pre-Revolutionary building in the original city of New York. Miraculously, St. Paul’s had only minor damage from the collapse of the World Trade Center towers, and was a gathering place for rescue workers. President George Washington worshipped here.

The steeple of St. Paul’s Chapel with the World Trade Center in the background, 1981.

Cross Ann Street and Park Row (going diagonally to the right), continuing to City Hall Park, then turn right. In pre-Revolutionary times the space occupied by City Hall Park, City Hall, and the area between City Hall Park and Chambers Street was known as the Commons. The AIA Guide to New York City, Fifth Edition (2010), notes “Buildings, seemingly for random purposes at random locations, occupied pieces of this turf from time to time.” The park itself was the site of the General Post Office from 1871 to 1938. The fountain in the park is a reproduction of the fountain that was moved to Crotona Park in the Bronx to make way for the Post Office. We will note the locations of other such random buildings along the way.

Park Row was not only the eastern boundary of the Commons, it was also the southern end of the Boston Post Road, which for most of its length is U.S. Route 1. At Spruce Street, cross Park Row to see the statue of Benjamin Franklin, noting his work as a printer and dating from 1872. The intersection of Park Row, Spruce Street, and Nassau Street is known as Printing House Square, and the east side of Park Row used to be known as Newspaper Row as severtal of the city’s newspapers had their offices and were printed there.

Cross Park Row back to the City Hall Park side and turn right. On the left you’ll see Steve Flanders Square, named for the reporter (1918 - 1983) from radio station WCBS who covered City Hall for decades. City Hall dates from 1812 and has been altered several times. When built it was near the northern edge of the city, and while the southern facade was clad in marble the northern facade was constructed of less costly material. Today, the facade is uniform (limestone) all the way around. The most ornate room is the Council chamber. The Mayor doesn’t always work from City Hall; Michael Bloomberg, when he was Mayor (2002 - 2013) worked from the Tweed Courthouse directly behind City Hall.

Continue past the entrances to the Brooklyn Bridge - City Hall subway station. Notice an ornate entrance to the elevator leading down to the subway station. This is a reproduction of the shelters, known as kiosks, over the stairways to the stations on the first subway, which opened in 1904.

Across Park Row is the Brooklyn Bridge. At one time the view of the bridge was obscured by a terminal for Brooklyn elevated trains. Immediately north of that terminal was the City Hall terminal of the Second and Third Avenue elevated railways. Both terminals were demolished in the 1950s. There has long been a lot of transportation at this location.

In the park on the right there is a stone marker noting some of the structures built in the Commons in the 18th century: the Almshouse for the poor, military barracks, the New Gaol (British spelling of “jail” with the same pronunciation) on the site of the marker, and another prison called the Bridewell, facing Broadway.

From Archaeology Archive:

The New Gaol, erected in 1759, was built in response to New York City’s growing crime problem. The three-story masonry building in the northeast of the Commons was originally intended to house convicted criminals, but served multiple functions throughout its history. The new building was soon used for debtors and prisoners-of-war during the French and Indian War. Its location next to the Almshouse and its growing use for debtors soon led to the appellation “the debtor’s prison.” A continuing rise in crime and the resultant overcrowding of the New Gaol led the city to begin construction of the Bridewell in 1773, where some felons were moved two years later. During the Revolutionary War, the Gaol was crowded with American prisoners. After the War, the building was returned to its earlier function of housing felons and debtors, the latter of whom paid for their own clothing, food, and fuel. The Gaol continued to house prisoners until 1824. It was slated for demolition, but was eventually refurbished and converted to a Hall of Records for the city in 1830. The building was torn down in 1903, at which time it was the oldest civic building in New York City.

The Hall of Records, formerly (without the classical portico) the New Gaol, demolished in 1903. In the foreground is the overpass to the Brooklyn Bridge terminal. In the right background is City Hall. In the left background is the General Post Office, demolished in 1938. Photo courtesy New York City Municipal Archives.

Constructed in 1775, the Bridewell was meant to be a debtor’s prison and workhouse. However, for the duration of their occupation during the Revolution the British used the building as a prison for American prisoners of war. During the War of 1812, the occupying British again used the Bridewell as a place to house prisoners of war. It was only after the War of 1812 that the Bridewell returned to its original purpose as a general city jail.

The most famous inmate at the New Gaol was William Duer, known as the first Wall Street villain and a key figure in the Panic of 1792. The Bridewell got its name from a jail of the same name in London.

To your right, across Centre Street, is the Municipal Building, which opened in 1914 and houses many city offices. It straddles Chambers Street, and through the archway one can see the headquarters of the New York Police Department, One Police Plaza (1973). Atop the colonnade in front of the Municipal Building is inscribed NEW AMSTERDAM MDCXXVI. then MANHATTAN, then NEW YORK MDCLXIV. Look up.

Cross Chambers Street. On your left is the Surrogate’s Court, which opened in 1907. In New York State the Surrogate’s Court is sometimes referred to as “widows and orphans court” and adjudicates disputes concerning estates. Cross Reade Street. To your right is Foley Square, around which are state and federal court houses on the east side, and the Federal Building and Court of International Trade on the west side.

Surrogate’s Court.

Turn left onto Duane Street. At the corner of Elk Street is the African Burial Ground National Monument. During the construction of the Ted Weiss Federal Building in the early 1990s, over 400 sets of human remains were discovered. This area had been a burial ground, just north of the old city limits, for over 20,000 “Negroes” in the 17th and 18th centuries, Read the interpretive signage. then walk through the monument. This is a moving memorial and tells a chapter of this city’s history that is not known enough.

Two views of the African Burial Ground National Monument. In the upper image, the inscription reads “To all those who were lost, For all those who were stolen, For all those who were left behind, For all those who were not forgotten”

Turn onto Elk Street and walk the two short blocks to Chambers Street, then turn right. The first building on the right is the former Emigrant Industrial Savings Bank (1908 - 1912), now an exhibition space called Hall des Lumieres. Across Chambers Street is the former New York County Courthouse, better known as the Tweed Courthouse (1861 - 1872). The construction “cost” was over $14 million, exorbitant for the time. The de facto mayor of New York, William Marcy (“Boss”) Tweed, who headed the New York County Democratic organization (Tammany Hall), pocketed some $10 million of that total. Today the building is used as municipal offices.

Continue walking toward Broadway. On the right is a white-painted building that was built as the A.T. Stewart Dry Goods Store (1845 - 1846), the first great department store. Stewart is perhaps better known for developing Garden City, Long Island in the 1870s. Stewart’s store was taken over by the New York Sun newspaper, which installed the ornate clock on the corner of the building that reads “The Sun It Shines for All.” The building is now occupied by the New York City Department of Buildings.

Cross Chambers Street onto the east (park) side of Broadway. In the park near Warren Street there is a set of foundation stones. These are what is left of the Bridewell, which stood on this site. In the sidewalk there is a plaque noting the location of the British army barracks.

Continue walking and on the left is a plaque pointing to a flagpole erected to commemorate the five Liberty Poles built in the Commons during the Revolution, as a rebuke to the British occupiers.

Liberty Poles plaque, foundation stones of the Bridewell to the left.

Across Broadway at Park Place is the Woolworth Building (1913). When it was completed, and until the completion of 40 Wall Street and the Chrysler Building in 1930, it was the world’s tallest office building. It was the longtime headquarters of the now defunct F.W. Woolworth Company and was known as the “Cathedral of Commerce.” If you ever get the chance to take a guided tour of the lobby, do so.

Continue down the same side of Broadway to end at the Fulton Transit Center, or relax in City Hall Park, or take a moment for quiet contemplation in St. Paul’s Chapel.

This short walk packs in a lot of architectural and historical interest and begins a look at the exploitation of African-Americans, something to which we will return on future walks.

The Joy of Strolling

This very nice piece appears in The New York Times. “Flâneur” is French for one who strolls. Enjoy and go out for a stroll, not necessarily “from Point A to Point B.” You’re almost certain to discover something or someone new.

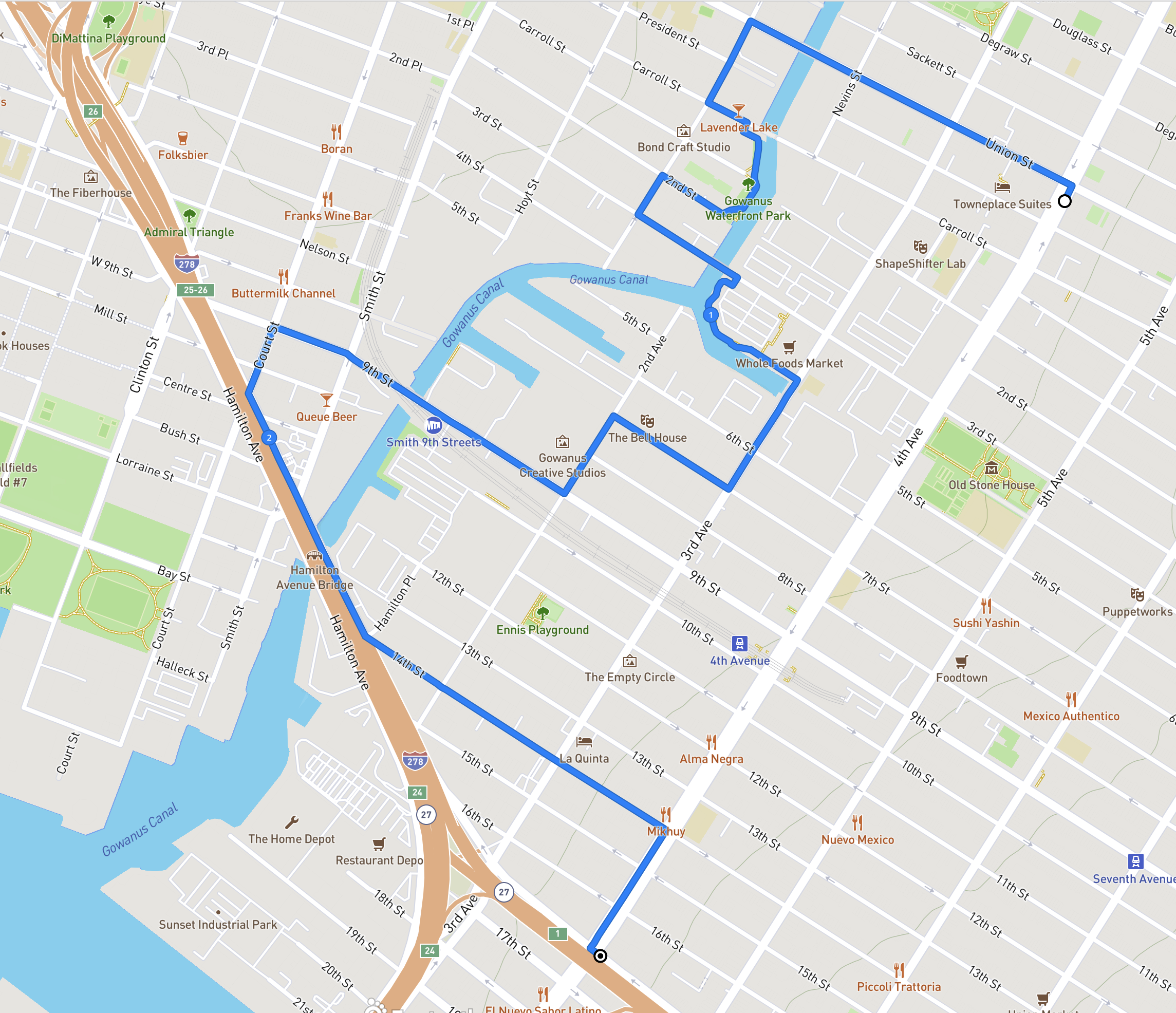

Gowanus Zigzag (Brooklyn)

WHERE: The bridges across the Gowanus Canal at Union Street, 3 Street, 9 Street, and Hamilton Avenue, Brooklyn

START: Union Street subway station (R train)

FINISH: Prospect Avenue subway station (R train)

DISTANCE: 2.8 miles (4.5 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl except as noted. Map courtesy footpathmap.com.

Route of this walk, reading from top to bottom.

The Gowanus Canal is a narrow, polluted waterway, in fact a Superfund site, that snakes its way from New York Harbor into Brooklyn. During the Battle of Brooklyn in August 1776, George Washington led the retreat away from what is now Prospect Park, past the Old Stone House in what is now Park Slope, across the Gowanus Creek and then to Manhattan. The Gowanus Creek was turned into a navigable waterway in the mid-ninetenth century and was lined with industry. Pollution was a problem early on, and the smell was so bad that the canal earned the derisive name “Lavender Lake.” Early in the twentieth century a water tunnel was built to connect the north end of the canal with the harbor, and a flushing mechanism was installed at the north end to circulate water through the canal. In recent years the flushing mechanism, long out of service, was rebuilt and its capacity was increased.

In the mid-1990s local businessman and civic activist Salvatore “Buddy” Scotto (1928 - 2020) led a walk through the Gowanus neighborhood that I took part in, where he expressed his vision of a Gowanus Canal that would be revitalized like the Riverwalk in San Antonio, Texas. A lot of people then thought Buddy was crazy but he held fast to his vision and lived long enough for the first bits of it to fall into place. Interestingly, Buddy was a vociferous opponent of the Superfund designation, fearing it would deter development. New buildings have sprouted anyway. The grittiness of Gowanus is not so slowly disappearing and perhaps can be seen as a logical consequence of new apartment towers lining once shabby Fourth Avenue and in Downtown Brooklyn.

A personal reminiscence of Buddy Scotto: He was one of those civic activists I could hug and strangle in the same sentence. We tilted swords more than once but we could disagree without being disagreeable. In 2012 he and I were among the honorees as “Kings of Kings” (as in Kings County), hosted by a local media company. At the awards ceremony (it was at a catering hall in the Mill Basin neighborhood called El Caribe) I stood next to Buddy as he was being interviewed. He asked the interviewer, “Why am I here?” I said, “Because you’re you, Buddy.”

This walk took in the four walkable bridges over the canal. A fifth, the Carroll Street Bridge, is closed to all traffic “until further notice” for repairs. Starting at the Union Street subway station, there is a new apartment tower on 4 Avenue where there was an empty lot next to an old municipal bathhouse that has been repurposed. For years an old Philadelphia streetcar lay in the empty lot. I do not know how or why it ended up there. On the northwest corner of Union Street and Fourth Avenue, what was the site of a filling station has an apartment block going up. Walking west on Union Street, I passed the Dinosaur Bar-b-Que, the Brooklyn outpost of Dinosaurs in Syracuse and Rochester, then a Holiday Inn Express that has become a shelter for asylum seekers, and a store selling African drums. As I walked by I enjoyed the sight and sound of two men drumming away on the sidewalk.

Crossing 3 Avenue and then Nevins Street, I came to the first of this walk’s bridges, the Union Street Bridge. This is a very short double-leaf draw bridge. The last canalside industrial user, the Bayside Fuel Oil depot just north of the bridge, closed and that site is being redeveloped. I doubt the Union Street Bridge and the very similar 3 Street Bridge will ever have to be opened again, except in connection with the Superfund cleanup.

View south on Nevins Street south from Union Street, toward apartment towers under construction.

View north from the Union Street Bridge, toward the former site of the Bayside Fuel Oil depot.

View south from the Union Street Bridge toward the Carroll Street Bridge.

Once across the Union Street Bridge, I turned left onto Bond Street, going for two blocks to Carroll Street. The little Carroll Street Bridge opened in 1889 and is one of two retractable bridges in New York City, the other being the Borden Avenue Bridge in Queens, described in my post “Newtown Creek Walk #1” on this page. It is closed “until further notice for repairs” and I only hope it is repaired and brought back to life. A retractable bridge does not swing up, or pivot in the center. The draw span moves on rails into a berth alongside, an elegant solution for a very narrow waterway.

The Carroll Street Bridge in 2020, before it was closed. The sign to the right of the yellow clearance sign, a re-creation of the original. reads “By Order of the City, Any Person Driving Over this Bridge Faster Than a Walk Will Be Subject to a Penalty of Five Dollars for Each Offence.”

At the west end of the Carroll Street Bridge, a nice canalside path begins and goes south to 2 Street, two blocks. I’m sure Buddy Scotto approved.

The canalside promenade south of Carroll Street. The large building in the background is the former Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company electric power station, built 1901 - 1903, derelict since its abandonment in 1972, and recently reopened as a stunning new arts and events venue called Powerhouse Arts. In its early days, coal was delivered to the power station on barges on the canal.

From the south end of this promenade I made my way to the Third Street Bridge and to another canalside promenade, this one having been built together with the Whole Foods Market on 3 Street. The sight of those apartment towers in a once industrial area has a more than passing resemblance to the very similar transformation of the Mott Haven section of the Bronx.

View north from the 3 Street Bridge.

View south from the Whole Foods promenade, with the canal turning to the right and the 4 Street Basin to the left.

“Feast or Famine” at Whole Foods.

The former can factory on 3 Avenue, more recently a space for artists’ studios.

From the end of the Whole Foods promenade I turned onto 3 Avenue and then right onto 7 Street, into a not yet redeveloped part of Gowanus. On this block is the Bell House, which National Public Radio listeners will recognize as the home base for the game show “Ask Me Another” and as the frequent venue for the storytelling series “The Moth Radio Hour.”

The Bell House.

On 2 Avenue is the former Kentile Floors factory, now artists’ studios. For decades the Kentile sign was a local landmark.

Photo courtesy ny.curbed.com

I turned west onto 9 Street and the 9 Street Bridge, which is underneath the highest subway station in the city, Smith - 9 Streets (F and G trains). Less than a decade ago the MTA refreshed this station but inexplicably passed up the opportunity to make it accessible.

The 9 Street Bridge underneath the Smith - 9 Street subway station.

View north from the 9 Street Bridge.

Wrought iron fence on West 9 Street.

Crossing Smith Street, I continued for a block on West 9 Street, one of two West 9 Streets in Brooklyn (the other is in southern Brooklyn), then left on Court Street to Hamilton Avenue. Hamilton Avenue is a wide, ugly thoroughfare underneath the elevated Gowanus Expressway (Interstate 278). I would not have ventured there at all but for the southernmost bridge over the Gowanus Canal, at Hamilton Avenue. This bridge is two double-leaf draw spans. one for northbound traffic (toward Manhattan) and one for southbound traffic. The New York City Department of Transportation has talked for years about creating a protected bike lane on the southbound span as part of the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway, similar to what was done on the Pulaski Bridge between Long Island City and Greenpoint, but nothing has been done and whatever plans exist lie on a shelf somewhere, gathering dust.

Looking toward the Hamilton Avenue Bridge from Smith Street.

View north from the Hamilton Avenue Bridge. The elevated Smith - 9 Streets subway station and, beneath it, the 9 Street Bridge, are in the background.

From the southern end of the Hamilton Avenue Bridge I walked east on 14 Street, past a Sanitation Department garage, some light industry, and some homes, to 4 Avenue, whence I turned right to the end of the walk, the Prospect Avenue subway station. This station was recently freshened up under the Enhanced Stations Initiative launched by former Governor Andrew Cuomo. While the station looks nicer than it did, this was yet another missed opportunity for accessibility.

I had not done an extended walk through Gowanus since the early days of the pandemic, and I had never set foot on either of the canalside promenades. It is certainly an area in flux. The area south of 3 Street has not seen the burst of new construction that characterizes the Gowanus Canal north of the 3 Street Bridge. It will. I hope places like artists’ studios, the Bell House, lumber yards, and U-Haul will not be swept away. A lot of people in the community work in these places and the light industry that still dots the landscape. And new housing has to have a large percentage of truly affordable units for people who have been or will have been priced out elsewhere. This is the challenge for the ongoing re-zoning of Gowanus: preserving (and encouraging) jobs and a mix of uses; providing quality, truly affordable housing; all in an accessible environment. This is not inconsistent with Buddy Scotto’s vision or what the city needs.

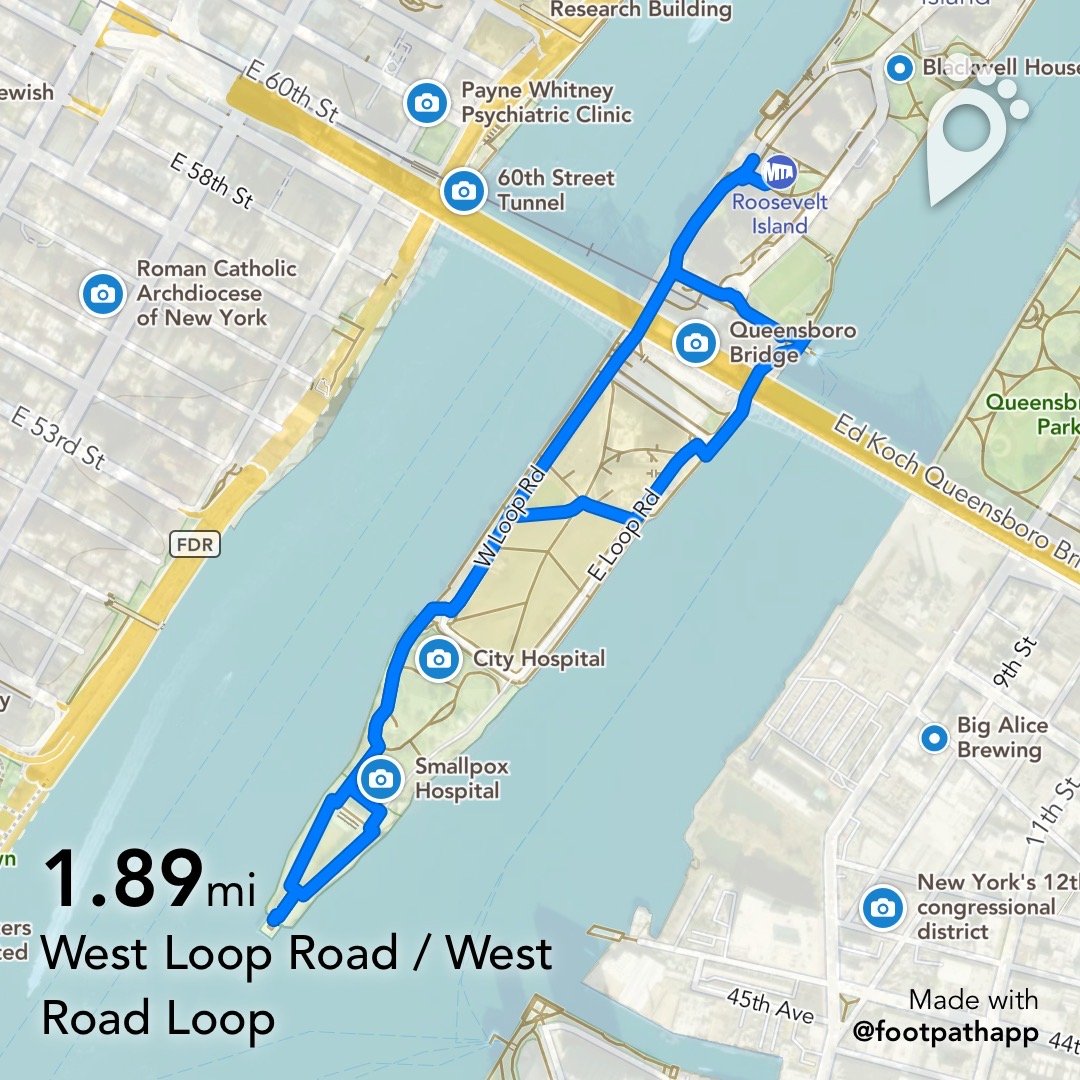

Crossing the Hudson at Poughkeepsie, New York

WHERE: The Mid-Hudson Bridge and the Walkway Over the Hudson

START/FINISH: Poughkeepsie station (Amtrak and Metro North Railroad, Hudson Line), fully accessible

DISTANCE: 3.1 miles (5 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl. Map courtesy Google Maps.

Roout of this walk.

This was a walk I had had in mind for a long time and finally did. I had biked across the Mid-Hudson Bridge in 1993 and had never been on the Walkway Over the Hudson.

Poughkeepsie (pronounced po-KIP-see) is a small city on the east bank of the Hudson River, midway between New York City and Albany. The train ride between the two cities is one of the most scenic in the United States and is along the Hudson shoreline almost the entire way. Along the way we passed Sing Sing prison in Ossining, the village of Cold Spring where many of the Union Army’s cannons were produced in the Civil War, the ruins of Bannerman’s Castle just south of Beacon, and, on the opposite shore, Bear Mountain and the United States Military Academy at West Point. Poughkeepsie is home to Vassar College and Marist College, and is the county seat of Dutchess County.

The walk began at Poughkeepsie’s beautiful train station, whence we made the short walk to the Mid-Hudson Bridge. Dedicated by New York Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1930, this bridge carries U.S. Route 44 to Highland and on to New Paltz.

At the bridge towers there is a site-specific work, Bridge Music by Joseph Bertolozzi, composed entirely of sounds from the bridge and commissioned for the 400th anniversary (2009) of Henry Hudson sailing up the river that bears his name. For more information on the composer and his work, visit https://josephbertolozzi.com/bridge-music/

Link to Bridge Music on Apple.

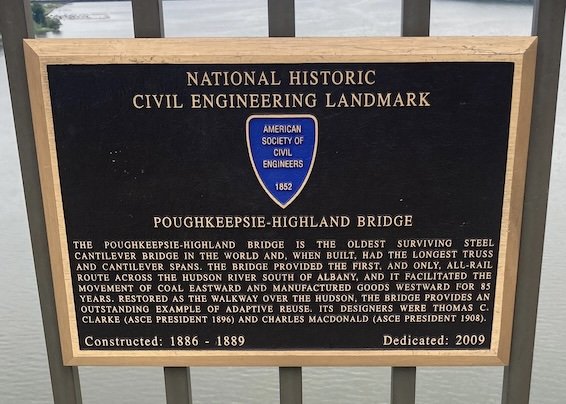

The Mid-Hudson Bridge from Johnson-Iorio Park on the west bank.

From the western end of the bridge we walked uphill along Haviland Road to the Walkway Over the Hudson, the entry to which is a pleasant little plaza with a pavilion reminiscent of an old railroad station. The Walkway is on a former railroad bridge, the Poughkeepsie-Highland Bridge, which opened in 1889 and was an important freight connection for the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad, and later the Penn Central Railroad, until a fire in 1974 closed it to traffic. The bridge lay derelict for many years until local activists succeeded in getting the bridge restored as a bike and pedestrian path. The Walkway opened in 2009 and has become extremely popular.

The Walkway Over the Hudson, seen from the Mid-Hudson Bridge.

The Mid-Hudson Bridge, seen from the Walkway Over the Hudson.

The Walkway is beautiful and wide, with benches at intervals where one can sit, relax, and enjoy the sweeping views. At the east bank of the river there is an elevator down to a riverfront park. The Walkway continues east to the east side of Poughkeepsie.

From the bottom of the elevator we continued to lunch at the River Station restaurant and then to the train back to the city.

While this walk was not particularly long and was not too physically taxing, the views, the Bridge Music, the getaway from the city, and the good company made it exhilarating and worth a repeat visit. I have certainly done more taxing walks but this one gave me particular satisfaction.

At lunch at the end of the walk, clockwise from left: Yours Truly, Matt, Mia, Vaughan, Gary, Mike.

Bronx Park

WHERE: A portion of Bronx Park

START: Botanical Garden station (Metro North Railroad, Harlem Line), fully accessible, also Bx26 bus

FINISH: Gun Hill Road subway station (2 train), fully accessible; also Bx39, Bx41 buses

DISTANCE: 1.5 miles (2.4 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl except as noted. Map courtesy footpathmap.com.

Route of this walk, reading from left to right.

On a map Bronx Park appears roughly as a triangle, much of the lower part taken up by the Bronx Zoo and the New York Botanical Garden, adjoining the Rose Hill campus of Fordham University. There is still much of it that is just a public park. On this walk we will traverse the northern part of Bronx Park.

The Bronx River runs north to south through the park. Through the efforts of the Bronx River Alliance the Bronx River Greenway is being created and the Bronx River is being cleaned up and made open to the public. This walk takes us along a portion of the Bronx River Greenway, including a crossing of the Bronx River. Other walks on this site cover other portions of the Greenway.

Part of this walk also takes us through the Bronx River Parkway Reservation. The Bronx River Parkway Reservation is a linear park that includes recreational facilities, preserved and restored natural areas, and a road that is restricted to private passenger vehicles. The Reservation parallels the Bronx River for 15.5 miles (25 kilometers) from the New York Botanical Garden north to Kensico Dam at Valhalla in Westchester County. The parkway extends 12.5 miles (20 kilometers) in Westchester County and its original section, from the New York City limits south to Burke Avenue, another 3 miles (5 kilometers). According to the Historic American Enginering Record:

The Bronx River Parkway Reservation was the first public parkway designed explicitly for automobile use. The project began as an environmental restoration and park development initiative that aimed to transform the heavily polluted Bronx River into an attractive linear park connecting New York City’s Bronx Park with New York City’s Kensico Dam and reservoir. With the addition of a parkway drive the project became a pioneering example of modern motorway development. It combined beauty, safety, and efficiency by reducing the number of dangerous intersections, limiting access from surrounding streets and businesses, and surrounding motorists in a broad swath of landscaped greenery.

In addition to reclaiming the Bronx River, the Bronx Parkway Commission (BPC), as it was called, cleaned each parcel of land as soon as it acquired title. The BPC immediately instituted a forestry program. “The condition of the trees in this section of the country,” the BPC noted, was “cause for grave concern.” Prompt measures were necessary.

The BPC hired a forester, Albert N. Robson, who was noted for his experience in tree care. In addition, the commission engaged Hermann Merkel, a landscape architect and forester at the Bronx Zoo and Botanical Gardens, who was considered to be a recognized authority on various tree pests. Robson’s and Merkel’s first year with the commission resulted in 13,018 dead trees being removed, 5,037 trees trimmed, and 16,039 trees improved and reclaimed by surgery.

Construction of the Bronx River Parkway began in 1908. It was completed as far south as Burke Avenue in 1925 and the extension to Story Avenue in the south central Bronx opened in 1951.

I started the walk on this picture-perfect Memorial Day at the Botanical Garden railroad station, across the street from the New York Botanical Garden. The Botanical Garden is worth its own blog post at the very least. From there I walked north on the footpath that parallels Southern Boulevard, crossed Mosholu Parkway, and continued north on the path, following the Bronx River Greenway/East Coast Greenway arrow.

Going left at the arrow and continuing past baseball fields on the right, I passed French Charley’s Playground. Who exactly was French Charley? The NYC Parks website has the answer: “This playground honors the memory of Charley Mangin who owned a nearby French restaurant in the 1890s. His establishment, in the heart of a small French enclave of the Bronx, was popularly referred to as French Charley’s. After the restaurant closed down, a ball field and picnic area were built near the site and people began to refer to the site as French Charley’s Field.” This has become a playground and picnicking area.

From there I continued on the path, following the arrows, through the Bronx River Forest, a remnant of the original forests and floodplains that once blanketed the Bronx River corridor. The path crosses the Bronx River on the Burke Avenue Bridge, then ducks underneath the Bronx River Parkway.

Path through the Bronx River Forest.

Bronx River Parkway underpass.

Past the Parkway I turned left, and across from the Rosewood Playground was a stone monument. The near (south) side is missing a plaque that was engraved thus and memorializes the huge undertaking that was the construction of the Bronx River Parkway, not just the road of that name.