Tribeca to Greenwich Village (Manhattan)

WHERE: The lower West Side of Manhattan

START: Chambers Street subway station (1, 2, 3 trains); fully accessible

FINISH: 14 Street - 8 Avenue subway station (A, C, E, L trains); fully accessible

DISTANCE: 2.45 miles (3.9 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl. Map courtesy footpathapp.org.

Route of this walk, reading from bottom to top.

The days immediately following the year-end holidays are a good time to hit the streets of Manhattan without being overwhelmed by traffic. So on the first Saturday of 2023 I chose a walk without hills, stair streets, or walkable bridges, but with plenty to make me stop and look. I chose a walk that started in what was once just the lower West Side but in the 1980s was re-branded “TriBeCa” for Triangle Below Canal Street, that would end with a zigzag through Greenwich Village. The course was flat and, with some qualifications, accessible.

Coming out of the subway at the intersection of Chambers Street, Hudson Street, and West Broadway, I was greeted by a public plaza in what used to be the southernmost block of Hudson Street.

Looking east on Reade Street from Hudson Street. I saw this painted sign that has baffled me for years.

A block north was the evolution of this neighborhood in one visual: a nicely restored nineteenth century building on the corner, the great Western Union building of 1930 (Ralph Walker, architect), and a modern residential tower designed by Frank Gehry in the right background.

A block north is little Duane Park, one of my favorite spots in the city. The loft buildings on the south side of Duane Street used to be home to wholesalers of eggs, milk, and butter. Such clusters of food wholesalers once were found around Manhattan, near the Hudson River or East River. Eventually, these businesses relocated to modern facilities at Hunts Point in the Bronx.

Leading north from Duane Street is two-block long Staple Street, another favorite of mine. From The Street Book by Henry Moscow (Hagstrom Company, 1978):

The Namesake: staple products that were unloaded there. Under Dutch law that was effective in New Netherland, ships in transit had to pay duty on their cargo or offer the cargo for sale. In New Amsterdam, Staple Street was the marketplace for such goods.

Staple Street is beguiling: narrow enough that one can, and should, walk safely in the street and not on the too-narrow sidewalks. At the north end is the onetime home of the New York Mercantile Exchange.

Staple Street, looking north.

Former New York Mercantile Exchange, Harrison Street west of Hudson Street

From Staple Street I turned right onto Harrison Street and left on Hudson Street. At Hudson and North Moore Streets is a popular restaurant called Bubby’s, with a line to get in for brunch.

The Saturday brunch queue at Bubby’s.

This part of Manhattan used to be home to food wholesaling as noted before, plus suppliers to the maritime industry when the Hudson River shoreline was a phalanx of docks from the Battery to 59 Street, and other light industry. That didn’t prevent individual buildings from having artistic flourishes; witness the Mercantile Exchange and the corner of this building at Beach and Hudson Streets.

At this point, on the east side of Hudson Street is the exit plaza for the Holland Tunnel. This plaza was built on the site of St. John’s Park. Continuing north, cross Canal Street, turn left, and then turn right onto Renwick Street. This one-block street has seen a lot of change in recent years, not limited to the new building on the left.

Renwick Street, looking north.

At the end of Renwick Street, turn left onto Spring Street and cross Greenwich Street. Ahead is a fine, favorite old watering hole, the Ear Inn. It is in a building constructed around 1770 and became the home of James Brown, an African aide to George Washington in the Revolutionary War and, later, a successful tobacco merchant. More history of the Ear Inn is at http://www.theearinn.com/about. When it was built the Hudson shoreline was just to the east of where Washington Street is now and just west of the Ear Inn.

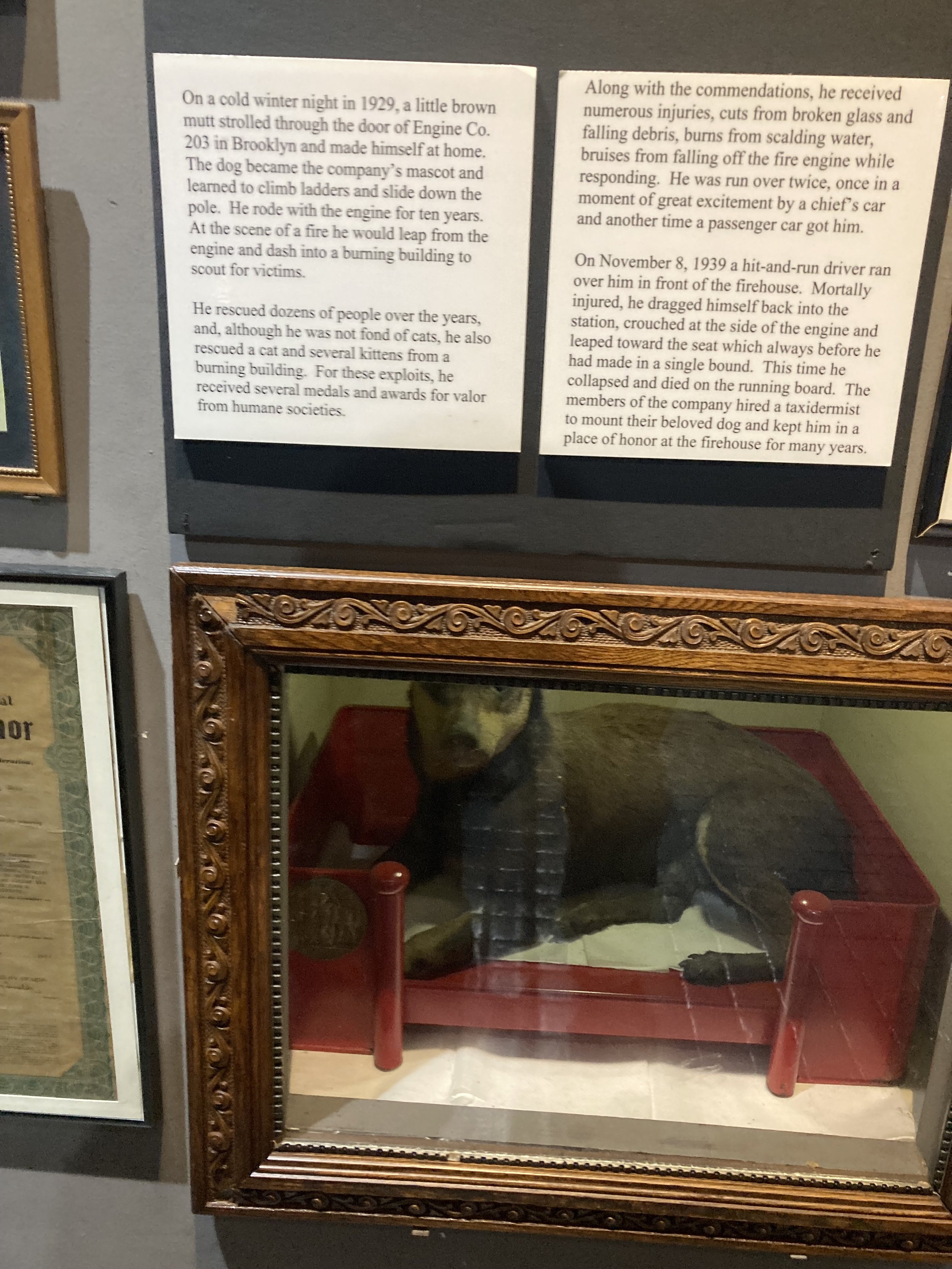

Turning around and walking east on Spring Street, past Hudson Street, I came upon the New York City Fire Museum. I had walked past it many times but had never gone inside until this day. It is completely accessible and is well worth a visit. It has a lot of old fire fighting equipment and other paraphernalia, plus an excellent, heartbreaking permanent exhibit of artifacts from the World Trade Center and a tribute to the 343 New York City fire fighters who died in the attack on September 11, 2001.

There’s a section of the museum devoted to fire house dogs.

From Spring Street the walk continued left (north) on uninteresting Varick Street. I turned right (east) onto Carmine Street for a block, then turned left (north) onto narrow Bedford Street. Crossing 7 Avenue South and staying on Bedford Street, be on the sidewalk on the right side as the other sidewalk is just too narrow. Turn left onto Commerce Street and see the Cherry Lane Theatre, a celebrated Off-Broadway stage.

Cherry Lane Theatre on Commerce Street.

From Commerce Street I turned right (east) on Barrow Street, then left (north) on Seventh Avenue South. This street didn’t exist prior to the IRT subway being constructed in the 1910s. The large number of empty storefronts and once busy restaurants testify to how hard the pandemic has been on small businesses.

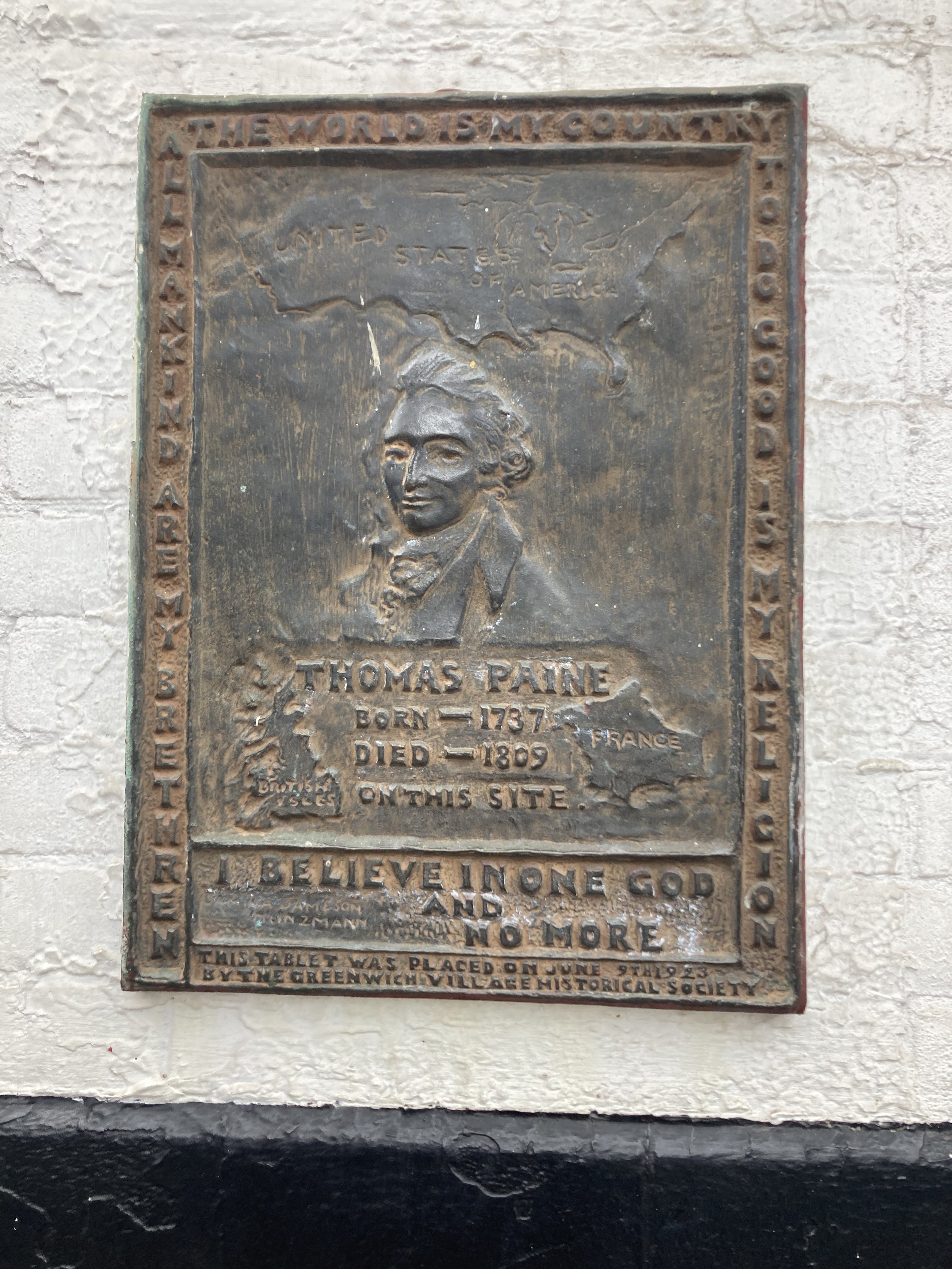

Off to the left are Marie's Crisis Cafe and a jazz and blues venue called Arthur’s Tavern. On the facade of Marie’s Crisis was this example of history hiding in plain sight. Thomas Paine wrote a series of pamphlets during the American Revolution under the banner of “The American Crisis” and this is the Crisis in Marie’s Crisis Cafe, not any crisis suffered by Marie.

A bit to the north, on the east side of 7 Avenue South, is Sheridan Square and the Stonewall National Monument. On Christopher Street, across from the park, is the Stonewall Inn, an important location, but by no means the only one, in the struggle for LGBTQ rights that is far from finished. This is one part of civil rights and it is fitting that there is a memorial in this place.

Just to the north on West 10 Street, is a jazz club called Small’s. At one time, when it was owned by a fascinating, kind character named Mitch Borden, it was a BYOB place where, having paid to get in, one could stay the whole evening and hear excellent jazz by little-known performers. A bit farther north is the famed Village Vanguard, a jazz mecca for generations. It is a triangular space downstairs from the sidewalk, the musicians playing in one apex of the triangle. The bar is on the side of the triangle opposite the stage and it was my preferred place to sit, looking out over the tables and perhaps chatting with the bartender.

I turned north onto Waverly Place and then left (west) on West 11 Street, then right (north) on West 4 Street. An intersection of West 4 and West 11 Streets, one might wonder. Only in New York, I suppose.

Timely sign on West 11 Street.

After lunch at Xi’an Famous Foods at 8 Avenue and West 15 Street (terrific food but the seating seems to have been designed for small children), the walk ended at the subway station at 8 Avenue and West 14 Street. This busy station is home to whimsical bronze sculptures by Tom Otterness, starting at the elevator on the street and continuing throughout the station.

My favorite group of sculptures in the station. Two men are trying to saw away the support column. That great creature of urban myth, the New York sewer alligator, grabs someone for its meal while someone else just looks on. Whimsical and unsettling at the same time.

This was a most enjoyable walk. The southern part of the walk had paving blocks that had to be negotiated with some care. Mere steps from either side of the walk was so much more to see. I wanted to put together a completely accessible walk with a lot to see, and I succeeded. I could have lingered at many places on the walk. You might choose to do so.

Ridgewood, Maspeth, and Two Bridges (Queens and Brooklyn)

WHERE: From Ridgewood, Queens, through Maspeth, Queens, across two bridges to East Williamsburg, Brooklyn

START: Forest Avenue subway station (M train)

FINISH: Grand Street subway station (L train)

DISTANCE: 3.1 miles (5 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl. Map courtesy footpathapp.org.

Route (reading from right to left) and profile (reading from left to right) of this walk.

For this last walk of 2022 I decided to walk across the two Newtown Creek bridges I had not yet crossed on foot (I have biked across both many times), beginning with a walk through the Ridgewood and Maspeth neighborhoods of Queens. The bridges are on Grand Street and Metropolitan Avenue.

The walk started at the elevated Forest Avenue subway station, in a quiet corner of Ridgewood. Ridgewood used to be home to a lot of people of German and Eastern European heritage, augmented in recent years by Hispanic people, people from the Balkans, and people priced out of places such as Williamsburg. A few blocks into the walk I noticed Rosemary’s Playground. From the New York City Parks website:

Rosemary's Playground is named for one of Ridgewood's brightest political leaders, who lived much of her life at 1867 Grove Street. Born in Brooklyn on February 7, 1905, Rosemary R. Gunning (1905-1997) graduated from Richmond Hill High School in Queens in 1922. Soon after she received the L.L.B. from Brooklyn Law School in 1927, she was admitted to the bar in New York State. Rosemary worked for a Manhattan and Long Island law firm during the Great Depression, and then served as an attorney for the Department of the Army from 1942 to 1953. She married Lester Moffett in 1946.

Ms. Gunning entered the New York political scene as a Democrat and later joined the Conservative Party. One year after she attended the 1967 New York Constitutional Convention, Rosemary became the first woman to be elected to the New York State Assembly from Queens. During four two-year terms, her major achievements included bills supporting school decentralization and the creation of the Housing Court.

A bit farther along Fairview Avenue I came upon an old German beer hall that appears to have an outdoor beer garden. I’ll be back. Gottscheer Hall gets its name from the county of Gottschee in present-day Slovenia. An interesting history of Gottschee and the migration of Gottscheers to New York and elsewhere is at https://gottscheerhall.com/history

When I was mapping out this walk I saw that along the way was a little one-block street with the grand name of St. John’s Road. So I had to include it on the walk. If anyone knows how this street got its name, please let me know!

St. John’s Road, looking west from Grove Street.

Holiday display on St. John’s Road.

From there I continued along Woodward Avenue, past Linden Hill Cemetery, founded in 1842. Its hilltop location affords an excellent view of Manhattan in the distance. The evolution of Ridgewood is captured in the diversity of family names on the gravestones. Alas, the wrought iron fence around the cemetery is topped with barbed wire and the entrances to the cemetery are festooned with all sorts of “don’ts.”

Downhill from the cemetery, I turned from Woodward Avenue onto Troutman Street. At the end of Troutman Street, at the intersection of Flushing Avenue and Metropolitan Avenue, is the former warehouse of the H.C. Bohack Company. Bohack was a supermarket chain in Brooklyn, Queens, and Long Island from 1887 to 1977. The first time I saw this, on a bike ride in the area in 2015 (when I took the photo below), I was astonished that this bit of history was extant.

From Troutman Street almost to the end, the walk was ugly. I passed a lot of warehouses, wholesalers of all kinds of things, a big lumber yard, an equally big New York City Transit bus garage, small metalworking firms, and truck terminals. But ugly places like these are vital to the City’s economy. On 54 Street I saw some private houses incongruously placed amid all this, and the former Bushwick Branch of the Long Island Rail Road, which still sees the occasional freight train. It has not seen a passenger train since 1924.

The Maspeth Business Park on Grand Avenue (it becomes Grand Street in Brooklyn, west of the Grand Street Bridge). Look at the signs. All this time I thought Queens met the world at JFK Airport.

Eventually I came to the Grand Street Bridge, a swing span built in 1903. I’ve biked over the bridge and its challenging steel grate roadway many times but had never walked it before. It crosses the most polluted section of one of the most polluted waterways in the United States, Newtown Creek. In the image, note the small wooden shack at mid-span. That was a challenge to shimmy past.

Past the Grand Street Bridge, I passed more of the same until a short detour onto Stewart Avenue to Metropolitan Avenue. Ahead lay the Metropolitan Avenue Bridge, a double-leaf drawbridge that opened in 1933. It crosses the English Kills, a heavily polluted tributary of Newtown Creek. Just east of the bridge was a mural that I couldn’t explain but caught my eye.

Metropolitan Avenue Bridge, looking west.

View of English Kills from the Metropolitan Avenue Bridge.

If you ever walk along the north walkway of the Metropolitan Avenue Bridge (I didn’t), do not attempt to cross the exit to westbound Metropolitan Avenue. There is too much fast-moving traffic.

Continuing along Grand Street, warehouses and light industry dominate the south side of the street, while the north side changes slowly with new restaurants and a film camera business (to which I’ll go back) alongside a long-standing auto repair business. The end of the walk was the Grand Street subway station at the top of a gentle hill. This station is being made accessible, and the elevators and other improvements should be complete in 2023.

Elevator tower under construction to the Manhattan-bound platform of the Grand Street subway station.

I have now walked across all six walkable bridges over Newtown Creek and its tributaries: Pulaski, Borden Avenue, Greenpoint Avenue, Kosciuszko, Metropolitan Avenue, and Grand Street. The two parts of this walk were very different but the common denominator was the utter, unsurprising lack of tourists. There was plenty to see for anyone with eyes wide open, taking it all in at a slow pace. Maybe one day I’ll do a series on one-block streets, starting with St. John’s Road. The portions of the route that I’ve biked in the past - everything from Troutman Street west - I saw differently on two feet than I ever did on two wheels. I passed places to which I will surely return: Gottscheer Hall for beer and wurst, a place on Grand Street that sells dumplings and pork buns by the bag, Brooklyn Film Camera, others. This was a good, low-key way to cap a year of good walks.

Onward! Happy New Year!

More of the Old Croton Aqueduct, and More

WHERE: The Old Croton Aqueduct Trail and the Manhattan College Steps, Bronx

START: McLean Avenue and Lee Avenue, Yonkers (No. 4 Bee-Line bus from Woodlawn subway station, 4 train)

FINISH: West 238 Street and Riverdale Avenue (Bx7 bus to 207 Street subway station, A train - fully accessible)

DISTANCE: 3.1 miles (5 kilometers)

Photographs by Daniel Murphy except as noted. Map courtesy of footpathapp.com.

Route and profile of this walk. Route reads from right to left, profile from left to right.

On this walk I returned to the Old Croton Aqueduct, sections of which I’ve walked and written about before. The aqueduct opened in 1842 and gave New York City, then limited to Manhattan, its first reliable supply of fresh water. On “The Stair Streets of New York City” page, see the posts entitled “The Joker Stairs (West Bronx) and High Bridge (Bronx to Manhattan),” “Back to the High Bridge,” “West Bronx Mix,” and “The Stick It to the Stroke Stair Climb and Gallivant.” This walk included a section of the Old Croton Aqueduct in Van Cortlandt Park and a return to the Manhattan College Steps.

We started out just over the New York City line in Yonkers, where after a short walk from the bus we reached the Old Croton Aqueduct trail. This is a dirt path atop the old aqueduct, going through the woods of Van Cortlandt Park.

Yours Truly where the trail crosses into New York City.

The trail is secluded and quiet except for the sound of distant traffic from the Saw Mill River Parkway and Mosholu Parkway. Along the way there is a large masonry structure called a weir chamber, one of several along the aqueduct. Inside the weir chamber was a gate that could be lowered to close off the downstream section for repairs, the water in the aqueduct being diverted to a nearby stream, in this case Tibbetts Brook.

Weir chamber.

Tibbetts Brook is a small stream that begins its journey in the City of Yonkers and flows south into Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx. The stream cuts through the middle of the parkland into Van Cortlandt Lake, then dips underground beneath Tibbett Avenue, flowing southwest into the Harlem River Ship Canal. In the 18th century, Tibbetts Brook was dammed to create the lake that still exists in the park, and part of the brook was buried underground in 1912.

Tibbetts Brook is a major link in the natural drainage pattern of Van Cortlandt Park, which encompasses a watershed of slightly under 850 acres (344 hectares). Runoff collects in the stream, drains into Van Cortlandt Lake, and eventually empties into the Harlem River by way of a network of underground sewers. Development along the waterway, such as highway construction, often creates new sources of highly concentrated runoff that disrupt the delicate balance of the Harlem River ecosystem, causing erosion and contamination with salt, oil, and roadside debris.

From the Van Cortlandt Park Alliance website:

Tibbetts Brook is added into the sewer system unnecessarily, so environmental activists have been advocating for it to be removed from the sewer system and “daylighted.” Daylighting a body of water is the process of moving the water that has been diverted to an underground pipe above ground, and adding in components to enhance the space.

Green infrastructure is one component of this process, to reduce flooding and mimic how the natural land would deal with water. The goal of daylighting Tibbetts Brook would not only be to decrease the amount of [combined sewage overflows] that enter the Hudson River, but also to benefit the park and surrounding communities. The project will extend an existing greenway, add better access to the area, and will become a new stretch of public park for the community to enjoy.

The trail continues through woodland to a walkway alongside the Major Deegan Expressway (Interstate 87) and an accessible ramp down to the Van Cortlandt Golf Course, the oldest public golf course in the United States.

The Old Croton Aqueduct Trail south of the weir chamber,

The section of the trail alongside the Major Deegan Expressway, crossing Mosholu Parkway.

Monument to Algernon Sydney Sullivan (1826-1887) near the golf course clubhouse. “Jurist - Statesman - Orator. An immaculate life devoted with never failing fidelity to public and private trusts.” According to Wikipedia, Sullivan “was an American lawyer noted for his role in the business law firm Sullivan & Cromwell. … In 1857, Sullivan moved to New York City, and soon took a prominent position as a lawyer and public-spirited citizen. He was retained to defend the officers and crew of the Confederate schooner Savannah, the first vessel to be captured during the Civil War, who were on trial for their lives on the charge of piracy. From 1870 to 1873 Sullivan was assistant district attorney for New York City, and upon leaving that office he formed a partnership with Hermann Kobbe and Ludlow Fowler. In 1875, he was appointed public administrator, during which he instituted many reforms, reducing the charges upon estates administered, and, in spite of pressure, retaining in his service efficient assistants of a political party different from his own. In 1878 the firm of Sullivan, Kobbe & Fowler was dissolved and he formed a partnership with William Nelson Cromwell, under the name of Sullivan & Cromwell, which firm name is still retained by the successors to his business.” Why is this monument in this place? Who knows. Photograph by Michael Cairl.

We left Van Cortlandt Park to walk south on Bailey Avenue, then west on West 238 Street to the Manhattan College Steps. Up the stairs we went, then west and uphill one more block to lunch at the An Beal Bocht Cafe. For me, it was a return to a fine place. The cafe was fairly full with people watching the World Cup quarter-final between England and France. This being an Irish establishment, I don’t think many were cheering for England. A lunch of shepherd’s pie hit the spot on this chilly day.

At the base of the Manhattan College Steps. Left to right: Michael, Dan, Yours Truly. Photograph by Paul Murphy.

Graffiti of encouragement, halfway up the Manhattan College Steps. Photograph by Michael Cairl.

Eating outside at An Beal Bocht Cafe, the crew on this walk: Left to right, Paul, Yours Truly, Joe, Michael, Dan, Andrew. Photograph by the bartender at An Beal Bocht.

This was a good walk on a perfect day for it. It highlighted the history and ecology of this chunk of the Bronx, gave a walk in the woods that one doesn’t usually associate with the Big City, included a return to the Manhattan College Steps (120 steps, handrails too low, risers too high), and I had great company for the walk. The section through the park was just east of a walk along the Putnam Trail, a little bit to the west, that I did exactly a year before. Walks north on the Putnam Trail and Old Croton Aqueduct might be in the future.

New York's Deep South

WHERE: Tottenville, Staten Island

START/FINISH: Tottenville station, Staten Island Railway, fully accessible

DISTANCE: 2.89 miles (4.65 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl except as noted. Map courtesy footpathapp.org.

Map and profile of this route. Read from left to right.

The southernmost place in the state of New York is the Tottenville neighborhood of Staten Island. While it is part of New York City, it looks like a place apart, an old village in a big city, rather like City Island in the Bronx. Tottenville is a quiet, suburban place with plenty of history. It lies across the Arthur Kill from Perth Amboy, New Jersey, to which it was linked by ferry until 1963. Through traffic bypasses Tottenville, going mostly along New York/New Jersey Route 440 by way of the Outerbridge Crossing, just north of Tottenville, to two expressways on the Staten Island side. This helps Tottenville keep its village feel, its apartness. Apartness does not mean a lack of diversity, though, as becomes apparent just by looking and listening.

We started by taking the Staten Island Railway from the St. George Ferry Terminal to the last stop, Tottenville station. The Perth Amboy ferry used to run here. The walk began with a short uphill on Bentley Street. The utility poles along the street were festooned with American flags and there were many old houses with porches.

Perth Amboy, New Jersey, seen from the Tottenville train station.

Bentley Street..

Around the corner on Amboy Road are some even older houses. This one has a medallion that reads “Circa 1814.”

We continued on to Conference House Park and a number of historic houses in the park. From nycparksgov.org:

Conference House Park is a great destination for both park and history buffs. Located at the southernmost point of New York State, this park houses four historic buildings that trace the history of the borough over the course of three centuries. The Conference House, the Biddle House, the Ward House and Rutan-Beckett House all tell of a New York and an America of the past.

The Conference House, a grand stone manor house built in 1680, is named for the unsuccessful Revolutionary War peace conference that was held here on September 11, 1776 between the Americans and the English. Despite their negotiations to end the fighting, no agreement was reached and the Revolutionary War continued for another seven years.

In addition to its historic landmarks and its breathtaking views of the Raritan Bay, the 265-acre park boasts a newly refurbished playground, a Visitors Center, expanded paths and hiking and biking trails. Another great park destination is the “South Pole,” marking the southernmost point of New York State.

The first house we saw, the Biddle House, was built in 1845 by the operator of the Perth Amboy ferry. We walked inside and saw a dance class going on. More information about the house is at https://www.statenisland.guide/explore-feat/i/27681582/biddle-house-conference-house-park. Down a hill that was too steep to navigate safely was the Rutan-Becket House (1848), Read about it at https://theconferencehouse.org/the-historic-houses-of-conference-house-park/the-rutan-becket-house/.

Biddle House.

Continuing on, we saw the Ward House, which looked much older than the other two and is closed to the public.

Ward House.

The intended centerpiece of this walk, the Conference House, was closed for the Thanksgiving holiday. I’ll just have to come back when it is open. From The WPA Guide to New York City (1939):

At the request of Lord Howe, the British admiral, the Continental Congress appointed a delegation of three - Benjamin Franklin (a friend of Lord Howe), John Adams, and Edward Rutledge - to met with him on September 11, 1776. The discussion proved fruitless, for the Americans refused to barter for peace unless the British granted independence to the colonies.

The delegation returned to Perth Amboy aboard Howe’s barge. As the boat entered the wharf Franklin offered some gold and silver coins to the sailors but the commanding officer intervened. “As these people are under the impression that we have not a farthing of hard money in the country,” Franklin later explained to his companions, “I thought I would convince them of their mistake. I knew at the same time that I risked nothing by an offer, which their regulation and discipline would not permit them to accept.” The group then traveled to Philadelphia, where its report was submitted to Congress.

The land on which the house stands was included in a patent of 932 acres granted in 1676 to Christopher Billopp, a British Navy captain who two years earlier had come to America with Governor Andros. In 1687 Thomas Dongan, Andros’ successor, granted the patent and an additional 668 acres to Captain Billopp as the manor of Bentley.

The house, built by Billopp prior to 1688, was for many years the island’s most imposing mansion. The property was inherited by Thomas Farmar, Jr., third son of the captain’s daughter, Anne. Under the terms of the will the heir assumed the name of Thomas Billopp. Christopher, Thomas’ eldest son, became the next proprietor of the estate. A Tory colonel, he frequently entertained British officers, including Lord Howe, and his house was kept under constant surveillance by the Americans entrenched on the New Jersey shores of the near-by Arthur Kill. At the time of the historic meeting redcoats were quartered in the mansion. Colonel Billopp did in 1827.

The house, subsequently used as a factory, fell into neglect. Many efforts were made to restore it, but none was successful until 1925, when the Conference House Association was organized. The real-estate company that had acquired the property deeded the house and an acre of land to the city in 1926; three years later the Municipal Assembly [now the New York City Council] made the association custodian of the building.

From Wikipedia:

Archaeological evidence, including shell middens and digs conducted by The American Museum of Natural History in 1895, have shown that the Raritan band of the Lenape camped in the area and used the location as a burial ground. Known as Burial Ridge, it is the largest pre-European site in New York City.

Legend holds that sovereignty of Staten Island was determined by Capt. Billopp's skill in circling it in one day, earning it for New York rather than to New Jersey. This has since been disproven and is in fact a myth.

Conference House. Photograph courtesy urbanarchive.org.

Across the street from Conference House Park is this house that caught my eye.

Near Conference House there is a viewing platform affording a view of Raritan Bay, South Amboy, the mouth of the Raritan River, and Perth Amboy. On the opposite side of Raritan Bay are New Jersey’s Atlantic Highlands.

A good footpath winds through the woods of Conference House Park, past white plastic tubes protecting saplings, and over a small bridge where people were feeding ducks and geese.

Upon leaving the park we walked the length of Main Street, which starts out as single-family residential, up a decent but not challenging hill, going through Tottenville’s old retail heart, past the post office and police station, and ending at the train station.

Apartment house on Main Street in central Tottenville that looks as though it would be more at home in the Bronx, Brooklyn, or Queens.

Old sign at a former appliance store, Main Street, Tottenville.

123d Precinct (1924), NYPD, Main Street, Tottenville. Photograph courtesy urbanarchive.org. From the AIA Guide to New York City, Fifth Edition (2010): “Italian Renaissance Revival, somewhat out of context with the small-scale village it inhabits, but elegantly conceived.”

This was a fine walk and Tottenville is well worth a return visit; the Conference House awaits and there are other architectural gems to explore. In terms of distance and character, Tottenville is as far from the crowded, bustling city as one can get while remaining in the city limits. The walk was accessible, but noting the uphill on Bentley Street and an uphill on Main Street where the grade exceeds 3 percent, and the crushed gravel surface of most of the path through Conference House Park. Sidewalks aren’t always continuous but there isn’t much motorized traffic; still, look sharp as you go along.

Newtown Creek Walk #1

WHERE: Pulaski Bridge, Greenpoint Avenue Bridge, and Borden Avenue Bridge

START/FINISH: 11 Street and Jackson Avenue, Long Island City, Queens

DISTANCE: 3.1 miles (5 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl except as noted.

Route of this walk, courtesy footpathapp.org.

On this brisk, nearly cloudless November day ten people joined me on a walk over three Newtown Creek bridges. Newtown Creek forms part of the boundary between Brooklyn and Queens, and is one of the most polluted waterways in the United States. The banks of Newtown Creek have long been mostly industrial, but close to the East River that has been changing with the construction of high-rise apartment buildings. None of the areas we walked through are tourist territory.

We started in Long Island City, Queens, near the north end of the Pulaski Bridge. This double-leaf lift bridge opened in 1955 to replace a low-level lift bridge, the Vernon Bridge, nearby. The Vernon Bridge carried traffic between Vernon Boulevard in Long Island City and Manhattan Avenue in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. The Pulaski Bridge used to have bicyclists, runners, and pedestrians competing for space on the footpath. In recent years one of the Brooklyn-bound traffic lanes was converted to a bicycle lane, a much more satisfactory solution given the volume of bicycle and foot traffic using the bridge.

Pulaski Bridge, looking from the west. Image courtesy bridgehunter.com.

Hunterspoint (Vernon) Bridge, circa 1905. Image courtesy atlasobscura.com.

Leaving the bridge, we went west on Eagle Street one block to Manhattan Avenue, then south to Greenpoint Avenue. Greenpoint is an old Polish neighborhood, and while one still sees a lot of Polish shop signs and hears Polish being spoken, things are changing. Newcomers are moving in despite the lack of direct subway service to Manhattan: the G train has two stations on Manhattan Avenue but runs only between Brooklyn and Queens. We turned east on Greenpoint Avenue after some in our group stopped at a Polish bakery for bread and doughnuts. Passing the fire house on Greenpoint Avenue, we met John, an FDNY fire fighter who ran the New York City Marathon with Michael from our group. A totally unexpected, serendipitous moment, of a piece with the encounters I often have on these walks. Accordinig to Michael, John ran the Marathon wearing Crocs.

Fire fighter/EMT John flanked by walkers Michael (left), Kevin, and Yours Truly. Photograph by Tess Tokash.

From there, we walked past the architecturally fascinating Newtown Creek Wastewater Treatment Plant, the largest in New York City, to the Greenpoint Avenue Bridge. The most striking feature of this plant is eight huge egg-shaped structures that house the plant's sludge digesters. The digesters use a process called anaerobic digestion to transform the sewage plant sludge byproduct into a form which can be used as fertilizer. The plant gives monthly public tours of the digester eggs, for which reservations are required. The plant's design has won awards from the American Institute of Architects, the Society of American Registered Architects, and from the Art Commission of the City of New York (now known as the NYC Design Commission).

Sludge digesters, Newtown Creek Wastewater Treatment Plant.

The Greenpoint Avenue Bridge, a double-leaf lift span, opened in 1987 and is the sixth bridge at this location, crossing Newtown Creek from Brooklyn to Queens. From Wikipedia: In the 1850s, Neziah Bliss built the first drawbridge, which was called the Blissville Bridge. It was followed by three other bridges before being replaced by a new bridge in March 1900. A new bridge opened in 1929 and after suffering from mechanical problems it was replaced by the current structure in 1987.

View from the Greenpoint Avenue Bridge. Kosciuszko Bridge is in the left background.

Eight of the eleven walking up the Greenpoint Avenue Bridge. Photograph by Jennifer Tokash.

The approach to the footpath on the west side of the bridge, at both ends of the bridge, is not only not accessible but is hazardous. At the Queens side the condition of the footpath approach was such that I considered it safer to step into the bike lane and continue walking.

Queens end, west footpath, Greenpoint Avenue Bridge.

From the Greenpoint Avenue Bridge we walked through an industrial area, past the Silvercup East Studios, to Borden Avenue and the third bridge of the day. The Borden Avenue Bridge crosses Dutch Kills, a branch of Newtown Creek. This bridge was completed in 1908 and is a retractable bridge. When it opens it slides on rails into a berth, rather than lifting or swinging. It is one of four such bridges remaining in the United States, two being in New York City. (The other is the Carroll Street Bridge in Brooklyn, which I’ll cover on a future walk.)

Borden Avenue Bridge, showing the rails on which the span retracts.

Control house, Borden Avenue Bridge.

We finished the walk a few blocks past the Borden Avenue Bridge with lunch at Jora, a wonderful Peruvian restaurant in Long Island City. This walk had it all: a mostly accessible route with some challenges (note to the Department of Transportation: fix these!), a great group to walk with (including one of my occupational therapists from Brooklyn Methodist Hospital and some of her students from Pace University, a high school classmate of mine, a survivor of Guillain-Barre Syndrome who runs marathons, and others), a serendipitous encounter in front of a fire house, and a great lunch, all on a bright, chilly day. This was a hugely satisfying walk that I’m glad I could do with others. Onward!

Take a Walk!

WHERE: Anywhere!

99% INVISIBLE is one of my favorite podcasts. It focuses mostly on the built environment. This episode focuses on the joys of walking, something I’ve always found appealing. Give it a listen.

https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/99-invisible/id394775318?i=1000519252479

Two Bridges (Manhattan and the Bronx)

WHERE: The 145 Street Bridge and the Macombs Dam Bridge over the Harlem River

START: 145 Street subway station (3 train)

FINISH: 168 Street subway station (A and C trains, fully accessible; 1 train, not accessible)

DISTANCE: 3.26 miles (5.25 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl except where noted. Map courtesy footpathapp.com.

Route of this walk, reading bottom to top, and profile of this walk, reading left to right.

On this unseasonably warm (73F/22C) November day I continued my new series of walking the walkable bridges in New York City by crossing two that span the Harlem River. The Harlem River, like the East River, isn’t really a river with a source and a mouth. These are estuaries, in a sense branches of the Hudson River but also part of Long Island Sound. I started the walk at the subway station at West 145 Street and Lenox Avenue. This station is an oddity in the subway system. It opened in late 1904 as the northernmost station on the Lenox Avenue line, which it was until 1968. A few blocks to the south the tunnel that carries the 2 train diverges from the Lenox Avenue line and continues to the Bronx. Just north of the 145 Street station the line rises to the surface and continues west past Lenox Yard to the 148 Street station at Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard. Lenox Yard was for decades the site of the principal maintenance and repair shops of the Interborough Rapid Transit Company. The repair shops closed in the 1960s and an apartment complex was built over the subway yards. The New York City Transit Authority wanted to close the 145 Street station but community pressure has kept it open.

What makes this station an oddity? One cannot enter the station on the uptown side; the stairs on the uptown side are exit-only. Like most of the original subway stations, the platforms were only long enough for five-car trains. After World War II those stations that remained open had their platforms lengthened to accommodate longer trains, except the Grand Central and Times Square shuttle stations (which have shorter trains to this day), the original South Ferry station (now out of service), and the 145 Street station. One has to be in one of the first five cars to exit the station. 145 Street station got a facelift in recent years through the MTA’s Enhanced Station Initiative; the original mosaics and terra cotta cartouches are complemented by new art work.

Around the corner from the subway entrance is the approach to the 145 Street Bridge, which links West 145 Street in Manhattan and West 149 Street in the Bronx. This is a swing bridge. The bridge opened in 1905 but the swing span was replaced in 2006 with a look-alike span that was floated into place.

145 Street Bridge viewed from the north. Photo by Arnoldius - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24602137

The bridge has respectable pedestrian traffic: many people seemed to be going to or from the shopping mall built on the site of the Bronx Terminal Market. The city built the market in 1935 to house wholesale dealers in perishable foods. Eventually all the wholesalers here and at other markets moved to the Hunts Point Terminal Market in the south Bronx. One small bit of the Bronx Terminal Market remains at West 149 Street. I love that letteriing at the top of the building!

Original entrance, Mott Avenue station, looking west on East 149 Street. Photo (1940) from the New-York Historical Society.

I walked east (uphill) on 149 Street to the Grand Concourse and another subway story. When the subway opened to the Bronx in 1905 there was a station here called Mott Avenue, the original name of what is now the southern end of the Concourse. Owing to the underwater tunnel and the sharp rise in the land, this station was (and is) a deep one. Until the station was enlarged in 1918 with a second line on an upper level, the only access to the station was by elevators from a small station house at the southwest corner of this intersection. This entrance was closed many years ago but is getting a revival as part of a project to make the whole station complex fully compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act. The station house is being rebuilt for elevator access from the street, and the original terra cotta station tablet will be preserved.

149 Street - Grand Concourse station: rendering of rebuilt station house (top) and cutaway of station complex as rebuilt. Design and images by STV Incorporated.

Remains of the old station house, at the same location where the new one is being built. Look closely for the “Mott Avenue Station” tablet that will be preserved on the new station house.

This is a busy area, with Hostos Community College on the south side of 149 Street and on both sides of the Concourse, the Bronx General Post Office at the northeast corner, Lincoln Hospital two blocks east, and Cardinal Hayes High School two blocks north. I walked north on the Concourse past Franz Sigel Park and the Bronx County Court House, on the Concourse between East 158 and East 161 Streets, a masterpiece of municipal architecture from the 1930s.

Bronx County Court House.

I turned west on 161 Street, a wide and busy thoroughfare, past small businesses that depend on traffic from the Court House and Yankee Stadium, past the elevated subway station at River Avenue, past Yankee Stadium and the baseball fields built - after years of delay - on the site of the first Yankee Stadium, to the Macombs Dam Bridge. Built in 1895, this is actually two bridges: a truss span over the Metro North Railroad tracks and a swing span over the Harlem River.

Pattern from the original balustrade on the Macombs Dam Bridge walkway.

From Wikipedia:

The first bridge at the site was constructed in 1814 as a true dam called Macombs Dam. Because of complaints about the dam's impact on the Harlem River's navigability, the dam was demolished in 1858 and replaced three years later with a wooden swing bridge called the Central Bridge, which required frequent maintenance. The current steel span was built between 1892 and 1895, while the 155th Street Viaduct was built from 1890 to 1893; both were designed by Alfred Pancoast Boller. The Macombs Dam Bridge is the third-oldest major bridge still operating in New York City, and along with the 155th Street Viaduct, was designated a New York City Landmark in 1992.

Macombs Dam Bridge from 155 Street Viaduct, 1899. Photo Museum of the City of New York via urbanarchive.org.

The pedestrian approach to the Bronx end of the bridge is not straightforward; there are curb cuts but one has to look for them. There is a lot of traffic exiting the bridge to the southbound Major Deegan Expressway (Interstate 87) and I had to be even more alert than usual there. At the Manhattan end of the bridge I could not proceed directly to the 155 Street Viaduct, but had to go south on a less-than-ideal sidewalk to a crosswalk at West 153 Street, then cross Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. Boulevard, then double back to the viaduct. The pedestrian passage from the Bronx to the viaduct can be made straightforward and safe, not so motorist-centered. Department of Transportation, please do it.

The 155 Street Viaduct starts at the Macombs Dam Bridge on the east, then ascends to West 155 Street at St. Nicholas Place, the Harlem River Driveway, and Edgecombe Avenue. The ascent of the viaduct is not particularly steep but it is long, and the climb was a good workout. Below the viaduct is Frederick Douglass Boulevard and to the north is the site of the Polo Grounds. See my post “The One-Fifties (Upper Manhattan)” on “The Stair Streets of New York City” page for a description of the area and the long flight of stairs going from West 155 Street up to the viaduct.

Once I got to the top of the viaduct, I turned north on Edgecombe Avenue, climbing past the John T. Brush Stairway, the Paul Robeson house, and the Morris-Jumel Mansion, all of which featured in the “Harlem and Heights History Walk (Manhattan)” on the “Other Walks Around Town” page. Before heading to the subway and home, I stopped for a tasty lunch at a hole-in-the-wall Singaporean noodle house, Native Noodles, on a nondescript block of Amsterdam Avenue. The restaurant has two steps up to the door and no handrail, but they very kindly set me up with a table and chair outside. I’ll be back.

This was a good workout of a walk with plenty of interesting things along the way and a big smile and encouragement from a passerby on the 155 Street Viaduct, all on a beautiful day. It was a good way ro mark the fourth anniversary (plus one day) of my stroke. And there are many more walkable bridges, returns to stair streets, and other walks to come.

Kosciuszko Bridge (Brooklyn to Queens)

START: Nassau Avenue subway station (G train)

FINISH: 52 Street subway station (7 train)

DISTANCE: 3.1 miles (5 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl except where noted.. Map courtesy footpathapp.com.

When I was growing up I heard the name of this bridge pronounced “koski-osko.” Proper pronunciation is something closer to “ko-SHOO-sko.” With that out of the way, this is the second Kosciuszko Bridge. The current bridge is a dual suspension span, the one carrying traffic to Queens opening in 2017 and the one carrying traffic to Brooklyn, plus a wide pedestrian and bike path, opening in 2019. The bridge carries the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway (Interstate 278) over Newtown Creek, a body of water so polluted that it is a Superfund site.

The first bridge opened in 1939 as the Meeker Avenue Bridge and was renamed a year later. It was an awful, ugly old span. Its daily traffic volume was well in excess of what it was designed for. The bridge’s clearance above Newtown Creek was much greater than it needed to be. The steep grades at either end of the span and the lack of shoulders made a quick transit of the bridge a rare occurrence indeed.

The first Kosciuszko Bridge. Image courtesy historicbridges.org.

I started this walk in the Greenpoint neighborhood of Brooklyn. It has long been an industrial area and has long had a large Polish community. Some street scenes follow.

Polish pharmacy on Nassau Avenue.

Polish restaurant on Nassau Avenue.

This might not be a Polish establishment but it has a great old sign, probably from the 1940s, above the storefront. On Nassau Avenue.

This street sign, at the intersection of Nassau Avenue and Monitor Street, recalls the fact that the U.S. Navy’s first ironclad warship, the Monitor, was built in 1861 in a shipyard in Greenpoint.

Eventually I got to the Brooklyn end of the bridge, where there is a nice little plaza and a monument to the bridge’s namesake, Tadeusz Kosciuszko.

At the Brooklyn end of the bridge.

Beneath the bridge on the Brooklyn side are scrapyards and light industry. At the Queens end of the bridge are a yard for construction cranes on one side and a section of the huge Calvary Cemetery on the other. The bridge does offer quite a view of Manhattan.

Brooklyn on the left, Newtown Creek in the middle, Queens on the right, Manhattan in the distance.

One of the sections of Calvary Cemetery, from the Queens end of the bridge.

A very nice safety measure at the Queens end of the bike and pedestrian path. A similar measure was installed on the sidewalks at grade crossings of Utah Transit Authority’s TRAX light rail extensions, to make people more aware of a grade crossing where trains would be running.

Skate park at the Queens end of the bridge.

From the Queens end of the bridge there is a serpentine path leading past the Long Island Expressway (Interstate 495) to the Sunnyside neighborhood. The path is narrower than that on the bridge but it is in excellent condition. Sunnyside is a diversifying residential neighborhood built after what is now the number 7 subway (Flushing line) opened in 1917. Greenpoint Avenue cuts diagonally across the street grid and is a busy commercial street. It led me to a nice Filipino restaurant, Kabayan, for lunch. At another table a group of six was having a feast of all kinds of meat and seafood with clumps of rice, all spread out on banana leaves. It made me want to go back with a bunch of people, having reserved this feast ahead of time.

On my way to journey’s end, the shabby 52 Street subway station, I saw the God is Love Parking Lot.

This was an excellent walk on a nice, cool day. The Kosciuszko Bridge was easy to get to and a delight to walk. There was good walking at either end of the bridge and a tasty lunch at the end. I’ve added crossing the walkable bridges of New York City to my travels and will keep it up. The bridges across Newtown Creek and its tributary, Dutch Kills, will take up two more walks, and there are plenty more around the city. For more information about Newtown Creek and its bridges, past and present (except for the new Kosciuszko Bridge) go to Kevin Walsh’s excellent post at NEWTOWN CREEK - Forgotten New York (forgotten-ny.com).

Route of this walk.

The 59 Street Bridge (Queens to Manhattan)

START: Queensboro Plaza subway station (7, N, W trains)

FINISH: Lexington Avenue - 63 Street subway station (F, Q trains), fully accessible

DISTANCE: 1.8 miles (2.9 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl

Route of this walk, reading from right to left.

This cloudless, cool Saturday was perfect for a good walk. I’ve biked across the 59 Street Bridge quite a few times and driven across it many times, but until today I had never walked across it.

The map above calls this the Ed Koch Queensboro Bridge. Early plans called it the Blackwell’s Island Bridge, for the original name of the slender island in the East River that the bridge goes above. When the bridge opened in 1909 it was called the Queensboro Bridge. Blackwell’s Island was renamed Welfare Island in 1921, on account of the municipal hospitals on the island, and was again renamed Roosevelt Island in the 1970s when it was redeveloped as a new town in the city. In 2011 the bridge was renamed the Ed Koch Queensboro Bridge, after the former three-term mayor of New York (1978 - 1990), who had nothing to do with the bridge’s construction. It’s odd that we rename public works for dead politicians. Hardly anyone calls the bridge anything but the 59 Street Bridge; its Manhattan terminus is at Second Avenue between East 59 and East 60 Streets. Renaming things is an uncertain thing in this city; sometimes the new name sticks but often it is ignored.

But I digress. The walk began at the Queensboro Plaza subway station, soon (not soon enough) to be made accessible, with an elevator on either side of Queens Plaza, a wide, car-choked approach to the bridge with the massive elevated subway structure in the middle. The bridge’s bike and pedestrian path begins a block from the subway. It’s a long, gentle ascent to the summit, just short of Roosevelt Island, and once the bridge crosses York Avenue in Manhattan the descent is steep. I have to admit I was thinking of Simon and Garfunkel’s “Fifty-Ninth Street Bridge Song” on this walk, even though the song doesn’t mention or allude to the bridge once.

The bridge on the Queens side, with the upper level and lower level roadways on the left and the elevated subway structure on the right.

The bridge approaching Roosevelt Island.

Looking north from the bridge, with Roosevelt Island on the left and Queens on the right. Dominating the Queens shoreline is Consolidated Edison’s Ravenswood generating station.

Detail of the art work in the east mezzanine of the Lexington Avenue - 63 Street subway station, a street scene of when elevated railways rumbled over both Second and Third Avenues in Manhattan. The former was demolished in 1940 and 1942, the Manhattan portion of the latter in 1955.

The steel work of the bridge is massive. It and the Williamsburg Bridge, which opened in 1903, seem to suggest the whole output of the Industrial Revolution. When the bridge was being built, some thought it would collapse of its own weight. It hasn’t; indeed, it has proved to be quite adaptable. It once carried two tracks of the Second Avenue Elevated and a streetcar line. It used to have an elevator going from a streetcar stop at mid-span down to Welfare Island. Now it carries motor vehicles on the upper level, the inner roadway of the lower level, and the south outer roadway. The north outer roadway is given over to pedestrians and bicycles, and there were a lot of both on this day, including motorized bikes. I and others would like to see the south outer roadway given over to pedestrians or bicycles as well, to accommodate the volume of traffic and ensure safety.

This was an easy and fun walk, taking me 44 minutes to go from one end of the bridge to the other, including a couple of brief stops for photos.

“Life I love you, all is groovy.” https://open.spotify.com/track/0dzbfio3qTYG9uk40SJNcr?si=383b2292979649f3

Back to Manhattanville, then to Grant's Tomb and Beyond (Manhattan)

WHERE: Manhattanville, Grant’s Tomb, Columbia University

START: 125 Street subway station (A, B, C, D trains; fully accessible)

FINISH: Cathedral Parkway - 110 Street subway station (1 train)

DISTANCE: 2.2 miles (3.5 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl.

Route of this walk, reading from right to left. Map courtesy footpathapp.com.

This last Saturday of Summer 2022 was perfect for this walk: pleasantly warm and not humid. The first part of this walk was a return to the Manhattanville neighborhood in the valley between Morningside Heights to the south and West Harlem to the north. I described walking through Manhattanville in the post entitled “Four Stair Streets and a Tunnel Street (Manhattan)” on “The Stair Streets of New York City” page. Although this first part of the walk was a return visit, there were still some things at and around St. Mary’s Church of Manhattanville, on West 126 Street.

A bit of old Europe in the facade of a building across the street from St. Mary’s Church.

Profile of the climb up to Grant’s Tomb, courtesy Google Maps.

From there my friend Matt Summers and I walked for a block on Old Broadway them west on West 125 Street, past the impressive steel arch span, called the Manhattan Valley Viaduct, carrying the subway (1 train) over the street here, to Riverside Drive. From here we climbed the steep hill up to the General Grant National Memorial, which everybody calls Grant’s Tomb.

From the National Park Service page about the General Grant National Memorial:

Approximately 90,000 people from around the world donated over $600,000 towards the construction of Grant's Tomb. This was the largest public fundraising effort ever at that time. Designed by architect John Duncan, the granite and marble structure was completed in 1897 and remains the largest mausoleum in North America. Over one million people attended the parade and dedication ceremony of Grant's Tomb on April 27, 1897.”

Grant’s Tomb fronts on a large, tree-shaded forecourt and is a commanding presence on Riverside Drive and from the Hudson River Greenway and Henry Hudson Parkway. Above the entrance is the "epitaph “Let Us Have Peace.” No bombast about Grant’s military campaigns, just Let Us Have Peace.

The mausoleum interior had not yet opened for the day when we got there, so we could not see the sarcophagi of Ulysses S. Grant and his wife, Julia Dent Grant.

For more information about Grant’s Tomb go to https://www.nps.gov/gegr/index.htm.

Across Riverside Drive from Grant’s Tomb is International House, which provides housing for postgraduate students from around the world who attend Columbia and other universities. Read about it at https://www.ihouse-nyc.org/. Directly south of “I-House” is a pleasant park, then The Riverside Church. Riverside was conceived, and the construction paid for, by John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Rockefeller was a Baptist but Riverside has always been non-denominational. From the church’s website, https://www.trcnyc.org/:

The Riverside Church is situated at one of the highest points of New York City, overlooking the Hudson River and 122nd Street, covering two city blocks. Construction began in 1927 with the first service held on October 5, 1930. The Nave seats nearly 2,000 worshipers. The 20-floor tower, rising to a height of 392 feet, is the tallest church in the U.S. and the second tallest in the Western Hemisphere. It contains offices, meeting rooms, and the 74-bell Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial Carillon. The carillon’s 20-ton bourdon bell is one of the largest tuned bells in the world. The smallest bell in our carillon weighs 10 pounds.

Inside the Nave worship sanctuary, the strivings and aspirations of humanity shine through exquisitely detailed carvings, engravings, stained glass, and other iconography, a tribute to the artists, craftsmen, and architects and their dedication to the glory of God. The Labyrinth on the floor of the chancel has been adapted from the maze at Chartres, one of the few such medieval designs in existence.

The pulpit has welcomed speakers from far and near: The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., preached his famous anti-Vietnam War sermon, “Beyond Vietnam,” from this pulpit. Nelson Mandela addressed the nation during an interfaith celebration welcoming him to America. Marian Wright-Edelman of the Children’s Defense Fund spoke about the need to provide quality healthcare to all children; and the well-known Dr. Tony Campolo delivered a sermon concerning affluence in America.

Across West 120 Street from The Riverside Church is The Interchurch Center, a bland building that opened in 1960 and houses offices of many church-related organizations. Across Claremont Avenue from The Riverside Church is the neo-Gothic Union Theological Seminary, and across West 120 Street from it is Barnard College. Both institutions are independent of, but affiliated with, Columbia University, as is Teachers College, across Broadway from Union.

From West 120 Street, just east of Broadway, we climbed a stairway up to the main campus of Columbia University, then approximately diagonally to the gate at West 116 Street and Amsterdam Avenue.

Map of the Columbia campus and environs, from the Columbia University website.

Columbia University was founded in 1754 as King’s College and its first home was on Chambers Street in lower Manhattan. Columbia is one of nine colonial-era colleges, the others being Harvard, Dartmouth, Brown, Yale, Rutgers, Princeton, Penn, and William and Mary. After the Revolution King’s College became Columbia College, and in the 1850s moved to Madison Avenue between East 49 and East 50 Streets. In the 1890s Columbia was reorganized as Columbia University and moved uptown to the site of the Bloomingdale Insane Asylum, which is where the main (Morningside) campus is today. One of the asylum buildings remains and it is in use today as Buell Hall. The master plan for the campus, by the architectural firm of McKim, Mead and White, was never fully realized but a number of the buildings they designed remain, especially the campus’ focal point, Low Memorial Library. I’ll do a separate page about the Columbia campus at some point and won’t dwell here on individual buildings except one, the magnificent St. Paul’s Chapel (1904). This is used for campus religious services and I have been to one wedding there. The photographs below speak for themselves.

From the University’s website:

St. Paul’s Chapel, designed by I. N. Phelps Stokes, is a 2020 winner of the prestigious Lucy G. Moses Preservation Award from New York Landmarks Conservancy. Awarded annually, the Lucy G. Moses Preservation Awards are the Conservancy’s highest honors for excellence in preservation and pay homage to the architects, building owners, and architectural manufacturers whose outstanding work in preservation protects the city’s unique architectural heritage.

As one of the first buildings to be landmarked in New York, St. Paul’s Chapel is cherished for its rich history and welcoming milieu. The nondenominational chapel hosts approximately 600 religious services every year beneath its 91-foot-tall tiled vault and 16 stained glass windows.

On the remainder of the walk we passed by the Columbia Law School, a former gate house for the Old Croton Aqueduct at West 113 Street and Amsterdam Avenue, and the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine. There will be more walks in, and more posts about, this area.

Why Do I Do This?

My stock answer to this question is “for fun and physical therapy.” Yes, these walkabouts and stair street climbs are good physical therapy. It’s almost four years since my stroke and I cannot stop pushing myself. (Look for a podcast of this blog, coming soon). Going to places where tourists, and many city residents for that matter, don’t go, seeing interesting things and encountering kind strangers, all this is a joy. Having people walk with me makes things even better.

So I don’t do this just for fun and physical therapy. There is spiritual therapy at work too. These walks and the encounters I have along them are energizing.

I am prompted to write this after reading a column in today’s New York Times that says all this more eloquently than I can. Read it at

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/15/opinion/walking-mindfulness-benefits.html?smid=nytcore-ios-share&referringSource=articleShare.

Walk with me, in person if you can, in spirit otherwise. Get out on your feet or in your wheelchair and enjoy. Look up, down, around, and away from your electronic device.

Staten Island Ramble #1

WHERE: Just west of the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge, Staten Island

START: Grasmere station, Staten Island Railway

FINISH: Bay Street and Hylan Boulevard, then S51 bus to St. George Ferry Terminal

DISTANCE: 2.4 miles (3.9 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl and Jordan Centeno as noted. Maps courtesy of Google Maps.

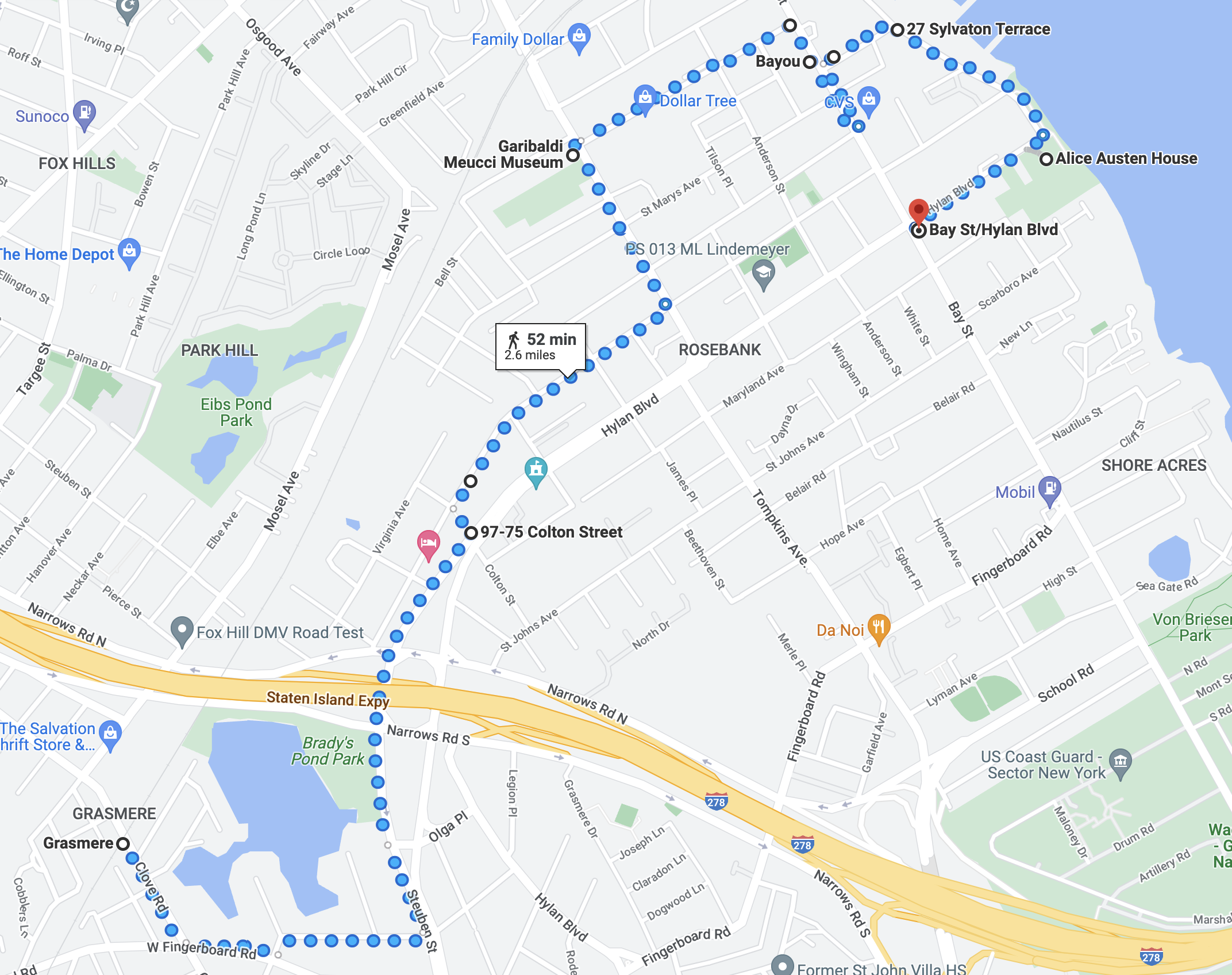

Route of this walk, reading from left to right.

The impetus for this walk was tackling my first stair street on Staten Island, Colton Street in the Rosebank neighborhood. See the post “Colton Street (Staten Island) on The Stair Streets of New York City page. But I was also able to visit two small museums in the area: the Garibaldi-Meucci Museum and the Alice Austen House. My friends Jordan Centeno and Matt Summers joined me on the walk.

We started by taking the Staten Island Railway from the St. George Ferry Terminal to Grasmere station. Grasmere is a quiet suburban neighborhood with sidewalks that are not always wide or even continuous. It reminded me of some of the leafier neighborhoods of eastern Queens.

Grasmere street scene: Windermere Road. Photograph by Michael Cairl.

From Grasmere station it was a more or less steady (but not steep) climb to past the Staten Island Expressway (Interstate 278), then a slight downhill to the Colton Street stairs. We descended the stairs to Clifton Avenue, then through a residential area to the commercial strip of Tompkins Avenue, then to the Garibaldi-Meucci Museum.

Why are there three crucifixes iin the parking lot of St. Joseph’s School? To let wayward whelps know the fate that might befall them if they fell afoul of one of their teachers? Photograph by Michael Cairl.

The Garibaldi-Meucci Museum on Tompkins Avenue. Photograph by Michael Cairl.

Michael and Matt goofing it up at the fence in front of the museum, before realizing the entrance was on Chestnut Avenue. Photograph by Jordan Centeno.

Historical marker outside the Garibaldi-Meucci Museum. Photograph by Michael Cairl.

Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807 - 1882) was a leading figure in the creation of a unified Italy from a collection of kingdoms and the Papal States. Unification was completed in 1870 when the Pope lost control of Rome and its surrounding region of Lazio. As a young adult Garibaldi entered the merchant marine and led rebellions in Brazil and Uruguay before returning to Italy to participate in the revolutions of 1848. He escaped with his life and sailed to New York to buy a merchant ship. This attempt failed and he moved in with his friend Antonio Meucci (1808 - 1889) on Staten Island, staying for several months in 1850 - 1851. Meucci was an inventor who deserves more fame than he got. Garibaldi returned to Italy and led an army of revolutionaries from Sicily through southern Italy.

The museum was Meucci’s house. It is well worth the $10 price of admission. There are numerous pictures and artifacts, and the docent gave an excellent discussion of both Garibaldi and Meucci. Find out more at https://www.garibaldimeuccimuseum.com/ but go visit. There is far more to learn about both men than can be told here.

A few minutes’ walk from the Garibaldi-Meucci Museum, on Bay Street, is Bayou Restaurant, chock-full of New Orleans stuff. They served us a delicious lunch. I had not been there in almost 20 years, when I was the project manager for the installation of a new signal system on the Staten Island Railway. I was glad they’re still alive, kicking, and serving good food. From there we walked down to the waterfront and on to the Alice Austen House.

Staten Island used to have a busy working waterfront, with shipbuilding and ship repair on the North Shore - some of which still exists - and docks and warehousing along the Narrows. When the U.S. Navy’s four battleships were reactivated in the 1980s, one of them, the Iowa, was based at Stapleton, not far from where we were. Some of the structures on the waterfront are active and some are derelict.

Scene at Sylvaton Terrace and Edgewater Street. Photograph by Michael Cairl.

Walking south on Edgewater Street toward the Alice Austen House, we came upon a waterfront promenade named for a local soldier killed in the Vietnam War, Matthew Buono, and sweeping views of New York Harbor.

Looking from the Matthew Buono memorial toward Brooklyn (top) and the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge (bottom). Photographs by Michael Cairl.

Alice Austen (1866 - 1952) was a photographer and native Staten Islander, not just a pioneering female photographer but a pioneering photographer and pioneering woman. Her home, Clear Comfort, was built in 1690 as a one-room Dutch farmhouse. In 1844 it was purchased by John Haggerty Austen, Alice Austen’s grandfather. It sits upon a slight, well-shaded rise above the Narrows, a beautiful spot now to visit and once to have lived. Austen photographed streetscapes, landscapes, scenes of the harbor, and ordinary working people. One can draw a line from her work to that of later photographers such as Berenice Abbott (1898 - 1991) and Helen Leavitt (1913 - 2009). To this longtime amateur photographer, Austen’s eye and sensitivity were remarkable. I could have spent hours going through the library of her prints, and I will go back specifically to do so.

Parlor in the 1844 addition to the house. Photograph by Michael Cairl.

Images of the Quarantine Station on Hoffman and Swinburne Islands, man-made islands from the 19th Century to seaward of the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge. Photograph by Michael Cairl.

About Austen, from the website https://aliceausten.org:

Austen was independently wealthy for most of her life and has widely been considered an amateur photographer because she did not make her living from photography. However, in addition to completing a paid assignment documenting the people and conditions of immigrant quarantine stations in New York during the 1890s, Austen copyrighted, exhibited and published her work.

Alice Austen’s life and relationships with other women are crucial to an understanding of her work. Until very recently many interpretations of Austen’s work overlooked her intimate relationships. What is especially significant about Austen’s photographs is that they provide rare documentation of intimate relationships between Victorian women. Her non-traditional lifestyle and that of her friends, although intended for private viewing, is the subject of some of her most critically acclaimed photographs. Austen would spend 56 years in a devoted loving relationship with Gertrude Tate, 30 years of which were spent living together in her home which is now the site of the Alice Austen House Museum and a nationally designated site of LGBTQ history.

Austen’s wealth was lost in the stock market crash of 1929 and she and Tate were finally evicted from their beloved home in 1945. Tate and Austen were separated by family rejection of their relationship and poverty. Austen was moved to the Staten Island Farm Colony where Tate would visit her weekly. In 1951 Austen’s photographs were rediscovered by historian Oliver Jensen and money was raised by the publication of her photographs to place Austen in private nursing home care. On June 9, 1952 Austen passed away. The final wishes of Austen and Tate to be buried together were denied by their families.

One of the images above is about the quarantine station on Hoffman and Swinburne Islands. A quick sidebar on these, from The Other Islands of New York City: A History and Guide, Second Edition by Sharon Seitz and Stuart Miller (The Countryman Press, 2001):

Staten Islanders had had enough. In 1858, after more than fifty years as New York’s dumping ground for people with deadly, contagious diseases - yellow fever, typhus, cholera, and smallpox - infuriated mobs burned the New York Quarantine Hospital to the ground. In the face of this unsurpassed expression of NIMBY-ism, the government was forced to create two artificial islands, Hoffman and Swinburne, to house the ill.

These islands, to seaward of the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge, are now part of the Gateway National Recreation Area and are home to migratory birds. For years in the 1970s, the Cunard liner Caronia was abandoned, at anchor off Hoffman Island, a ghostly presence.

Profile of this walk, readiing from left to right.

This walk was yet more proof of the fascinating things to be found in this city when one ventures beyond the well-trod tourist trail. It was a good walk with fascinating places visited, a good stair street, a fine lunch, all with good company. Onward!

Bayonne Bridge

WHERE: The Bayonne Bridge, from Staten Island, New York to Bayonne, New Jersey.

START: Innis Street and St. Joseph Avenue, via S46 bus from St. George Ferry Terminal.

FINISH: 8 Street station, Hudson-Bergen Light Rail (fully accessible)

DISTANCE: 2.3 miles (3.7 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl. Map courtesy footpathapp.com.

Bike racks and tire pump at the Staten Island end of the bridge.

I picked a very pleasant day for this walk, with low humidity, a refreshing breeze, and high temperature of 26C (79F). The Bayonne Bridge, which opened in 1931, was the longest steel arch span in the world at the time of its construction and remained so for many years. It spans the narrow Kill van Kull that links Newark Bay and the huge container terminals at Port Elizabeth and Port Newark to New York Harbor. With the addition of a new, larger set of locks at the Panama Canal, “post-Panamax” container ships, those larger than could be accommodated by the original Panama Canal locks, could reach the Port of New York and New Jersey but for insufficient vertical clearance at the Bayonne Bridge. In recent years the roadway was raised some 50 feet (16 meters) to allow greater vertical clearance, the work being completed in 2019. The original steel arch was left intact but the roadway, being suspended from the arch on cables, was raised up. A new, much wider bike and foot path was built on the east side of the bridge, replacing the old path on the west side. For a nice, succinct history of this bridge go to https://www.panynj.gov/bridges-tunnels/en/bayonne-bridge/history.html.

I had biked across the bridge twice in the early 1990s, both times from Bayonne to Staten Island. This was my first time crossing on foot and going in the opposite direction. I don’t recall ever driving over the bridge.

The start of this walk was in the modest Elm Park neighborhood on Staten Island’s north shore, a microcosm of a much more diverse place than Staten Island is often thought to be. With the roadway being raised the ascent was steep but not too tiring. Along the way were interpretive posters about the waterway, the economy of the area, the construction of the bridge, and the ecology of the area. Not being in a hurry, I took time to read each of them. Three examples are in the following images.

The bridge itself is impressive and the views from the bridge were remarkable.

From mid-span on the bridge: Bayonne at left, Staten Island at right, the towers of Manhattan and Brooklyn in the distance.

Bayonne Bridge at mid-span.

Beyond the bridge, the Port Newark container terminal.

The end point was a short walk from the north end of the Bayonne Bridge, the southernmost point on New Jersey Transit’s Hudson-Bergen Light Rail, the 8 Street station. This was once a terminus for passenger trains on the Central Railroad of New Jersey. A handsome station building recalls the old, long since demolished Jersey Central station. I took the light rail to Exchange Place in Jersey City where I transferred to the PATH train to the World Trade Center, then to the subway for the trip home.

8 Street station, Hudson-Bergen Light Rail.

This was a fine walk, a long time in the works. I’m glad I picked a picture-perfect day for it. It was good to get farther than usual from the tourist trail, to see an engineering marvel adapted to changing times and made inviting for bicyclists and pedestrians. The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey did a nice job with this. You can see the detailed route of this walk at https://footpathapp.com/routes/8c1fab62-fa12-4d1e-9495-5aa544ab0ccc.

Map of this walk, reading from bottom to top.

To the Henry Hudson Bridge and Beyond

Henry Hudson Bridge in background.

WHERE: Inwood neighborhood of Manhattan, the Henry Hudson Bridge, and the Spuyten Duyvil and Kingsbridge neighborhoods of the Bronx.

START: Dyckman Street subway station (1 train, partially accessible)

FINISH: 238 Street subway station (1 train)

DISTANCE: 3.5 miles (5.6 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl and Keith Williams. Video and voice-over by Keith Williams. Maps courtesy Google Maps.

Route of this walk, reading from bottom to top.

Profile of this walk, reading from left to right.

The Henry Hudson Bridge is a high arch span over the Harlem River, just east of where it meets the Hudson River. There’s a walkway on the west side of the lower level of the bridge, accessible by local streets on the Bronx side and by a steep path through Inwood Hill Park on the Manhattan side. I hadn’t walked across the bridge in more than 25 years and wanted to do so again, in part to prove I could climb that slope on the Manhattan side (highlighted in red on the accompanying map).

On this low-humidity day I was joined by my friend Keith and his friend Cat. We set out from the Dyckman Street station of the 1 train. This station, dating from 1906, emerges from the deepest tunnel in the subway system. There is an elevator to the downtown platform; an elevator to the uptown platform is under construction. Dyckman Street is a busy commercial thoroughfare in a crazy-quilt multi-ethnic neighborhood; we walked northwest toward the Hudson River and Inwood Hill Park. There we walked along the river toward the footbridge over Amtrak’s Empire Line and the path to the Henry Hudson Bridge, enjoying a refreshing breeze along the river.

View of the Hudson River and the New Jersey Palisades from the Inwood Hill Park trail.

Footbridge over the Amtrak line, 46 steps up.

The footpath to the bridge continues from the east end of the footbridge over the Amtrak line. This is the route Amtrak uses for trains between New York and Albany, part of one of the most scenic train rides in America, along the Hudson River. The footbridge has 46 steps and is in good condition. At the east end of the footbridge we were greeted by a gentleman, older than I, who said he had recently walked from Kappock Street, near the Bronx end of the bridge, to Houston Street in Manhattan, about 13 miles (21 kilometers). Outstanding!

The footpath to the bridge is in very good condition and is well-shaded but it is steep. Steep hills are more difficult for me than stairs. I walked with care and was glad I had company for this part of the walk in particular. I was confident I could make it all the way to the bridge footpath and I did, feeling a nice sense of accomplishment at the top.

In the words of Yogi Berra, when you see a fork in the road, take it. The path to the right leads to the bridge; the path to the left leads under the bridge and to the east side of Inwood Hill Park.

The summit! The south end of the Henry Hudson Bridge.

View from the Henry Hudson Bridge of Amtrak’s Spuyten Duyvil drawbridge, the Hudson River, and the New Jersey Palisades. Compare with the previous image taken from river level. At mid-span the lower level of the bridge is 135 feet above mean high water.

The bridge footpath ends with 8 steps down to the frontage (service) road of the Henry Hudson Parkway. From there we went to nearby Henry Hudson Park, the centerpiece of which is a classical column that is a memorial to the navigator Henry Hudson. From urban archive.org:

During the Hudson-Fulton Celebration of 1909 (commemorating the 300th anniversary of Hudson's arrival and the centennial of Fulton's steamboat) a plan was developed to honor Hudson with a memorial. Land was donated, funds were amassed, architects Babb, Cook and Welch designed a 100-foot-high Doric column, and sculptor Karl Bitter began to model his statue of Hudson. The column was erected in 1912 but the project stalled in 1915 with low funds and the death of Bitter.

In 1935, Parks Commissioner Robert Moses revived the monument plans as part of his Henry Hudson Bridge and Park project. Karl H. Gruppe, one of Bitter's students, created the statue which was finally placed on top of the 25-year-old column and dedicated in January of 1938.

History has been rightly unkind to Robert Moses (1889 - 1981), New York’s “master builder,” but we all walk this earth leaving a mixed legacy. This was one of his good works.