Staten Island Ramble #1

WHERE: Just west of the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge, Staten Island

START: Grasmere station, Staten Island Railway

FINISH: Bay Street and Hylan Boulevard, then S51 bus to St. George Ferry Terminal

DISTANCE: 2.4 miles (3.9 kilometers)

Photographs by Michael Cairl and Jordan Centeno as noted. Maps courtesy of Google Maps.

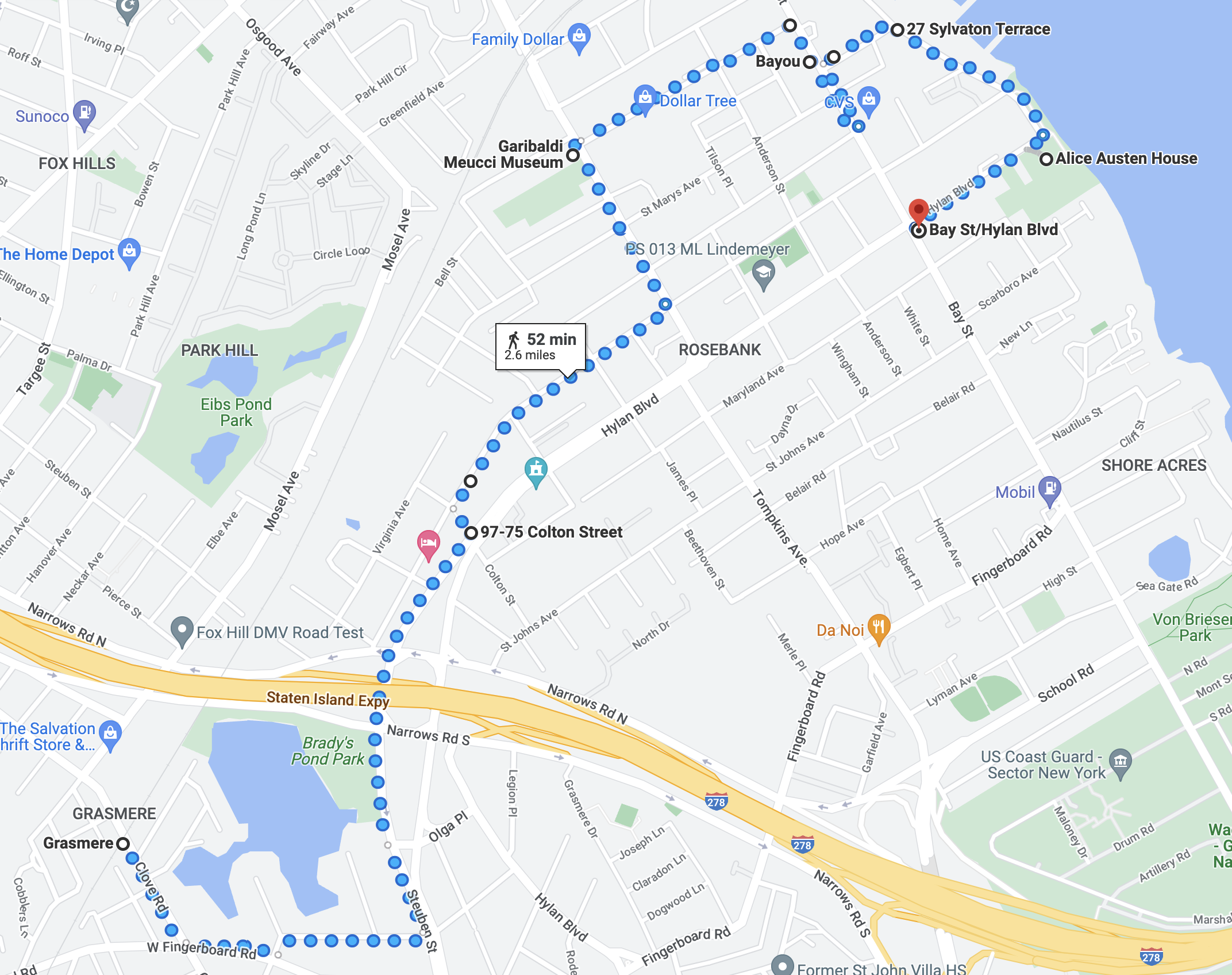

Route of this walk, reading from left to right.

The impetus for this walk was tackling my first stair street on Staten Island, Colton Street in the Rosebank neighborhood. See the post “Colton Street (Staten Island) on The Stair Streets of New York City page. But I was also able to visit two small museums in the area: the Garibaldi-Meucci Museum and the Alice Austen House. My friends Jordan Centeno and Matt Summers joined me on the walk.

We started by taking the Staten Island Railway from the St. George Ferry Terminal to Grasmere station. Grasmere is a quiet suburban neighborhood with sidewalks that are not always wide or even continuous. It reminded me of some of the leafier neighborhoods of eastern Queens.

Grasmere street scene: Windermere Road. Photograph by Michael Cairl.

From Grasmere station it was a more or less steady (but not steep) climb to past the Staten Island Expressway (Interstate 278), then a slight downhill to the Colton Street stairs. We descended the stairs to Clifton Avenue, then through a residential area to the commercial strip of Tompkins Avenue, then to the Garibaldi-Meucci Museum.

Why are there three crucifixes iin the parking lot of St. Joseph’s School? To let wayward whelps know the fate that might befall them if they fell afoul of one of their teachers? Photograph by Michael Cairl.

The Garibaldi-Meucci Museum on Tompkins Avenue. Photograph by Michael Cairl.

Michael and Matt goofing it up at the fence in front of the museum, before realizing the entrance was on Chestnut Avenue. Photograph by Jordan Centeno.

Historical marker outside the Garibaldi-Meucci Museum. Photograph by Michael Cairl.

Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807 - 1882) was a leading figure in the creation of a unified Italy from a collection of kingdoms and the Papal States. Unification was completed in 1870 when the Pope lost control of Rome and its surrounding region of Lazio. As a young adult Garibaldi entered the merchant marine and led rebellions in Brazil and Uruguay before returning to Italy to participate in the revolutions of 1848. He escaped with his life and sailed to New York to buy a merchant ship. This attempt failed and he moved in with his friend Antonio Meucci (1808 - 1889) on Staten Island, staying for several months in 1850 - 1851. Meucci was an inventor who deserves more fame than he got. Garibaldi returned to Italy and led an army of revolutionaries from Sicily through southern Italy.

The museum was Meucci’s house. It is well worth the $10 price of admission. There are numerous pictures and artifacts, and the docent gave an excellent discussion of both Garibaldi and Meucci. Find out more at https://www.garibaldimeuccimuseum.com/ but go visit. There is far more to learn about both men than can be told here.

A few minutes’ walk from the Garibaldi-Meucci Museum, on Bay Street, is Bayou Restaurant, chock-full of New Orleans stuff. They served us a delicious lunch. I had not been there in almost 20 years, when I was the project manager for the installation of a new signal system on the Staten Island Railway. I was glad they’re still alive, kicking, and serving good food. From there we walked down to the waterfront and on to the Alice Austen House.

Staten Island used to have a busy working waterfront, with shipbuilding and ship repair on the North Shore - some of which still exists - and docks and warehousing along the Narrows. When the U.S. Navy’s four battleships were reactivated in the 1980s, one of them, the Iowa, was based at Stapleton, not far from where we were. Some of the structures on the waterfront are active and some are derelict.

Scene at Sylvaton Terrace and Edgewater Street. Photograph by Michael Cairl.

Walking south on Edgewater Street toward the Alice Austen House, we came upon a waterfront promenade named for a local soldier killed in the Vietnam War, Matthew Buono, and sweeping views of New York Harbor.

Looking from the Matthew Buono memorial toward Brooklyn (top) and the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge (bottom). Photographs by Michael Cairl.

Alice Austen (1866 - 1952) was a photographer and native Staten Islander, not just a pioneering female photographer but a pioneering photographer and pioneering woman. Her home, Clear Comfort, was built in 1690 as a one-room Dutch farmhouse. In 1844 it was purchased by John Haggerty Austen, Alice Austen’s grandfather. It sits upon a slight, well-shaded rise above the Narrows, a beautiful spot now to visit and once to have lived. Austen photographed streetscapes, landscapes, scenes of the harbor, and ordinary working people. One can draw a line from her work to that of later photographers such as Berenice Abbott (1898 - 1991) and Helen Leavitt (1913 - 2009). To this longtime amateur photographer, Austen’s eye and sensitivity were remarkable. I could have spent hours going through the library of her prints, and I will go back specifically to do so.

Parlor in the 1844 addition to the house. Photograph by Michael Cairl.

Images of the Quarantine Station on Hoffman and Swinburne Islands, man-made islands from the 19th Century to seaward of the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge. Photograph by Michael Cairl.

About Austen, from the website https://aliceausten.org:

Austen was independently wealthy for most of her life and has widely been considered an amateur photographer because she did not make her living from photography. However, in addition to completing a paid assignment documenting the people and conditions of immigrant quarantine stations in New York during the 1890s, Austen copyrighted, exhibited and published her work.

Alice Austen’s life and relationships with other women are crucial to an understanding of her work. Until very recently many interpretations of Austen’s work overlooked her intimate relationships. What is especially significant about Austen’s photographs is that they provide rare documentation of intimate relationships between Victorian women. Her non-traditional lifestyle and that of her friends, although intended for private viewing, is the subject of some of her most critically acclaimed photographs. Austen would spend 56 years in a devoted loving relationship with Gertrude Tate, 30 years of which were spent living together in her home which is now the site of the Alice Austen House Museum and a nationally designated site of LGBTQ history.

Austen’s wealth was lost in the stock market crash of 1929 and she and Tate were finally evicted from their beloved home in 1945. Tate and Austen were separated by family rejection of their relationship and poverty. Austen was moved to the Staten Island Farm Colony where Tate would visit her weekly. In 1951 Austen’s photographs were rediscovered by historian Oliver Jensen and money was raised by the publication of her photographs to place Austen in private nursing home care. On June 9, 1952 Austen passed away. The final wishes of Austen and Tate to be buried together were denied by their families.

One of the images above is about the quarantine station on Hoffman and Swinburne Islands. A quick sidebar on these, from The Other Islands of New York City: A History and Guide, Second Edition by Sharon Seitz and Stuart Miller (The Countryman Press, 2001):

Staten Islanders had had enough. In 1858, after more than fifty years as New York’s dumping ground for people with deadly, contagious diseases - yellow fever, typhus, cholera, and smallpox - infuriated mobs burned the New York Quarantine Hospital to the ground. In the face of this unsurpassed expression of NIMBY-ism, the government was forced to create two artificial islands, Hoffman and Swinburne, to house the ill.

These islands, to seaward of the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge, are now part of the Gateway National Recreation Area and are home to migratory birds. For years in the 1970s, the Cunard liner Caronia was abandoned, at anchor off Hoffman Island, a ghostly presence.

Profile of this walk, readiing from left to right.

This walk was yet more proof of the fascinating things to be found in this city when one ventures beyond the well-trod tourist trail. It was a good walk with fascinating places visited, a good stair street, a fine lunch, all with good company. Onward!